* During World War II, the British government set up a "Brabazon committee" to consider requirements for airliners to come into service in the postwar period. The result was a dog's breakfast of airliners and cargo haulers, two of the more prominent in the batch being the turboprop Bristol "Britannia" and Vickers "Viscount", the Viscount proving a success story while the Britannia did not. This document provides a history and description of the Britannia and the Viscount -- as well as the one-off eccentric "Brabazon" airliner, and the Viscount's successor, the "Vanguard".

* Britain had a thriving aircraft industry before World War II, producing a wide range of military and civil aircraft in large numbers. With the beginning of the war, Britain was forced to focus on churning out military aircraft. Although the British military situation in 1940 and 1941 was desperate, the entry of the USA into the conflict gave encouragement that the war could be won.

To make best use of manufacturing resources, the British agreed that they would produce heavy bombers for their own use, while making use of American-made transport aircraft, which in practice largely meant the excellent Douglas C-47 / DC-3. British aeronautical authorities quickly realized that, once the shooting was over, America would be in a position to dominate the global commercial air transport market, with Britain left scrambling to catch up. Britain and the British Commonwealth would then be dependent on American transport aircraft.

In consequence, the British government set up a committee under Lord Brabazon of Tara to see what could be done to maintain British influence in the global transport market. The "Brabazon Committee" began meetings in early 1943, working with members of the state-owned airlines British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) and, later, British European Airways (BEA). The committee generated proposals for a new generation of British transport aircraft in the postwar period, providing general specifications for what started out as four different classes of aircraft:

In 1944, the British Ministry of Supply issued contracts for aircraft in these categories. The Type I became "Air Ministry Specification 2/44", with Bristol and Miles submitting proposals; the "Bristol Type 167" proposal was accepted, being cheekily named the "Brabazon", with two prototypes ordered. Construction of the first prototype began in October 1945, with the aircraft first taking to the air on 4 September 1949, with Bristol Chief Test Pilot Bill Pegg in the pilot's seat.

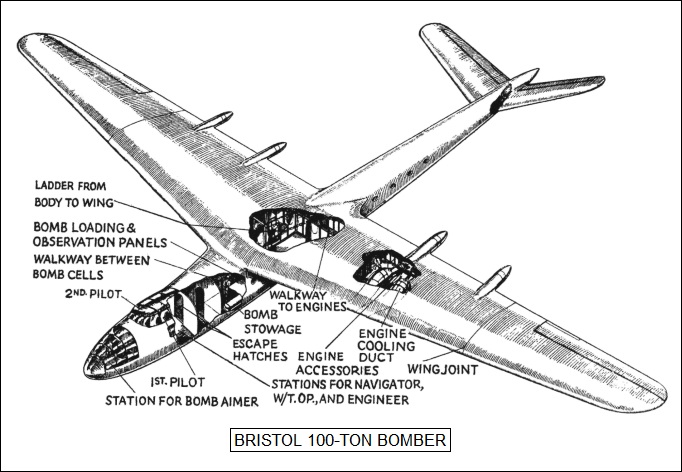

The Brabazon was derived from proposals for a "100-Ton Bomber" submitted to the Air Ministry in early 1943 from Bristol and other British aircraft companies. The requirement was for a very heavy long-range bomber, comparable to the American Convair B-36 of the immediate postwar period. The Bristol submission for the 100-Ton Bomber featured four pusher contra-rotating propellers, each driven by twin 18-cylinder air-cooled 18-cylinder two-row Bristol Centaurus radials. In early concepts, the aircraft featured top, bottom, and tail turrets, each with four 20-millimeter cannon, and an internal bomb-bay; defensive armament was later dropped, altitude being used for defense.

Britain never flew a 100-Ton Bomber, but Bristol used their design ideas as the basis for the Type 167. The Brabazon retained the basic propulsion scheme, though with the contraprops changed to a tractor configuration, at the front of the wing. Although the Brabazon was smaller than the 100-Ton Bomber, it was still a huge aircraft for the era, being a low-wing monoplane of all-metal construction with a cigar-like fuselage and tricycle landing gear. Its appearance suggested something out of a contemporary pulp science-fiction magazine.

___________________________________________________________________

BRISTOL BRABAZON:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

70.1 meters (230 feet)

wing area:

494 sq_meters (5,317 sq_feet)

length:

53.95 meters (177 feet)

height:

15.24 meters (50 feet)

empty weight:

65,815 kilograms (145,100 pounds)

MTO weight:

131,550 kilograms (290,000 pounds)

cruise speed:

400 KPH (250 MPH / 220 KT)

cruise altitude:

7,625 meters (25,000 feet)

range:

8,045 kilometers (5,000 MI / 4,350 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

The flight control surfaces were hydraulically boosted. Each Centaurus engine provided 1,860 kW (2,650 HP) and was canted 45 degrees from the forward, one canted left and one canted right, with a drive shaft feeding into the contraprop gearing system; each Rotol contraprop had three blades, There were large intakes in the fat wing in front of each engine. The steerable nose gear had dual wheels and retracted backward; each main gear had four wheels in a four-across configuration, in the form of twin duals, retracting forward in the wing between the inboard and outboard engine stations. The aircraft had spacious accommodations for a hundred passengers, with luxuries such as a cinema with a lounge and bar. The aircraft was pressurized and climate-conditioned.

