* Canada and the US collaborated closely on the defense of North America during the Cold War. While the US was clearly the bigger partner in the defense relationship, the Canadians carried their weight, and provided their own distinctive contributions to the partnership. One of the more memorable was the "Avro CF-100 Canuck" interceptor. This straightforward and effective machine served as one of the mainstays of North American air defense through the 1950s.

Avro Canada wanted to follow the Canuck with a truly advanced aircraft, the Avro "CF-105 Arrow". The Arrow was a huge, twin-engined delta-winged interceptor that in completion would have been able to attain Mach 2.5, but costs and changing mission requirements kept it from ever leaving the prototype stage. This impressive machine represented the highest ambition of Canadian aircraft design and remains a romantic ideal for Canadian aviation enthusiasts. This document provides a history and description of the CF-100 Canuck and the CF-105 Arrow. A list of illustration credits is included at the end.

* The CF-100 grew out of a January 1945 Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) requirement for a twin-jet, radar-equipped all-weather interceptor. Avro Canada, which had been established by the British Hawker Siddeley group in July 1945 through purchase of the Victory Aircraft plant, got the formal contract to develop the new aircraft under AIR Spec 7-1 in October 1946. The contract specified construction of two flight prototypes and a static test airframe, all with the designation of "XC-100". Development was performed by a team led by the company's chief engineer, John Frost.

The two prototypes were to be powered by twin British Rolls-Royce Avon axial-flow turbojets, but that was strictly an interim engine fit. The Gas Turbine Engine branch of Avro Canada had developed their own axial-flow engine, the "TR4 Chinook", which they then scaled up to the excellent "TR5 Orenda" for the CF-100. Initial test runs of the Orenda were performed in 1949, with results meeting or exceeding expectations.

* The initial "CF-100 Mark 1" prototype, as the XC-100 had been redesignated, performed its initial flight on 19 January 1950, with the aircraft given a snappy overall black color scheme detailed with white lighting bolts running down the sides. Since Avro Canada's test pilots didn't have fast jet experience at the time, first flight honors were performed by Bill Waterton, a Canadian who was the chief test pilot of the British Gloster firm, part of the Hawker Siddeley group. The Mark 1 was powered by two Avon RA.3 turbojets with 28.9 kN (2,950 kgp / 6,500 lbf) thrust each. Performance and handling were up to spec, but the wings flexed too much. That would be a serious issue in early development, aircraft having a nasty tendency to land with cracked wing spars. The problem was a major threat to the program and wouldn't be finally resolved until 1952.

The second prototype performed its first flight in July 1950; it was effectively identical to the first prototype. Its trials included a session at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, where US Air Force pilots got a chance to fly the machine, and were impressed by it. One of the main roles of the second prototype was evaluation of wingtip fuel tanks, which imposed unacceptable stresses on the wings until a fin was attached on the outboard side of each tank. The fins improved overall flight stability as well.

* The CF-100 prototypes set the basic design for the series. The machine was of simple and clean configuration, with a low mounted straight wing and twin jet engines, each mounted in a nacelle next to the fuselage. The fuselage was loaded with fuel tanks and had tandem seating, with the pilot in front and a radar operator in back. Both sat on Martin-Baker ejection seats in a pressurized cockpit, under a canopy that slid back on rails to open.

The wing featured double slotted flaps, airbrakes on both top and bottom, and leading-edge pneumatic de-icing boots. All flight controls were hydraulically actuated. The CF-100 had tricycle landing gear, with the nose gear retracting backward and the main gear hinged in the wings to retract inward to the fuselage. All the gear assemblies had twin wheels to handle the machine's relatively heavy take-off weight.

The second prototype crashed near London, Ontario, on 5 April 1951, with both crew killed; the cause was believed to be a failure of the crew oxygen system that knocked out the pilot. The first prototype remained in trials service through the 1950s, to be finally scrapped in 1965.

BACK_TO_TOP* In July 1949, even before the first flight of the Mark 1, ten unarmed "CF-100 Mark 2" development machines had been ordered. The first, with twin Orenda 2 engines providing 26.7 kN (2,720 kgp / 6,000 lbf) thrust each, performed its initial flight on 20 June 1950. As it turned out, this machine would be the only real Mark 2 as such. The next four in the batch were built as trainers with dual controls and designated "Mark 2T". These five machines were used both for initial RCAF familiarization training and for trials. There was a scheme to build a photo-reconnaissance variant of the Mark 2, designated the "Mark 2P", using one of the Mark 2 evaluation airframes, but this program was canceled.

