* Late in World War II, the Fairchild Aircraft Company developed a pioneering tactical transport, the twin-engine, twin-boom "C-82 Packet", which led to the "C-119" Boxcar. The Boxcar was the US Air Force's standard tactical transport during the early Cold War; it lingered in service into the Vietnam War, a number of them serving as "AC-119" gunships. Along with the C-119, Fairchild also built another tactical transport, the "C-123 Provider", which was a mainstay of the US effort in Vietnam. This document provides a history and description of the C-119 and C-123. A list of illustration details is provided at the end.

* Early in World War II, the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) issued a requirement for an optimized military cargo transport -- the service's cargo aircraft at the time, like the Douglas C-47 Dakota, having been derived from civilian airliners, and leaving something to be desired as military cargolift machines. The new aircraft would not only be useful as a cargo carrier, but also as a troop / paratroop transport, as well as for medical evacuation and glider towing.

The Fairchild Company responded with a design for the "Model F-78". Following examination of the design proposal and a mockup in 1942, the USAAF awarded Fairchild a contract for a single prototype, to be designated "XC-82". The XC-82 performed its initial flight on 10 September 1944. The original specification had envisioned an aircraft made of non-strategic materials, such as steel and wood -- but changes in specification meant it ended up being an all-metal aircraft, made primarily of aircraft aluminum. Production orders followed for the "C-82A Packet" -- the name being derived from the small "packet" merchantmen of the age of sail.

The C-82A was of twin-boom configuration, with a Pratt & Whitney (P&W) R-2800-34 14-cylinder two-row air-cooled radial engine, providing 1,565 kW (2,100 HP), at the front of each boom, driving three-bladed variable-pitch propellers. The tailfins at the end of each boom were joined by a tailplane with a one-piece elevator. The aircraft had tricycle landing gear, all assemblies having single wheels, the nose gear retracting upward, and the main gear retracting forward into the engine booms.

There were clamshell doors on the rear, with inward-opening paratroop doors inset in each clamshell door; there was also a passenger door forward, on the left side of the fuselage. A truck could be backed up to the rear of the cargo bay without obstruction. The clamshell doors could be removed for parachute dropping.

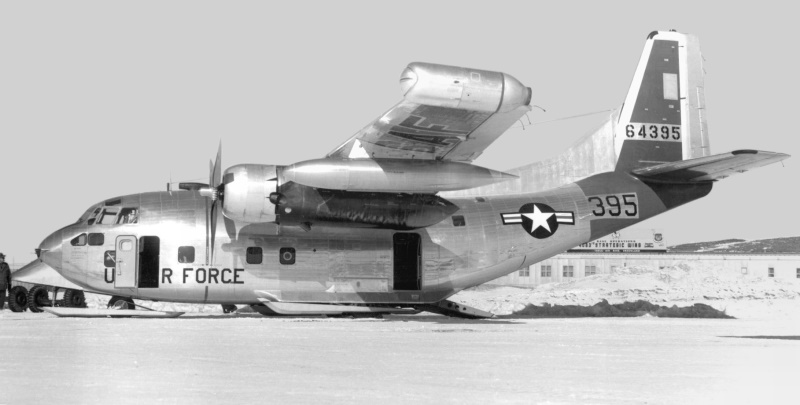

Large quantities of C-82As were ordered, but production was cut back with the end of the war. A total of 220 C-82As was built at the Fairchild factory in Hagerstown, Maryland, with deliveries from 1945 into 1948 -- by which time the USAAF had become a separate service, the US Air Force (USAF). Three similar "C-82N" machines were built by North American Aviation early on, but production at North American was canceled. In 1948, at least one C-82A was fitted with tracked landing gear, for rough-field operation, and redesignated "EC-82A". There were various experiments with using tracked landing gear for aircraft in that time period, and none of them worked out; there may have been more EC-82A conversions, but it just wasn't a good idea.

The C-82A never saw any combat service, though it did fly cargoes into Berlin during the Berlin Airlift in 1948:1949 -- primarily bringing in disassembled vehicles. Four were given specialized modifications for the airlift and redesignated "JC-82A". Some number of Packets, sources give 18 to 37, were modified for search and rescue (SAR) operations and redesignated "SC-82A".