Facilities at Bristol's Filton works and associated airport were hopelessly inadequate for one of the biggest aircraft built to that time; a huge assembly hall had to be built and the runway was quadrupled in length, requiring relocation of the inhabitants of a village. The giant airliner was demonstrated at the Farnborough Air Show in 1950 and the Paris Air Show in 1951, making an impression on the crowds -- but BOAC interest in the machine was fading out, and nobody else wanted it.

The program was canceled in July 1953 after the expenditure of millions of pounds by the government, the prototype being broken up for scrap. Work had been underway on a "Mark II" Brabazon that would have Proteus turboprop engines instead of the Centaurus radials, plus other refinements; the incomplete second prototype was broken up as well.

The Brabazon was doomed by an unrealistic business model, which projected that the primary customers for trans-Atlantic flights would be the very rich, the result being a "flying luxury liner" whose economics were hopeless. The postwar period saw a boom in airliner usage and a democratization of air travel, with air fares easily in reach of the middle class. It was also, in hindsight, simply too gimmicky to take very seriously. The Brabazon did prove a useful testbed for advanced aircraft technologies, and Bristol's improved works at Filton would prove useful for more successful aircraft.

BACK_TO_TOP* Although the Brabazon Type I aircraft proved a nonstarter, the Bristol company also obtained the contract for the Brabazon Type III MRE airliner. This effort would work out much better, if still not perfectly. Bristol generated proposals for the Type III in 1946, initially focusing on the Lockheed Constellation as the baseline aircraft, but BOAC wanted a new design. The Minister of Supply issued specification "C.2/47" in April 1947 covering the MRE aircraft, describing an airliner with 48 seats, powered either by Bristol Centaurus radial engines or Napier Nomad compound engines. Turboprop engines were also considered, though they were still an immature technology.

Full go-ahead for the Bristol "Model 175" was given in July 1948, with three prototypes ordered:

However, after more zigs and zags in requirements, when the first prototype of the Bristol "Britannia", as it was patriotically named, took to the air on 16 August 1952 -- with Bill Pegg again in the pilot's seat -- it was powered by Proteus 625 turboprops, providing 2,820 kW (3,780 HP) each, later updated to Proteus 705 engines, with 2,900 kW (3,900 HP), and had a nominal capacity of 75 seats. The decision to focus on the Proteus as the Britannia's powerplant was risky, since at the time turboprops were a largely unproven technology, but the high power-to-weight ratio of the turboprop relative to piston engines seemed worth the risk.

Alas, Proteus development was held up by difficulties, with BOAC waffling adding to the Britannica's woes. That wasn't the end of trouble from those two directions, either. The initial flight of the prototype, designated the "Britannia 101", had its difficulties, such as smoke filling up the cockpit and sticky main undercarriage, but it survived and the bugs were worked out. It was flying right enough to put on a demonstration at the Farnborough air show in September 1952, where observers commented on how quiet it was.

Unfortunately, the Britannia continued to be dogged by problems beyond its control. While the de Havilland Comet jetliner, being developed in parallel, had been praised as a world-beater when it took to the skies, several were mysteriously lost with all hands after it entered commercial service -- the problem turning out to be catastrophic loss of pressure when a window gave way. The problem was fixed, but the Comet would never really recover from the blow; it also made BOAC very skittish, with the Britannia forced to endure extensive tests for several years.

Matters were not improved when the second prototype was written off in December 1953 when Pegg had to force-land in the Severn estuary, one of the Proteus engines having caught fire; the first prototype also had a hair-raising departure from normal flight, due to a stuck flap, that led to its grounding for a time. The program did continue, with the first prototype being brought up to near production standard. Unfortunately, the Britannia continued to be dogged by engine problems and BOAC indecisiveness, and it wasn't until the end of 1955 that the first two "Model 102" production machines were handed over to BOAC for crew training, with the Britannia entering passenger service in February 1956. All 15, all built at Filton, had been accepted by BOAC by August 1956. The first prototype went on to be used in trials of various turboprops.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Britannia Model 102 provides a baseline for the series. In contrast to the pulp sci-fi lines of the Brabazon, the Britannia was a very clean and "unfunny" design. It was an all-metal low-wing aircraft of conventional arrangement, made mostly of aircraft aluminum, with some steel and a little titanium, and with tricycle landing gear. It was powered by four Proteus 705 turboprops, driving four-bladed de Havilland variable-pitch props with square tips. The engines had a fire extinguisher system; there was also a fire extinguisher system in the underfloor cargo holds. All fuel storage was in bag tanks in the wings; total fuel capacity of the Britannia 102 was 30,320 liters (6,670 Imperial gallons / 8,070 US gallons).

Control surface layout was conventional, each wing featuring wide-span double slotted flaps, in three segments since they were broken up by the engine nacelle, and an outboard aileron in two segments; with the tail assembly featuring elevators and a rudder, the tailfin being fitted with a forward fin fillet. The flaps were electrically actuated; the flight control surfaces were manually driven, but they used what were obscurely called "servo tabs" to minimize pilot effort.