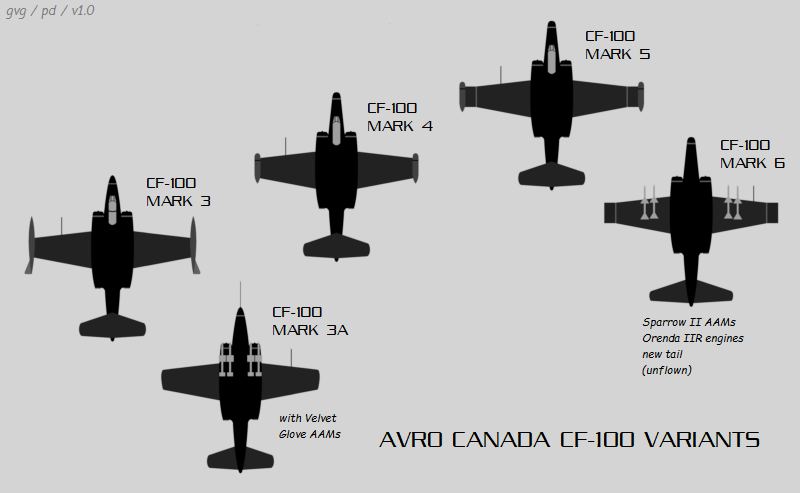

The success of the flight-test program led to an initial production order in September 1950 for 124 "CF-100 Mark 3s". The initial Mark 3 performed its first flight in September 1952 and entered squadron service with the RCAF in April 1953, to be given the name "Canuck". The RCAF never actually liked the name much in practice, and pilots and crews would generally call it the "Clunk".

The Mark 3 was fitted with a US-built Hughes E-1 fire control system, organized around an AN/APG-33 radar mounted in the nose, the same radar as fitted to the CF-100's American counterpart, the Northrop F-89A Scorpion. Armament consisted of eight 12.7-millimeter (0.50-caliber) Browning machine guns in a belly tray that could be dropped out for fast servicing. Trials were conducted with a tray containing four 20-millimeter cannon, but technical problems led to the abandonment of this weapons fit. The Mark 3 featured a pitot tube on the left wing; earlier aircraft had been occasionally fitted with a nose pitot tube during trials. The Mark 3s generally flew in natural metal finish.

Two stores pylons could be fitted under each wing, for a total of four, for carriage of munitions, such as four 450-kilogram (1,000-pound) bombs. However, though the test program had included bombing trials, the CF-100 would never be assigned to the attack role operationally. Trials also included tests of "rocket assisted take-off gear (RATOG)", but though the scheme worked well, it was also not used operationally.

Another test fit evaluated by the Mark 3 was the "Velvet Glove" radar-guided air-to-air missile (AAM), with four missiles carried on the underwing pylons, or in some trials on pylons under the fuselage and engine intakes. Velvet Glove was a collaborative effort conducted by Canada, the US, and the UK; most of the missile was designed in Canada, with a solid-rocket motor provided by the US. The program was canceled in 1956 and Velvet Glove never entered service.

Only 70 Mark 3s were actually built, not counting four pre-production machines that had actually started life as part of the batch of ten Mark 2 pre-production aircraft; these four aircraft were built as "Mark 3T" dual-control trainers. Of the 70 production Mark 3s:

In service, the Mark 3 was promising, but it suffered from a number of teething problems; the Mark 3s amounted in effect to training and evaluation machines. One problem was that the control stick obscured the compass, a problem that was fixed in the field by modifying the stick. A second problem was a manual fuel control system that was too workload-intensive; the fuel system was also overly complicated and unreliable. Other annoyances were lack of nosewheel steering and unreliable landing gear.

When the Mark 3 was supplanted by improved versions of the Canuck, 4 Mark 3A and 43 Mark 3B machines were converted by Bristol Canada to "Mark 3D" dual control trainers, with the Mark 3As upgraded to Orenda 8 engines in the process. This exercise was followed by conversion of 9 Mark 3CTs to the Mark 3D standard, with these aircraft retaining Orenda 2 engines.