Following service retirement, a number of C-82As were sold to civil operators in the US, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico, the last going out of service in the 1980s. The Stewart-Davis company performed some custom updates of C-82As -- including "Jet-Packet" mods, involving a Westinghouse J30 or J34 turbojet, or two J30 turbojets, mounted on top of the aircraft to provide boost power.

BACK_TO_TOP* The C-82A proved to have a number of limitations in service, the worst being that it was underpowered; it seems it was also not very robust, prone to dangerous structural failures. In 1947, a C-82A was converted to "XC-82B" configuration, with substantially more powerful P&W R-4360-20 28-cylinder four-row air-cooled Wasp Major radials, providing 1,975 kW (2,650 HP) each. That experiment going well, the same aircraft was substantially rebuilt, as the "XC-119A" -- the most prominent change being shifting the location of the cockpit from on top of the forward fuselage to flush in the nose, giving the aircrew a better view of the runway. The fuselage was widened as well.

The XC-119A led to the production "C-119B", with its initial flight in November 1947, and service deliveries the next year; it would become popularly known as the "Flying Boxcar", though crew nicknames included the "Flying Spam Can" or "Dollar-Nineteen". Officially, it was still a "Packet" -- indeed, it appears the C-82A may have casually been called the "Flying Boxcar" as well.

The general configuration of the C-119B was effectively the same as the C-82A, the major differences between the two types being the more powerful engines and relocated cockpit of the C-119B. The C-119B also differed in having a fuselage widened by 36 centimeters (14 inches); twin-wheel main landing gear, to handle higher take-off weights; and four-bladed Hamilton Standard paddle props. Incidentally, the XC-119A remained in trials use, being designated "EC-119A" -- the "E" standing for "exempt", meaning exempt from regular service.

55 C-119Bs were built for the Air Force, plus eight for the US Navy / Marine Corps, as the "R4Q-1". Production then moved on to the "C-119C" -- much the same, except that the extensions of the tailplane outside the tailfins were removed, and long forward fin fillets added to the tailfins. The fin fillets were presumably to improve yaw stability and help with engine-out handling, and possibly for structural reinforcement of the tailbooms. 304 C-119Cs were built for the Air Force, with 31 more made for the US Navy / Marine Corps, also with the designation of "R4Q-1".

One C-119C was used for trials of a tandem landing gear scheme, being redesignated "EC-119C". There are photos of a C-119 with the tailplane extensions and the fin fillets; it seems that some C-119Bs were upgraded with the fin fillets, and possibly other features of later variants.

Concepts for a "C-119D" and "C-119E" didn't pan out, so the next production variant was the "C-119F", the main change being a switch from Pratt & Whitney Wasp Major engines to two-row, 18-cylinder Wright R-3350-85 Turbo Compound engines, providing 1,860 kW (2,500 HP) each. Other changes included the addition of ventral fins under the tailfins, and twin-wheel nose gear -- the single big wheel of earlier variants tended to shimmy. The Turbo Compounds had triple turbochargers to provide boost power; they were actually called "power recovery turbines", since they fed power back into the driveshaft through hydraulic couplers, instead of driving air back into the engine intake.

Following conversion of a C-119C with the Turbo Compound engines as the "YC-119F", 245 production C-119Fs were built, including 71 produced by Ford -- an exercise in second-sourcing that apparently did not go well. 58 C-119Fs were also built for the Navy / Marines under the designation of "R4Q-2". Many C-119Cs were brought up to a "C-119CF" standard, retaining the engines of the C-119C but adding the other features, like the twin-wheel nose gear. In 1962, when the Pentagon went to a common designation scheme, the R4Q-2s reverted to the "C-119F" designation.

The last production version was the definitive "C-119G", which was the same as the C-119F, but with four-bladed Aeroproduct props replacing the Hamilton Standard props. The Hamilton Standard props had difficulties, being hollow and inclined to "delamination", leading to disintegration. Unfortunately, the Aeroproduct props were no great improvement, being prone to uncontrolled prop runaway.