Each of the flight control surfaces -- ailerons, elevators, rudder -- had a full-span tab running along its trailing edge, with the pilot changing the angle of a tab, which then changed the angle of its flight control surfaces. For example, to change the angle of the elevators downward, the pilot changed the angle of the elevator tabs upward. The elevators themselves were effectively free-hinging, except it seems for a bit of spring loading to normally maintain their neutral position. Airflow over the upraised tab pivoted the elevator down; if the elevators were to be raised, the tab would be lowered instead. A few of the servo tabs were also wired for use as trim tabs, their offset angle being set by rotating cockpit knobs.

The cockpit controls were of course wired so the pilot didn't have to concern himself with the counter-intuitive "backwards" action of the servo tabs. The leverage provided by the tabs meant the pilot didn't have to use very much muscle; but that meant the pilot no longer had much "feel" for the position of the flight control surfaces. In consequence, an "artificial feel" scheme was incorporated into the flight controls. Indications are that the servo tabs worked very well.

The wings were de-iced by engine bleed air, as were the engine intakes; the leading edges of the tailplane surfaces, prop assemblies, and the cockpit windshield were electrically de-iced. The steerable nose landing gear had twin wheels and retracted forward; each main gear assembly had four wheels, in a 2x2 bogey arrangement, and retracted backward into the inboard engine nacelles.

___________________________________________________________________

BRISTOL BRITTANIA 102:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

43.37 meters (142 feet 4 inches)

wing area:

192.9 sq_meters (2,075 sq_feet)

length:

34.75 meters (114 feet)

height:

11.17 meters (36 feet 8 inches)

empty weight:

35,645 kilograms (78,600 pounds)

MTO weight:

68,025 kilograms (150,000 pounds)

cruise speed:

550 KPH (340 MPH / 295 KT)

cruise altitude:

8,535 meters (28,000 feet)

range:

6,600 kilometers (4,100 MI / 3,565 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

Aircrew consisted of pilot, copilot, navigator, and radio operator, with an auxiliary seat for a fifth cockpit crewperson -- as well as flight attendants. Avionics were normal for the time, including radios, identification transponders, navigation and landing aids, and a nose radar. The fuselage was cylindrical, with a diameter of 3.66 meters (12 feet). There was six-across seating with a central aisle, with typical seating for 90 passengers. Of course, accommodations were pressurized and climate-conditioned. The cockpit, however, tended towards the frigid.

There was a row of large vertical-elliptical passenger windows on both sides of the fuselage. There were passenger doors fore and aft of the wing; for emergency exit, alternating windows could be jettisoned. There was an escape hatch on top behind the cockpit. Inflatable dinghies were stowed in the wings and in the passenger cabin for ditching at sea.

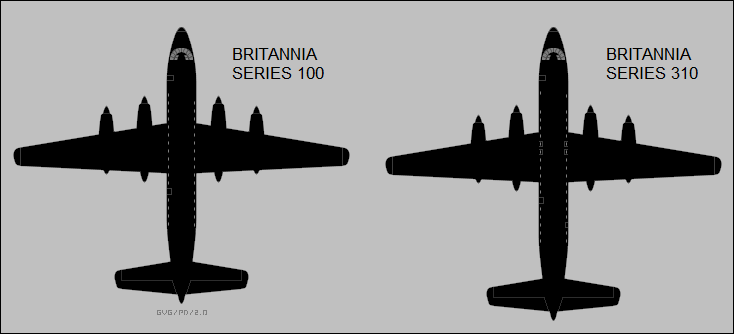

BACK_TO_TOP* While the Britannia 102s were being delivered, BOAC was also discussing a stretched derivative, which emerged as the "Britannia Series 300". It was extended by 3.12 meters (10 feet 3 inches), using plugs fore and aft of the wing, the forward plug being twice as long as the rear, giving a maximum passenger capacity of 99 seats.

The same passenger door arrangement was retained, but the emergency exits were rethought, it having been recognized that the idea of popping out alternating windows was impractical, since in most cases it implied excited and frantic passengers taking a fair drop to the pavement. Only two windows on each side of the fuselage, above the wing, were made jettisonable, while an emergency exit door was installed in the rear of the fuselage on the left side, with two more emergency exit doors matching the rear passenger door and emergency exit door on the right.

Unfortunately, introduction of the Series 300 was delayed because of problems with the Proteus engines. In March 1956, a Britannia 102 had flameouts in all four engines while cruising over Africa; the aircrew managed to get relights and no harm was done, but the incident unsurprisingly spooked BOAC. The problem, it turned out, was that the Proteus was a "reverse-flow" engine; it had the air intakes at the rear, with the air ducted forward through U-turns into the combustion chambers. That was apparently done to reduce length to permit fit into the Brabazon. Slush and ice would build up in the U-turns and then come loose, flaming out the combustion chambers.