* In the meantime, the RCAF decided to adopt the American practice of using clusters of unguided 70-millimeter (2.75-inch) "Mighty Mouse" folding fin rockets as an air-to-air weapon, instead of guns. One of the Mark 2Ts was used for initial trials of wingtip-mounted rocket pods.

The first operational variant to carry the rockets was the "CF-100 Mark 4", with the initial prototype, which had started life as the last of the ten pre-production Mark 2s, performing its first flight on 11 October 1952. It could outrun its Sabre chase plane, though it was nowhere near as agile as the Sabre. The prototype even broke Mach 1 in a dive on 4 December of that year. It was used for evaluation of a belly rocket pack, mounted behind the gun pack, that could carry 48 FFARs. The belly pack caused severe buffeting when it was extended, and was abandoned. The Mark 4 prototype was lost during trials with this weapons fit on 23 August 1954, the pilot ejecting successfully but the back-seater being killed.

The first production Mark 4 was rolled out in September 1953. The Mark 4 featured:

Early production Mark 4s lacked an autopilot; it is unclear if they were refitted with one later. Most Mark 4 production had a tail bumper, but it was deleted from late production aircraft.

The Mark 4 was the first honestly satisfactory CF-100 variant, and so the last the Mark 3 order was cut short, ending Mark 3 production as mentioned at 70 aircraft. 137 Mark 4s were built, and then the uprated Orenda 11 engine, with 32.4 kN (3,300 kgp / 7,275 lbf) thrust, was introduced as a production change; 193 of these souped-up Mark 4s were built and designated "Mark 4B", with the 70 Orenda 9 powered machines retroactively redesignated "Mark 4A". Two of the Mark 4As were converted to Mark 4B configuration.

* The last CF-100 variant was the "Mark 5", which had a simple straight 1.06-meter (3.5-foot) extension to each wingtip and wider tailplane to increase the type's operational ceiling. The Mark 5s were powered by Orenda 11s, or Orenda 14s with similar thrust. The Mark 5s were armed solely with wingtip rocket pods, the gun pack and gunsight being deleted. Wing leading-edge de-icing boots and the unused fittings for RATOG were also deleted to reduce weight.

First flight of the Mark 5 prototype was in September 1954, with first flight of a production item on 12 October 1955.

___________________________________________________________________

AVRO CANADA CF-100 MARK 5 CANUCK:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

17.75 meters (58 feet)

wing area:

54.9 sq_meters (591 sq_feet)

length:

16.7 meters (54 feet 2 inches)

height:

4.76 meters (15 feet 6 inches)

empty weight:

10,480 kilograms (23,100 pounds)

loaded weight:

16,800 kilograms (37,000 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

1,110 KPH (690 MPH / 600 KT)

service ceiling:

16,460 meters (54,000 feet)

range:

4,000 kilometers (2,500 MI / 2,175 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

281 Mark 5s were built as new production, and 49 Mark 4Bs were upgraded to the Mark 5 standard. A total of 693 Canucks was built in all; it was the only Canadian-designed jet fighter to ever reach production.

The CF-100 served with nine RCAF squadrons at its peak, in the mid-1950s. Four of these squadrons were deployed to Europe from late 1956 into 1962 under the NIMBLE BAT ferry program, replacing squadrons equipped with Canadair Sabre day-fighters to provide all-weather defense against Soviet intruders. Canucks flying at home retained natural metal finish, but those flying overseas were given a British-style disruptive camouflage scheme -- dark sea gray and green on top, light sea gray on the bottom.

Following the end of the CF-100's first-line service, a small number of Mark 5s were refitted as electronic countermeasures aircraft. The initial conversion was the "Mark 5C", featuring active radar jammers, fitted in the gun pack bay, and chaff dispensers on underwing pylons. The wingtip extensions were removed and wingtip tanks were carried as standard. These machines were followed by "Mark 5D" conversions, which added active communications jamming gear. They stayed in service until 1981 and were the last CF-100s to fly for the RCAF. For the farewell flight, at least one was painted black with white lightning bolts up each side of the fuselage, the same paint scheme used on the initial Mark 1 prototypes.

53 Mark 5s were also provided to the Belgian Air Force, all being filtered through the RCAF and with initial deliveries in late 1957. They flew using the same disruptive camouflage scheme applied to RCAF CF-100s in Europe. The Belgian Mark 5s were retired in the early 1960s, and all were scrapped. Not one made its way to an air museum; in 1971 a Belgian air museum bought a Canadian CF-100 for the princely sum of a Canadian dollar, with the Belgians displaying it with its original RCAF markings.