___________________________________________________________________

FAIRCHILD C-119G BOXCAR:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

33.3 meters (109 feet 3 inches)

wing area:

134.4 sq_meters (1,447 sq_feet)

length:

26.37 meters (86 feet 6 inches)

height:

8 meters (26 feet 3 inches)

empty weight:

18,135 kilograms (39,980 pounds)

MTO weight:

33,750 kilograms (74,400 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

475 KPH (295 MPH / 255X KT)

cruise speed:

320 KPH (200 MPH / 175 KT)

service ceiling:

7,300 meters (24,000 feet)

range:

3,670 kilometers (2,280 MI / 1,980 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

484 C-119Gs were built, with early models of the Boxcar generally brought up to C-119G standard. That gave total production of 224 C-82s and 1,185 C-119s, variants including:

The Flying Boxcar saw plenty of service in the Korean War, with an initial contingent of four machines sent to the Far East in July 1950 -- only weeks after the outbreak of the conflict -- for evaluation, with the C-119 arriving in force in September. In December, after the Chinese had intervened and sent over-extended United Nations forces falling back south, C-119s performed airdrops in support of the troops -- one of the most significant being the drop of a transportable bridge to replace one that the Chinese had destroyed. The bridge was in eight sections, dropped in eight sorties, with two parachutes used for each section.

From 1953, C-119s saw service in French Indochina, with Boxcars loaned to the French, operating in French markings with CIA pilots, along with French crews. They performed airdrops in the futile attempt to maintain the French garrison in the besieged base at Dien Bien Phu. At least one was shot down during the effort.

New-build C-119s were supplied to Belgium, Canada, India, and Italy. Indian use of the C-119 was somewhat unusual, since the Indians rarely obtained US gear. Indian Boxcars were fitted with a Bristol Orpheus turbojet in a dorsal mount, built by the Steward-Davis firm of the US, for boost power under "hot and high" flight conditions. They participated in the Sino-Indian War of 1962. Hand-me-down machines were eventually supplied to Brazil, Ethiopia, France, Greece, Jordan, Morocco, Norway, South Vietnam, Spain, and Taiwan.

BACK_TO_TOP* The C-119 was a standard USAF tactical transport through the 1950s and into the early 1960s, seeing service all over the world. Several improved variants were introduced through modification programs:

Five C-119Js were modified to a medical evacuation standard and redesignated "MC-119J", while the Italians modified three to a "VC-119J" VIP transport standard. However, the C-119J achieved greater distinction with four "EC-119J" conversions, which snagged the parachutes of film capsules or "buckets" returned by spy satellites from orbit.

The scheme had originally been devised in the mid-1950s to recover payloads from reconnaissance balloons sent over the USSR; that exercise was a bust, but when CORONA spy satellites started flying at the end of the decade, the aerial-recovery scheme came in handy. The first recovery of a CORONA film bucket by an C-119J was on 19 August 1960. Some sources hint the C-119J's new rear door configuration was specifically designed with the aerial recovery role in mind. The EC-119Js were later replaced by the Lockheed Hercules, with machines configured for satellite recovery designated as "JC-130B".

* The Boxcar remained in firstline USAF service to 1962, serving all over the world. After its general replacement by the Lockheed C-130 Hercules cargolifter, it was revived for a "second life" in Southeast Asia. The story began with the modification of old Douglas C-47 transports into "AC-47 Spooky" gunship, fitted with triple 7.62-millimeter (0.30-caliber) Gatling Miniguns firing out the side; an AC-47 would perform a banking turn in a circle on a target, firing into the center of the circle.

The AC-47 proving successful, the Air Force wanted to field the much more sophisticated and potent "AC-130 Spectre" gunship, based on the C-130 Hercules -- but obtaining enough C-130s proved difficult. There were plenty of C-119s sitting in mothballs, however, and so 26 C-119Gs were pulled out of storage, to be fitted with four side-firing Miniguns, armor plating, a searchlight, flare launcher, and an infrared imager.

The result was the "AC-119G Shadow", which proved successful in combat after introduction to the war theater in 1968. 26 more C-119Gs were then updated to "AC-119K Stinger" configuration, which featured the underwing J85 turbojets of the C-119K, plus twin side-firing 20-millimeter Gatling cannon along with the four Miniguns, as well as more sophisticated combat avionics. Although not the equal of the AC-130, the C-119 gunships were used with good effect in close air support missions in South Vietnam, as well as interdiction missions against trucks and supplies along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. They were handed on to the South Vietnamese in 1973, when US forces pulled out.