As a quick fix, Bristol installed "glow plugs" in the Proteus to permit a quick and certain relight, with pilots also acquiring procedures to prevent the problem in the first place. BOAC officials, however, were slow to be reassured, and did not become so until the introduction of the Proteus 765 engine variant, which used compressor bleed air to prevent ice buildup in the ducting. It appears the glow plugs were retained.

By the time everything was resolved, international interest in the Britannia had evaporated, airliners being more interested in the Boeing 707 and other new jetliners coming into service. Britannia advocates cursed BOAC, claiming the Britannia would have been much more successful had it not for all the delays. Certainly, it would have been more so, but defenders of BOAC point out that the interim glow plug solution left something to be desired, relights occurring with a loud BANG that would have been most unsettling to passengers. It is hard to think that would acceptable in any modern turboprop airliner.

* In any case, the stretched Britannia entered production, some built at Filton, some built at a second production line in Belfast. The "Series 250" was a combination cargo / passenger aircraft; the only buyer was the British Royal Air Force (RAF), which obtained three "Britannia 252" machines -- designated "Britannia C Mark 2" in RAF service, all these machines being manufactured in Belfast -- and 22 "Britannia 253" machines -- designated "Britannia C.1" in RAF service, five of them made in Belfast, 17 at Filton. Both variants had a forward cargo door, a reinforced floor, and cargo handling gear, while the C.1 could be fitted with 115 rearward-facing seats.

Britannias in RAF service were given the names of stars, such as "Arcturus", "Sirius", "Spica", "Vega", and so on. Incidentally, at least some photos of the RAF Britannias show them to have props with rounded tips; exactly which later production machines retained the square-tipped props is unclear. There was also BOAC interest in a pure cargo machine, the "Britannia 200", but BOAC decided not to buy, and it didn't happen.

The first of the stretched Britannias to actually fly was the "Series 300", which was a passenger liner with up to 139 seats in a high-density configuration. An initial "Britannia 301" prototype was built at Filton, to be lost in a fatal crash in 1957, it is suspected due to an autopilot failure. Two "Britannia 302" machines were built for BOAC, being made at Belfast -- but BOAC then decided the baseline Series 300 wasn't quite what was wanted, and so the two were sold to AeroMexico.

BOAC interest had moved on to the "Series 305", with more fuel capacity, providing a range of 4,268 miles. However, BOAC lost interest in that as well, with all Series 305 production being for other airlines:

Although it appears early Series 300 production still used the Proteus 705 engine, later production used the Proteus 755, with 3,070 kW (4,120 HP), and the RAF Series 250 machines used the Proteus 765, with 3,315 kW (4,445 HP). The exact pattern of engine use is very difficult to determine, and it seems plausible there were engine upgrades in service, making the pattern even more confusing.

After extended indecision that appears to have driven Bristol officials to distraction, BOAC did finally settle on the "Series 310", originally "Series 300LR", with further increased fuel capacity, along with appropriately reinforced airframe and landing gear.

___________________________________________________________________

BRISTOL BRITANNIA SERIES 310:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

43.37 meters (142 feet 4 inches)

wing area:

192.9 sq_meters (2,075 sq_feet)

length:

37 meters (124 feet 3 inches)

height:

11.43 meters (37 feet 6 inches)

empty weight:

37,440 kilograms (82,535 pounds)

MTO weight:

83,915 kilograms (185,000 pounds)

max speed:

640 KPH (395 MPH / 345 KT)

cruise speed:

575 KPH (355 MPH / 310 KT)

cruise altitude:

7,320 meters (24,000 feet)

range, max payload:

2,650 kilometers (4,270 MI / 3,710 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

Following a "Britannia 311" prototype, built at Filton, Series 310 production included:

The last of 82 Bristol-made Britannias were two "Series 320" machines, amounting to an improved Series 310 with the Proteus 765, this pair of aircraft being sold to Canadian Pacific airlines.

After their lives with their initial buyers, Britannias -- including the RAF machines, which were generally retired in 1975 -- had active careers with other commercial airlines, with an emphasis on cargo haulage. The RAF machines were the only Britannias formally in military service, but the Cuban Britannias were used to ferry Cuban troops to Angola in the 1970s. The Britannia lingered in service into the 1990s.

It appears crews had mixed feelings about the "Whispering Giant", as the Britannia was nicknamed. It took a long time for Bristol to get the Proteus engine right; it seems they did after a while, but it's telling that no other production aircraft used the Proteus. The cockpit was also an icebox, Bristol apparently not getting the cockpit heating right either. However, nobody ever faulted the Proteus for a lack of power, aircrews saying the Britannia had no problems with "hot and high" conditions even with a full load; aircrews similarly praised the Britannia's handling. Certainly, few ever faulted it for looks.

BACK_TO_TOP* In 1949, Canadair of Canada began to consider a replacement for the Avro Lancaster maritime patrol aircraft operated by the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) -- with the initial focus of the investigation being a derivative of the Canadair North Star, which was a Douglas C-54 / DC-4 built under license. The RCAF came up with a formal requirement in 1952; after consideration of alternatives, the decision was made to focus on a maritime patrol derivative of the Britannia, which was only then getting into the air. In the meantime, the RCAF obtained 25 Lockheed P2V-7 maritime patrol aircraft as an interim solution.