* A total of 683 CF-100s was built. The following list provides a summary of CF-100 variants and production:

* There were a number of special variants and modifications of the Canuck:

There were several concepts for a "Mark 6", such as a machine with afterburning Orenda 11R ("reheat") engines and Sparrow armament. The "Mark 7" was to feature a thinner wing and Sparrow armament. The "Mark X" was a concept for a high-altitude machine that added a Bristol Orpheus turbojet to each wingtip; and the "CF-103" was a swept-wing version of the Canuck. None of these machines were built.

BACK_TO_TOP* The success of the CF-100 Canuck led Avro Canada to consider an improved replacement. Initial concepts were of modified CF-100s with swept wings, and then the designs evolved to delta-winged aircraft.

In April 1953, after a year of analysis by Avro, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) presented a requirement for a twin-engined, two-seat interceptor with a maximum speed of Mach 2+, a maximum ceiling of 18.3 kilometers (60,000 feet), and a combat radius of 370 kilometers (200 nautical miles). It would have a fast rate of climb and would be able to maneuver at two gees at high speed and altitude, an extremely difficult requirement to meet. The new aircraft would be armed only with missiles stored in an internal weapons bay, and would use a sophisticated radar fire-control system to allow collision-course intercepts, instead of tail-chase pursuit. The result was the Avro "CF-105 Arrow".

* The Arrow was conceived in response to the threat posed by fleets of Soviet nuclear-armed bombers, then believed to be under construction, cruising into North American airspace from over the poles. It seemed crucial to have a weapon that could intercept and destroy these intruders over the empty northlands before they reached Canadian and American cities farther south.

The RCAF requirements implied a big aircraft. The final design had a boxy fuselage and a slightly drooping high-set delta wing, with a sweep of 60 degrees and a "dogtooth" leading edge. Although most of the airframe was made of magnesium, key parts were made of titanium to withstand the heat of high-speed flight, and an environmental control system was provided to protect the crew against high flight temperatures, as well as the extreme cold of the Canadian north.

The high wing led to long landing gear, with main gear legs some 3.65 meters (12 feet) in length. The nose gear retracted forward, while the main gear hinged in the wings to retract towards the fuselage. The nose gear had twin side-by-side wheels, while each of the main gear had two wheels, arranged in a tandem configuration to allow storage in the wing. Delta winged aircraft tend to land "hot", and so a drag chute was fitted in the tail cone.

The RCAF had originally requested two hand-built engineering prototypes, but decided that the project was too urgent, and that flight tests would be done on a handful of preproduction prototypes. Since that meant expensive production tooling would have to be in place before the Arrow ever flew, this requirement stepped up the pressure on the design team, who were forced to implement extensive preflight testing to ensure that the preproduction prototypes operated as intended.

Wind tunnel tests were used to refine the aircraft's aerodynamics, which were tuned by the application of the "area rule" contour. This scheme was devised by an American, Richard T. Whitcomb, then at the US National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA, one of the precursors of NASA) Langley Research Center in Virginia. The principle behind area ruling was to minimize abrupt changes in aircraft cross-section to improve transonic handling. In practice, it dictated a fuselage with "Coke bottle" streamlining.

Eleven free-flight models of the Arrow were launched on Nike boosters from the end of 1954 to the beginning of 1957 to validate the aircraft's design. For whatever reason, the Nike boosters were fitted with a large tailfin and a wide-span tailplane. Two of these flights were conducted at the NACA facility at Langley Field, Virginia, in order to use NACA's sophisticated tracking and telemetry equipment. The others were conducted in Canada over Lake Ontario; in recent years, Arrow enthusiasts have been searching the waters of the lake to find some of the flying Arrow models that were lost there.

After much consideration of alternatives, the Orenda PS-13 Iroquois engine was chosen as the powerplant. Since this engine would not be ready in time for initial flight tests, an alternate engine was needed for early flight testing. The Avro team originally selected the new Rolls-Royce RB.106, but development of that engine was delayed in turn, and the Pratt & Whitney J75, used on the Republic F-105 Thunderchief and Convair F-106 Delta Dart, was chosen to power the preproduction prototypes, which were designated "Mark 1". Prototype development would in principle then evolve to the Iroquois-powered "Mark 2", resulting in an aircraft that would be capable of Mach 2.5. The production model would be designated "Mark 3".