The C-119 lingered in Air Force Reserve / National Guard service to 1974. A number ended up in civilian hands, in some instances being fitted with the Steward-Davis "Jet Pack" modification, with a single J34 turbojet mounted on top. A number of civilian C-119s were used in the "air tanker" role to fight forest fires, finally being retired from that role in 1987. A number of C-119s survive as museum displays; it doesn't appear any are still flying.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Fairchild C-123 Provider was actually designed by the Chase Aircraft Company of New York, which was founded in 1943, with a focus on development of cargo gliders for the US Army Air Forces. The initial result of this effort were the "XCG-14" and "XCG-14A", of wooden construction, with 16 and 24 seats respectively. Prototype flights were conducted in 1945; they didn't go into production, but they provided a basis for further work on all-metal gliders.

The first of these, the "XCG-18A", with 32 seats, took to the air for the first time in December 1947. It featured an upswept rear fuselage, which would acquire a hydraulically-operated loading ramp -- and become a standard configuration feature for modern cargolifters. In the spring of 1948, the Air Force ordered a batch of five "YG-18A" service evaluation machines, with a contract awarded in parallel for two similar but enlarged "XCG-20" gliders.

However, the effort then took a zigzag. Combat gliders had always been dubious, being notoriously unsafe. In the postwar period, new technologies emerged to challenge the glider, including schemes for paradropping heavy payloads, and tactical transports designed to operate off rough strips. Although the USAF saw no further need for combat gliders -- the XCG-20s were the last to be built in the US -- the Chase gliders seemed like a good basis for tactical transports.

One YG-18A was accordingly fitted with twin P&W R-2000 Twin Wasp radials, performing its initial flight in that configuration in November 1948, with the revised aircraft being designated "YC-122". In 1949, nine "YC-122C" evaluation machines were ordered, being powered by Wright R-1820 9-cylinder single-row Cyclone engines, these machines being operated by the Air Force from 1951 to 1954, and then scrapped. The YC-122s had some unusual features, such as retractable nose gear but fixed main gear, with all fuel in jettisonable self-sealing tanks in the engine nacelles.

The two XCG-20s never flew as gliders. One was fitted with twin P&W R-2800-23 engines, providing 1,640 kW (2,200 HP) each, to become the "XC-123", to perform its first flight on 14 October 1949. The other, the "XC-123A", was fitted with four GE J47-GE-11 turbojets in pairs -- the engine assembly being much the same as it was for the Boeing B-47 Stratojet bomber -- to perform its first flight on 21 April 1951.

The jet-powered XC-123 was a non-starter, a strange mismatch -- it was almost as if it were done just to see if it could be -- and disappeared with little trace; but the piston-powered XC-123 was promising. Chase was given a contract in 1952 to built five pre-production "C-123B" aircraft, the aircraft being built and flown in 1953. Chase was bought out by Kaiser in that year, with the company awarded a contract by the USAF for 300 C-123B machines -- but Kaiser ran into problems arranging production, and Fairchild ended up obtaining a contract in October 1953 to build the C-123B. The first Fairchild C-123B performed its initial flight on 1 September 1954, with Fairchild producing 302 of them, including a static-test airframe.

The C-123B was of all-metal construction, with a high wing, high tail, and retractable tricycle landing gear -- the nose gear with dual wheels, the main gear with single wheels, all gear retracting into the fuselage. Flight control surfaces were of conventional arrangement -- large flaps, ailerons, elevators, rudder -- the only peculiarity being a very large forward tailfin fillet. An external fuel tank could be fitted outboard under each wing. Crew included pilot, copilot, and a loadmaster. It could carry 62 troops, or be configured as a 50-litter medevac transport. There were inward-opening jump doors on both sides of the rear fuselage, plus a forward-opening crew door on the front left fuselage.

___________________________________________________________________

FAIRCHILD C-123B PROVIDER:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

33.53 meters (110 feet)

wing area:

113.6 sq_meters (1,223 sq_feet)

length:

23.09 meters (75 feet 9 inches)

height:

10.39 meters (34 feet 1 inch)

empty weight:

13,560 kilograms (29,900 pounds)

MTO weight:

27,215 kilograms (60,000 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

405 KPH (250 MPH / 220 KT)

service ceiling:

7,315 feet (24,000 feet)

range (with 7,260-kilogram / 16,000-pound payload):

2,155 kilometers (1,340 MI / 1,165 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

Among the 302 C-123Bs built, eight were supplied to the US Coast Guard as "HC-123Bs", for logistical transport, with search & rescue as a secondary mission; they were fitted with an AN/APN-158 search radar in a nose radome. New production also included 6 aircraft for Saudi Arabia -- one apparently being passed on to Egypt -- and 18 for Venezuela.