In 1954, Canadair obtained a license from Bristol to produce the Britannia. The company gave the maritime patrol derivative the internal designation of "CL-28". Initial flight of the first CL-28 -- officially a preproduction machine, there being no need seen to build a prototype of a derivative of an existing aircraft -- was on 28 March 1957. The CL-28 was designated by the RCAF as the "CP-107 Argus", after the hundred-eyed monster of Greek mythology.

The Argus entered RCAF service in the summer of 1958, with a total of 33 delivered to end of production in 1960. Two variants were built:

The Argus only used the flight surfaces of the Britannia, fitting them to a new fuselage, and also replacing the Proteus turboprops with Wright R-3350-32W Turbo-Compound engines driving three-bladed variable-pitch propellers. The radials were noisy, but they had much better fuel economy than the turboprops, permitting long patrol endurance at low level. An Argus with a warload could cruise for over 24 hours, one doing so for 31 hours.

The unpressurized fuselage featured a glass nose for an observer / bombardier, with the cockpit featured pilot, copilot, and flight engineer -- the flight engineer had a good portion of the flight instruments and even throttles, helping to offload the pilot and copilot; apparently they would simply call back to the engineer to change throttle settings. Behind the cockpit were spaces for radio operator and navigator; galley, dining area, and four bunks; a compartment behind the wings for the systems operators; and a tail compartment, with racks of sonobuoys, flares, smoke markers, and so on, dispensed from two chutes in the floor, and two rectangular bulged windows with chairs for visual observers. The crew door, which was hinged at the top, was on the left rear fuselage; it is unclear if there were other doors elsewhere. Crew was up to 15, including relief personnel to spell other crew.

Along with the search radar, mission avionics included a magnetic anomaly detector (MAD) boom on the tail; antenna domes behind the cockpit and under the rear fuselage for electronic location gear; and a searchlight on the leading edge of the right wing. The sonar support gear included a "Julie-Jezebel" system, which used sonobuoys in conjunction with explosive charges to pinpoint submarines. The rear of the antenna dome behind the cockpit was glazed for use by the navigator for astrogation; there was a hatch to the left of this dome for escape, also being used by an aircrewman to provide guidance to the cockpit crew while taxiing.

There were dual weapons bays to carry up to 3,630 kilograms (8,000 pounds) of bombs, mines, depth charges, and homing torpedoes. Pylons could be fitted for underwing stores, but it seems that was never done operationally.

___________________________________________________________________

CANADAIR CP-107 (CL-28) ARGUS:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

43.37 meters (142 feet 4 inches)

wing area:

192.9 sq_meters (2,075 sq_feet)

length:

39.26 meters (128 feet 10 inches)

height:

11.79 meters (38 feet 8 inches)

empty weight:

36,740 kilograms (81,000 pounds)

MTO weight:

71,215 kilograms (157,000 pounds)

max speed:

505 KPH (315 MPH / 275 KT)

cruise speed:

330 KPH (205 MPH / 180 KT)

ceiling:

7,620 meters (25,000 feet)

range:

9,495 kilometers (5,900 MI / 5,130 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

At its introduction to service, the CP-107 was as sophisticated a maritime patrol aircraft as available anywhere in the world. From 1964, the Argus fleet was equipped with parachutable sea rescue kits to support its secondary search and rescue role. One CP-107 was used during the 1970s for trials of the AN/APS-94D side-looking airborne radar (SLAR) -- the boxy SLAR antenna being slung under the rear bomb bay; another was used for trials of an infrared linescanner system.

The Argus was generally liked by crews, being reliable and effective, though the engines were noisy and the vibration levels high. The CP-107 was finally phased out in 1982, being replaced by the Lockheed CP-140 maritime patrol aircraft -- another hybrid, with the airframe of the Lockheed P-3 Orion, but the operational avionics of the Lockheed S-3 Viking. Most of the CP-107s were scrapped, but a handful still survive on static display.

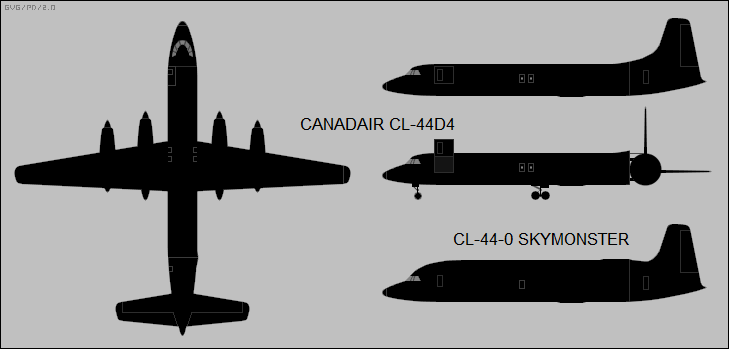

BACK_TO_TOP* One of the reasons the Britannia had been selected as the RCAF's maritime patrol aircraft to begin with was because the RCAF also had a requirement for a transport aircraft, and the Britannia was seen as the basis for both requirements. Canadair accordingly built the "CL-44" AKA "Forty-Four" airliner -- essentially a stretched Britannia 300 Series machine, powered by Rolls-Royce Tyne 11 turboprops, providing 4,100 kW (5,000 SHP) each, instead of the Proteus.