___________________________________________________________________

AVRO CANADA CF-105 ARROW MARK 2 (ESTIMATES):

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

15.24 meters (50 feet)

wing area:

113.80 sq_meters (1,225 sq_feet)

length:

25.3 meters (83 feet)

height:

6.25 meters (20 feet 6 inches)

empty weight:

22,250 kilograms (49,000 pounds)

max loaded weight:

31,100 kilograms (68,600 pounds)

maximum speed:

3,200 KPH (2,000 MPH / 1,740 KT)

service ceiling:

18,300 meters (60,000 feet)

operational radius:

660 kilometers (410 MI / 355 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

The J75 had a dry thrust of 76.5 kN (7,800 kgp / 17,200 lbf) and an afterburning thrust of 109 kN (11,110 kgp / 24,500 lbf). The Iroquois was the most powerful engine in North America, with a dry thrust of 82.4 kN (8,400 kgp / 18,500 lbf) and an afterburning thrust of 115.8 kN (11,800 kgp / 26,000 lbf). It had an unprecedented 5:1 thrust-to-weight ratio, achieved partly by extensive use of titanium.

The Iroquois was ground-tested in 1955. In 1957, the US Air Force loaned a B-47E Stratojet bomber to the Canadians for a flight-test platform. The engine was bolted to the side of the aircraft, near the tail; the lopsided bomber was apparently something of a handful to fly. Some snags were encountered in testing, but in general the engine development effort went well. The Iroquois was removed from the B-47E after the completion of trials, and the bomber was returned to the United States. However, apparently its airframe had been warped by the asymmetric thrust of the Iroquois, and the aircraft was scrapped. Interestingly, this particular B-47E was the only American strategic jet bomber that was ever operated by a foreign country.

The Arrow's two crewmen sat under clamshell-type canopies. Visibility was not the best, particularly for the back-seat radar operator, who only had small window panels on either side, but the cockpit layout was superb. Martin-Baker ejection seats were provided. An automatic flight control system (AFCS) was developed that could operate in several modes, and in principle could even land the Arrow automatically or compensate for severe damage to the aircraft. Control surfaces were hydraulically operated and electronically controlled; the Arrow was one of the first "fly-by-wire" aircraft ever built.

The armament system was devised as a replaceable pack that could be plugged into the aircraft's big weapons bay, which was 5.5 meters (18 feet) long. This allowed different weapons systems or fuel tanks to be fitted as required, with all armament carried internally.

The armament system would prove to be the biggest weakness of the Arrow project. At the beginning of the project, the CF-105 was specified to use the American Hughes MX-1179 fire control system, directing eight AIM-4 Falcon AAMs carried in a huge internal weapons bay. The MX-1179 was in development; it would emerge later, after some difficulties, as the MA-1 fire control system for the F-106. The Falcons were available and were in principle proven technology, though experience in the 1960s with AAMs would show the confidence of 1950s designers in their guided weapons to be somewhat misplaced.

In 1955, the RCAF changed their minds and decided that they wanted new technology, in the form of the RCA Victor Astra radar and fire control system, and an advanced version of the Raytheon Sparrow, the Sparrow II. The Arrow would carry four Sparrow IIs as well as the eight Falcons. While the RCAF had been dithering about the weapons fit to the point where Avro engineers had simply designed the fire-control system as a modular pack that could be upgraded, the engineers still protested at such a drastic change in plans while their program was well under way, as well as at the adoption of completely unproven technology. Their fears were justified. The Astra fire control system was complicated, and its development was to be full of problems.

Sparrow II was also problematic. The existing Sparrow I was a "semi-active" missile, with a guidance seeker that only included a receiver system that tracked emissions from the launch aircraft's radar. That meant that the launch aircraft had to keep the target "illuminated" all the way to missile impact. Sparrow II was to have a complete, compact radar system with both transmitter and receiver; it would be, in modern terms, a "fire and forget" missile. The program did not go smoothly, and the US Navy canceled Sparrow II in 1956. The RCAF decided to revive the project, Canadair working with Douglas, the original contractor on the program.