BACK_TO_TOP* After entering formal service in 1955, the C-123 became the standard USAF tactical transport. Several dozen were also used by the Strategic Air Command to support bases in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. The USAF flight demonstration team, the Thunderbirds, used the C-123 for logistics support, this aircraft also being used to haul the presidential limousine on occasion.

Ten C-123Bs were fitted with two Fairchild J44 turbojets, with about 4.45 kN (450 kgp / 1,000 lbf) thrust each, one mounted on each wingtip; they were also fitted with neat retractable ski landing gear, to be given the new designation of "C-123J", and used for service in Arctic regions. The US Federal Aviation Administration also used two Providers similarly fitted with Continental J69 turbojets on the wingtips, the J69 being derived from the French Turbomeca Marbore turbojet. These two machines were used in Arctic regions as well; it is not clear if they had any special designation.

After test of a "YC-123H" prototype in 1962, focused on improving the C-123 for service in Southeast Asia, 180 C-123Bs were updated to "C-123K" standard, the primary change being fit of a GE J85 turbojet under each wing for take-off boost power, permitting them to operate at higher weights and off of shorter runways. The intakes of the nacelles for the J85s featured doors that could be closed to reduce drag when the jet engines were shut down. The C-123Ks also featured larger main-wheel tires and anti-skid brakes; the YC-123H had been fitted with revised main landing with a wider track, but that was judged more bother than it was worth for the C-123Ks.

There were a number of one-off mods of the C-123:

Stroukoff considered a turboprop conversion of the C-123, but it never happened. The Thais investigated updating their fleet of C-123s with turboprop propulsion, with a single "C-123T" conversion performed by the Mancro Aircraft Company, powered by Allison T56-A-7 turboprops. The C-123T also had new "wet" wings, an auxiliary power unit turbine, and other tweaks. The Thais ran out of money, and there were no more conversions. There was talk after that of converting mothballed C-123s with T56 turboprops, but nothing came of the matter.

* The C-123 provided extensive service in the Vietnam War as a tactical transport, with C-123Ks distinguishing themselves in supply of the besieged Marine base at Khe Sahn in 1968, flying 179 sorties in support of the defense. However, they would be better remembered as the delivery system for herbicides at war, in which at least three C-123Bs and 34 C-123Ks were fitted with sprayer gear, to be redesignated "UC-123B" and "UC-123K" respectively.

The sprayers flew RANCH HAND missions, to disperse defoliant over jungle areas, reducing them to lifeless areas in which Viet Cong insurgents couldn't hide; and also performed TRAIL DUST missions to destroy crops that would feed the Viet Cong. The exercise would prove controversial, with the defoliant -- known as "Agent Orange" -- blamed for cancers among the aircrews, though a link was never conclusively proven.

The defoliant missions were performed at very low level, with the UC-123s operating in groups of three or four. At that altitude, they often came under small-arms fire, returning to base pocked with bullet holes. The missions were often covered by a strike fighter, typically a North American F-100 Super Sabre, carrying cluster bombs or other munitions to pound Viet Cong who fired on the UC-123s.

The C-123 served other special roles during the war in Southeast Asia:

In 1965, as something of an operational experiment, two C-123K aircraft were modified by E-Systems of Greenville, Texas, to "self-contained night attack capability" configuration under Project BLACK SPOT. They featured a suite of night-combat sensors, including an X-band ground-mapping radar in an extended nose, plus a turret under the nose with a forward-looking infrared (FLIR) imager, a low light level TV (LLTV) imager, and a laser rangefinder. They also had a Doppler radar altimeter and a missions system computer.

These BLACK SPOT aircraft were fitted with two bins in the cargo bay for stowing cluster bomblets, the bomblets being dispensed through a dozen doors in the belly of the aircraft. Depending on the type of bomblet, the BLACK SPOT Providers could carry from 2,664 to 6,372 bomblets. The bomblets could be dispersed in batches using a control panel in the cockpit, or collectively dumped in an emergency.