The fuselage was extended by 3.75 meters (12 feet 4 inches) relative to the Britannia Series 300, to a length of 41.63 meters (136 feet 7 inches), with large cargo doors -- featuring inset passenger doors -- fitted fore and aft of the wing on the left side of the fuselage. Maximum cargo load was 27,525 kilograms (60,680 pounds). The airframe and landing gear were reinforced to handle higher weights.

The primary rationale for the CL-44 was as a long-range personnel and cargo transport to support Canadian forces in Europe, with a contract awarded in early 1957 for what would end up being a dozen "CL-44-6" machines, which were given the service designation of "CC-106 Yukon". Nine were fitted as straight cargo haulers, while three were fitted as personnel-VIP transports. The Yukon could haul up to 134 passengers, along with a crew of nine. In the medical evacuation role, it could handle 80 patients, along with a crew of 11.

It would be nice to say that Canadair managed to dodge all the problems inflicted on the Britannia by the Proteus, but as it happened the Tyne had its problems as well, and Rolls-Royce wasn't able to fix them all right away. However, the RCAF found its Yukons very satisfactory; when they were finally phased out of Canadian service in 1973, they found good homes with civilian air hauler outfits.

Even as the Yukon was going into production, Canadair engineers were rethinking the design, coming up with the "CL-44D4" -- which was effectively a Yukon with the rear cargo door deleted, and the entire tail hinged to swing open under hydraulic power to the right, allowing straight-in cargo loading. Cabin pressure was maintained by an inflatable seal. It was one of the first "swing-tail" cargo haulers. It was powered by Tyne 12 engines, providing 4,275 kW (5,370 SHP) each -- and also featured revised cockpit glazing, with fewer panes but more total area. 23 CL-44D4 machines were built in all, the most prominent user being Flying Tiger Lines. Canadair offered a swing-tail "CL-44G" to the RCAF, but it didn't happen.

___________________________________________________________________

CANADAIR CL-44D4:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

43.37 meters (142 feet 4 inches)

wing area:

192.9 sq_meters (2,075 sq_feet)

length:

41.73 meters (136 feet 11 inches)

height:

11.43 meters (37 feet 6 inches)

empty weight:

37,440 kilograms (82,535 pounds)

MTO weight:

83,915 kilograms (185,000 pounds)

max speed:

640 KPH (395 MPH / 345 KT)

cruise speed:

575 KPH (355 MPH / 310 KT)

cruise altitude:

7,320 meters (24,000 feet)

range, max payload:

2,650 kilometers (4,270 MI / 3,710 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

Four "CL-44D4-8" airliners were sold to the Icelandic airline Lofteleior, these machines being CL-44D4 freighters kitted up as airliners, passenger capacity being 160 to 178 passengers, with the swing-tail retained but nonfunctional. The last was actually delivered as the "CL-44J", with a 4.6 meter (15 feet 2 inch) fuselage stretch to 46.34 meters (152 feet), providing up to 214 seats; the three CL-44D4-8 airliners were then updated to CL-44J spec. The stretched CL-44s were arguably the most elegant of the Britannia line.

A total of 12 + 23 + 4 == 39 CL-44 aircraft was built in all. One of the CL-44D4 machines was converted into a bulk-cargo carrier, with an oversized fuselage and retaining the swing-tail, by Jack Conroy, the mastermind behind the "Guppy" bulk-cargo modifications of the Boeing Stratocruiser. This aircraft was designated the "CL-44-0" and named the "Skymonster". The CL-44 lingered in service to the end of the century; some survive on static display.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Brabazon Type II originally defined what would now be called a small commuter airliner, but in time that specification evolved -- resulting in two sub-specifications, neither of which were a close match to the original Type II specification, with the original specification becoming the "Type V", with two sub-specifications as well. Enough to say that the Type IIB specification became the Vickers "Viscount" -- pronounced "VAI-count", by the way -- while the Type VB specification became the de Havilland "Dove" -- which is to be discussed elsewhere.

From the outset, the Type IIB was to have four turboprop engines. As originally defined, it was to have 24 seats, but then BEA came back and asked for 32. A formal contract, to Air Ministry Specification C.16/46, was issued in March 1946, with two "Type 609" ordered. The Type 609s were to be powered by the Armstrong Siddely Mamba turboprop -- but Vickers engineers saw the Mamba, based on newfangled "axial-flow" turbine technology, as much riskier than the competing Rolls-Royce Dart turboprop, based on well-established "centrifugal-flow" turbine technology. Vickers consequently designed the engine nacelles to accommodate either the Mamba or the Dart.

The development of the Dart proceeded more smoothly than that of the Mamba, so in 1947 the government specified the Dart instead of the Mamba, the prototypes receiving the new designation of "Type 630 Viscount" -- Britain having granted independence to India, the name "Viceroy" had become antiquated. The Dart would prove one of the most popular and successful first-generation turboprops, vindicating the judgement of Vickers engineers. It was powerful, reliable, and rugged, one Rolls-Royce official describing it as "agricultural machinery".