BACK_TO_TOP* While the Arrow's development seemed to be going well, perceptive observers could see the program was running out of steam. Missiles seemed to be the way of the future for both defense and offense. Improved anti-aircraft missiles seemed able to deal with Soviet bombers, which American intelligence, through the use of the new U-2 spy plane, had discovered were by no means as numerous as had been thought. In any case, the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) made visions of squadrons of such bombers streaking in over the Arctic obsolete, since ICBMs could not be effectively intercepted by any technology available at the time.

In 1957, the new Conservative Canadian government under Prime Minister John Diefenbaker cut the number of Arrows planned down to 100, escalating unit cost. Nonetheless the first Arrow Mark 1, Number 201, was rolled out on 4 October 1957, and flew for the first time on 15 March 1958. The day of the initial roll-out, 4 October, was by coincidence the same day that the Soviet Union launched the first artificial Earth satellite, Sputnik I, hinting that the threat that the Arrow had been designed to deal with was moving to higher ground.

Number 201 continued its test flights, demonstrating fine handling characteristics, and exceeding Mach 1.5 on its 7th flight. On its eleventh flight it suffered a landing gear failure and ended up performing a belly landing, but it was straightforward to repair the damage, and Number 201 was flying again by early October. Four more Mark 1s were delivered between August 1958, and January 1959.

Despite these milestones, the program was disintegrating. In late September, the Astra radar and associated Sparrow II AAM were canceled, to be replaced by a combination of the Falcon and a pair of nuclear-armed unguided Genie missiles. That was a hint of things to come.

In August, the Canadian government sent a mission to the US Air Force to sell them on the Arrow, but the USAF wasn't interested. The Americans countered by promoting the Boeing BOMARC-B anti-aircraft missile, with a range of over 700 kilometers (435 miles) -- which seemed perfectly able to defend against intruding bombers, though the BOMARC would prove to have problems of its own, suffering from an unreliable guidance system and other troubles. The Diefenbaker government bought on to the BOMARC, while tentatively hanging on to the Arrow program at the same time.

However, Canada was in a recession, and the Arrow had become the most expensive single defense project the country had ever taken on. The Canadian Army and Navy were reluctant to sacrifice their own programs to support the aircraft. RCAF Air Marshall Hugh Campbell understood the politics, and told the Defense Ministry that he would accept cancellation of the Arrow if he could obtain an alternative high-performance interceptor.

On 20 February 1959, Prime Minister Diefenbaker canceled the CF-105, with the order taking effect immediately. The prototype Arrows had completed 66 flights, for a total of 70 hours of flying time. The first Mark 2 prototype was almost ready for flight tests, with four more Mark 2s virtually complete. All the Arrows built or in production were scrapped, and design documentation and production tooling were generally disposed of. None of the Iroquois-powered Mark 2s ever flew.

Avro ended up laying off 14,000 workers. The layoffs were a massive shock to Canada's aircraft industry, and the day of the Arrow's cancellation has been known as "Black Friday" ever since. Air Marshall Campbell obtained 66 F-101B/F Voodoo supersonic interceptors from the United States to handle his air-defense requirements. The F-101B/F was a perfectly state-of-the art aircraft for the time, capable of Mach 1.5, having gone into USAF service that same year, 1959. The Voodoos were delivered in 1961 and 1962; they were taken from USAF stocks, but they had very low flight hours. They were updated in Canadian service to keep them current, to be generally phased out of service in the early 1980s.

* As noted, Canadian aviation enthusiasts hold the Arrow near and dear to their hearts, and in the minds of some it has become cherished as a Lost Cause. The wisdom of and motives behind its cancellation remain hotly debated, at least among the fringe. The facts in the case seem remarkably complicated, and it is unlikely there is any one person who was in a position to have a clear understanding of them at the time or later.

The Diefenbaker government is often singled out as irrationally hostile to the Arrow, insisting on its cancellation out of ignorance of the facts. The destruction of Arrow prototypes, components, tooling, and documentation is sometimes blamed on Diefenbaker himself -- but it appears that was not the case. The Arrow was highly advanced secret technology, and it was all destroyed since keeping the program materials and data under secure lock and key would have been troublesome. Nobody wanted to bother with the expense.