The BLACK SPOT machines were redesignated "NC-123K" in 1968, then "AC-123K" in 1969. They were operated out of South Korea for evaluation in the last half of 1968, helping to hunt down North Korean infiltrators, to be relocated to Vietnam late in that year, and then shifted to Thailand. They performed night patrols over the Ho Chi Minh trail over Laos and South Vietnam; they served for almost two years, scoring hundreds of kills on trucks and other targets, while receiving additional electronics upgrades in service. After their withdrawal from combat, they were returned to C-123K configuration.

* The CIA made good use of the C-123 in Southeast Asia, employing five for the agency's "Air America" front operation, performing transport runs into the hills of Vietnam and Laos. In the early 1960s, the CIA also set up a flight of five C-123Bs with the Republic of China (Taiwan) Air Force for covert operations, these machines being fitted with defensive countermeasures, and additional fuel in underwing tanks. They were officially flown by China Airline, Taiwan's national airline, out of Da Nang Air Base for covert missions into North Vietnam.

These Taiwanese C-123Bs were transferred from CIA to Air Force Special Operations Group (SOG) in 1964. In that same year, under Project DUCK HOOK, six more C-123Bs were converted to an enhanced covert operations configuration, not merely with defensive countermeasures, but also terrain-following radar. They flew out of Nha Trang Air Base, north of Cam Ranh Bay. They were given weather radar and a navigation receiver in 1966, to permit operations over the Ho Chi Minh trail; in 1968, they were updated to C-123K standard, with the wing-mounted turbojets, plus enhanced countermeasures systems, the designation being renamed HEAVY HOOK. The operation was deactivated from 1972.

* Following the end of the Vietnam War, surviving C-123s were passed on to the Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard. They were primarily used as tactical transports -- but the UC-123s went on spraying under the "Special Spray Flight", for the humanitarian mission, traveling far and wide to help suppress insect-borne diseases by spraying insecticides.

The C-123 was also used as "jump aircraft" for U.S. Army Airborne students located at Lawson Army Airfield, Fort Benning, Georgia in the late 1970s and early 1980s. This aircraft was used in conjunction with the Lockheed C-130 Hercules and Lockheed C-141 Starlifter.

The CIA continued to use the C-123 after the Vietnam War. Not much is known about their activities, but it is known one was shot down by an SA-7 Grail shoulder-launched missile on 5 October 1986, while carrying arms and ammunition in Nicaragua to supply Contra insurgents. Two of the crew were killed; a third parachuted to safety, to be captured and held prisoner until December of that year.

The final examples of the C-123 in active US military service were retired from the Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard in the early 1980s. Some airframes were transferred to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for test and evaluation programs, while others were transferred to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) for miscellaneous other programs. These aircraft were also retired by the end of the 1990s. A number of C-123s are on static display; it appears that at least one is still flying at airshows.

BACK_TO_TOP* A C-119B was experimentally converted to an unusual "modular" cargo aircraft, the "XC-120 Packplane", which performed its first flight in 1950. It retained the general C-119 configuration, but with substantial modifications -- most notably chopping off the lower part of the fuselage, to allow removable "pods" to be rolled in and attached. The inner wings were also raised to provide a dihedral and more height, while the main gear was modified to provide a second assembly with smaller dual wheels set forward, to take the place of nose gear.

The scissor-like arrangement of the gear assemblies allowed the airframe to jack itself up and lower itself again, useful for loading and unloading pods. A pod might be configured as a field hospital or a machine shop. Exactly what happened with the XC-120 in trials is unclear, but the project was abandoned in 1952, and that was the end of the matter. Possibly the idea simply didn't seem as useful in practice as it had seemed on paper. There have been other experiments with modular aircraft; they have not in general gone well.

* Some air enthusiasts find the Flying Boxcar quirky in appearance, but I'm perfectly comfortable with it myself -- since when I was little, I used to see them flying around my hometown of Spokane, Washington, all the time. It appears they were flying out of Fairchild AFB there, or possibly the ANG base at Geiger Field.

* There's not a lot of information available on the C-119 and C-123, and this document ended up being a scavenger hunt, starting with the Wikipedia article on the aircraft, and finding data from websites like THE AVIATION ZONE and others. I think this document is generally accurate, but only because I threw out any details I wasn't very sure of.

* Illustrations details:

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 jul 18 v1.0.1 / 01 may 20 / Review, update, & polish. v1.0.2 / 01 mar 22 / Review & polish. v1.0.3 / 01 feb 24 / Review & polish. (+)BACK_TO_TOP