Development went smoothly under the competent leadership of Vickers chief engineer George (later Sir George) R. Edwards. The first Type 630 prototype performed its initial flight on 16 July 1948, with Joseph "Mutt" Summers and G.R. "Jock" Bryce in the cockpit. It was powered by Dart RDa.1 Mark 502 engines with 740 kW (990 EHP) each. Trials went generally well from the outset.

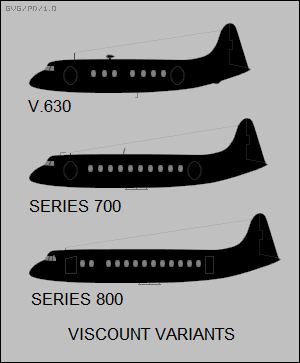

The Type 630, as it emerged, had 32 seats -- which BEA judged as too small, meaning it was nonstarter as it was. The focus then went on to a stretched version with more powerful Dart engines, not just to handle higher weights but to improve performance, this variant being the "Type 700"; wingspan was also extended, mostly to increase lift but also to reduce cabin noise by placing the engines farther away from the fuselage. However, the first Type 630 prototype was seen as interesting enough by BEA to put it into commercial service as an evaluation exercise, carrying passengers between London and Paris, as well as London and Edinburgh, for a month. Its initial commercial flight, on 29 July 1950, took 14 passengers from London to Paris, this said to be the very first commercial flight of a turboprop airliner.

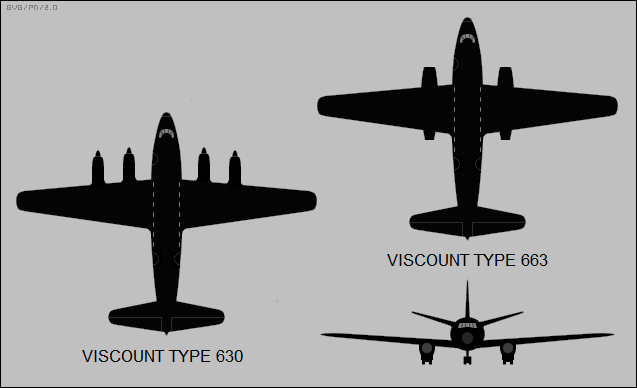

The second Type 630 prototype was actually completed with twin Rolls-Royce Tay turbojet engines as the "Type 663", with initial flight on 15 March 1950. Some sources claim the British missed a bet by not pursuing the Type 630 further, but it was built strictly as an engine testbed for the RAF, with no real thought, much less a requirement, for a small turbojet airliner. The Type 663 would be used later in other trials.

A third "Type 640" prototype had been planned, to be powered by Napier Naiad turboprops, but it was completed as the Type 700 Viscount prototype. The prototype performed its initial flight on 28 August 1950, this machine having a passenger capacity of 48 seats -- or as it would turn out, 53 seats in a higher-density configuration. It was powered by Dart RDa.3 Mark 506 engines, providing 1,045 kW (1,400 SHP) each, to handle the higher airframe weight. It was all that was hoped for, and BEA placed an order for 20 production "Viscount 701" machines, with orders for more coming in from other airlines, including Air France and Aer Lingus, during the course of 1951.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Viscount 701, as it emerged, was a homelier design than the elegant Britannia, but had a certain admirable utilitarianism to it. It was of all-metal construction, with a low wing and tricycle landing gear. It had large oval windows -- 48x66 centimeters (19x26 inches) -- giving a view greatly enjoyed by passengers, as well as large oval doors, on the left side of the fuselage fore and aft of the wing, hinged forward. The oval configuration was to deal with cabin pressurization, stress from pressurization tending to be focused at the corner of rectangular doors and windows; it was precisely this issue that led to fatal losses of the DH Comet, and derailed the program.

___________________________________________________________________

VICKERS VISCOUNT 700:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

28.56 meters (93 feet 8 inches)

wing area:

89.5 sq_meters (963 sq_feet)

length:

24.74 meters (81 feet 2 inches)

height:

8.15 meters (26 feet 9 inches)

empty weight:

15,580 kilograms (34,360 pounds)

MTO weight:

26,530 kilograms (58,500 pounds)

cruise speed:

370 KPH (320 MPH / 280 KT)

cruise altitude:

7,620 meters (25,000 feet)

range (full load):

2,255 kilometers (1,400 MI / 1,217 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

The wings had a slight dihedral, the tailplane a stronger dihedral; the tailfin had a forward fin fillet. Flight control surface arrangement was conventional: double slotted flaps, ailerons, rudder, elevators. The Dart engines drove four-bladed props. All landing gear assemblies had twin wheels and all retracted forward; the nose gear was steerable, the main gear retracted into the inboard engine nacelles. The four Darts tended to shriek on startup, but once on cruise the Viscount was a pleasant ride, one early report commenting:

BEGIN QUOTE:

Noise level was less than that of piston engines. It was a definite relief to be rid of the rough vibrations ... The turboprop is an excellent shorthaul airplane and a definite crowd pleaser. The substitution of a lower constant pitch noise and smoothness for the vibration, grunts, and groans of the piston engine gives the hesitant passenger a feeling of confidence.