The high costs of the Arrow are given by some as a compelling reason for the government to cancel the aircraft, while others maintain that costs were inflated by unrealistic assumptions. The absence of any mention of a particular champion for the Arrow within the Canadian government makes the consideration even murkier. Others accuse the Americans of deliberately sabotaging the Arrow program. In fact, this assertion has evolved into a full-blown conspiracy theory, given widespread exposure north of the border by a two-part TV movie released in 1996 by the Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC) on the development of the Arrow, starring Dan Ackroyd. The movie apparently features scenes such as one where US President Eisenhower pressures Prime Minister Diefenbaker to cancel the Arrow and "buy American". The movie was labeled as a "work of fiction" and had elements that were clearly inventions of scriptwriters, but it apparently did much to convince people that the conspiracy theory is an indisputable fact.

In reality, the Arrow conspiracy theory, like all good conspiracy theories, is long on emotions, contrived arguments, and assertions, but short on honest evidence. Conspiracy theorists claim the US defense secretary told his Canadian counterpart that Canada would be better off to drop the Arrow and purchase US hardware, while one Diefenbaker cabinet member much later insisted that the US was highly supportive of the program, calling the conspiracy theory "nonsense".

The US did try to sell the Canadians on BOMARC, but at the same time the Americans were clearly involved with and supportive of the Arrow program from its early days -- with NACA providing test support, a B-47 provided to help test the Iroquois engine, and US hardware like the J75 engine fitted to the prototypes. After all this time, the conspiracy tale seems tiresome, but it seems to remain one of the major Canadian conspiracy theories. Incidentally, in 1980, the CBC did produce a documentary show on the Arrow that was much less sensationalistic than the movie.

There is little doubt that the Arrow would have been a magnificent aircraft, and it was certainly a shame the Iroquois-powered prototypes never flew, but on the same coin, it is apparent that the program was extremely ambitious and risky. The RCAF requirements were gold-plated, and the aircraft was based on almost entirely new technology, including the airframe, engine, fire control system, and missiles. The mission focus was also specialized by modern standards, with the aircraft sold entirely as an interceptor, and by the time the Arrow prototypes were flying, the Soviet bomber threat seemed less substantial since ICBMs were clearly going to be in service soon. The combination of circumstances was more than enough to give a government with a relatively modest defense budget reason to reconsider the project.

Interestingly, while the Canadians were working on the Arrow, the Americans were working on a conceptually similar long-range, high-performance interceptor, the North American "F-108 Rapier". The Rapier never got beyond the mockup stage, being canceled in September 1959. The Americans did continue work for a time on a Mach 3 interceptor design, the Lockheed "YF-12A", derived from the SR-71 reconnaissance aircraft, but though prototypes were flown it, too, was canceled. The strategic threat had shifted to ICBMs, and an expensive Mach 3 interceptor was simply not worth the cost. Whatever the facts of the case, it is hard not to sympathize with those who dream of the CF-105 thundering on patrol over Canada's snow-covered north.

* It seems that a number of nonflying CF-105 replicas have been built for museum displays, including at least one full-scale replica built by a Canadian named Allan Jackson that was used in the Dan Ackroyd movie; that replica was cut up at the end of the film and the owner got it back in pieces, much to his distress. Apparently there had been a miscommunication and Jackson was compensated for the bungle, but it took him some time to get the replica back into shape again. It has since had other ups and downs. Work is underway to build a subscale flying replica, which would certainly be an interesting airshow demonstrator.

BACK_TO_TOP* There's really not that much interest in the CF-100, but there is a faction of Canadians that are still flogging CF-105 conspiracy plots. The enthusiasm for the Arrow at least has led to more interesting creativity than conspiracy theories, with artwork produced of "what if" Arrows, such as nuclear strike or electronic warfare variants. Other concepts have focused on follow-ons, with features such as modified wings and canards.

* Sources include:

* Illustration credits:

* This document was originally only on the CF-100; in 2022, I added a document on the CF-105 Arrow that I'd originally written in 1997. That gives the revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 jun 05 / Originally only on CF-100. v1.0.1 / 01 may 07 / Review & polish. v1.0.2 / 01 apr 09 / Review & polish. v1.0.3 / 01 oct 10 / Review & polish. v1.0.4 / 01 sep 12 / Review & polish. v1.0.5 / 01 aug 14 / Review & polish. v1.0.6 / 01 jul 16 / Review & polish. v1.0.7 / 01 jun 18 / Review & polish. v1.0.8 / 01 apr 20 / Review & polish. v2.0.0 / 01 mar 22 / Added in CF-105, new illustrations. v2.0.1 / 01 feb 24 / Review & polish.BACK_TO_TOP