END QUOTE

There was a long list of Viscount Series 700 subvariants, effectively one for each customer, with some variants kitted up for the North American market -- featuring more electrical power, rearranged interior, provisions for cold weather operation, and so on.

The Series 700 gave way to the "Series 700D", which was powered by uprated to the Dart RdA.6 Mark 510 engine in later production, with each providing 1,195 kW (1,600 SHP). It appears that Viscount 700D machines could be fitted with a "slipper" fuel tank on each outer wing with a capacity of (145 Imperial gallons) each, though it is hard to find any photos of Viscounts with the tanks.

Success of the Series 700 Viscount led to the further stretched "Series 800" Viscount, which had a capacity of 65 to 71 seats; it had airframe reinforcement to deal with further increased weight, and replaced the oval doors with more conventional rectilinear ones. It originally was powered by the Dart RdA.6 Mark 510. Again, there was a large number of subvariants as per customers, with some later production featuring Dart RdA.7 Mark 520 engines providing 1,265 kW (1,700 SHP), permitting higher MTO.

The "Series 810" was the definitive Viscount, powered by Dart RDa.7/1 Mark 525 engines, with 1,240 kW (1,800 SHP), substantially reinforced airframe, higher MTO, and faster cruise speed. A "Series 840" was considered, with further uprated Dart RDa.8 engines, but not built.

A total of 445 Viscounts was built in all, up to end of production in 1964. Some were kitted up as VIP transports, or used for radar and other avionics trials. While never able to challenge American dominance of the airliner market in the postwar period, it was still a clear success story for Britain's aircraft industry. Viscounts lingered in service into the next century.

BACK_TO_TOP* The success of the Viscount led to consideration of a follow-on, with a nominal passenger capacity of 100 seats, but mostly redesigned. The result was the Vickers "Type 950 Vanguard", which performed its initial flight on 20 January 1959, with Jock Bryce at the controls. It entered service the next year, 1960.

Anyone first seeing a Vanguard after being used to the Viscount would recognize the Vanguard as a descendant, since it had such a similar configuration -- same general flight surface arrangement, same landing gear arrangement, similar door arrangement. The most significant difference between the Vanguard and Viscount was that the Vanguard featured a "double-bubble" fuselage, providing more passenger space and, below deck, more cargo space, making the Vanguard something of a "combi" aircraft. The cockpit was also redesigned, featuring a rakish snub nose.

The Vanguard was powered by four turboprops -- Rolls-Royce Tyne R.Ty1 Mark 506 engines, with 3,714 kW (4,985 SHP) each, driving four-bladed variable-pitch props, well more powerful than the Viscount's Darts. Performance was excellent for an aircraft of its class, indeed some judged the Vanguard as overpowered. Initial seating was 18 first-class, four seats across, at the rear; and 108 economy, six seats across -- but that was changed to 139 economy seats.

___________________________________________________________________

VICKERS VANGUARD:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

36.14 meters (118 feet 7 inches)

wing area:

142 sq_meters (1,527 sq_feet)

length:

37.45 meters (122 feet 10 inches)

height:

10.64 meters (34 feet 11 inches)

empty weight:

37,420 kilograms (82,500 pounds)

MTO weight:

63,975 kilograms (141,000 pounds)

max cruise speed:

685 KPH (425 MPH / 370 KT)

service ceiling:

9,145 meters (30,000 feet)

range, max payload:

2,945 kilometers (4,100 MI / 1,591 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

The Vanguard did not prove very successful; it was not able to compete with jet airliners then being introduced in its category. Including the prototype, only 44 Vanguards were built, being ordered by BEA and Trans-Canada Air Lines (TCA), the last delivered in 1962. Three production variants were made:

After a decade of service, TCA converted one of theirs to a freighter configuration, naming it the "Cargoliner", capable of hauling 19,050 kilograms (42,000 pounds) of cargo -- some sources hint at other TCA conversions, but give no specifics. The last TCA flight of a Vanguard, a Cargomaster, was in 1974. BEA performed nine similar conversions, naming them the "Type 953C Merchantman". The Merchantmen lingered in service into the 1990s.

BACK_TO_TOP* I recall the Viscount because our family took a vacation to Hawaii in 1965, and we took a Viscount on a jaunt from Oahu to Hawaii, the "Big Island". I remember it because the oval windows seemed so big compared to other airliners I had flown on -- of course, I was much smaller at the time. I did not realize, however, that I was mispronouncing the name as "VIS-count", not the correct "VAI-count", until I wrote this document. That seems to have been a common error.

* Sources include:

There was also considerable reference to the online Wikipedia.

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 oct 14 v1.0.1 / 01 sep 16 / Review & polish. v1.0.2 / 01 aug 18 / Review & polish. v1.0.3 / 01 jun 20 / Review & polish. v1.0.5 / 01 may 23 / Review & polish. v1.0.6 / 01 may 25 / Review & polish.BACK_TO_TOP