* In the last decades of the Cold War, most of the major players in the drama began programs to develop "fourth generation" air-superiority fighter aircraft. Since the cost of such leading-edge machines was painful, a number of European nations decided to collaborate on development of what would become known as the "European Fighter Aircraft", or simply "Eurofighter", along with the more colorful name of "Typhoon". The end of the Cold War meant that the need for a fourth-generation fighter was not as great as it had been, but the Eurofighter program continued, if with delays and changes in direction, and Europe's premier fighter is now in service. This document provides a history and description of the Eurofighter Typhoon.

* In the late 1970s, a number of European air forces were confronted with the fact that their fighter fleets were beginning to seem outdated in the face of new American machines, such as the F-15 and F-16, and more to the point new Soviet fighter designs, such as the MiG-29 and Su-27. These hot new machines would certainly be followed by even hotter designs, and so the Europeans had to keep pace.

By 1977, the West Germans were considering a replacement for their Lockheed F-104 Starfighters, while the French were thinking about a replacement for their SEPECAT Jaguar strike fighters, and the British were interested in a replacement for both their Jaguars and British Aerospace (BAE) Harrier "jumpjet" strike fighters. The British wanted their replacement aircraft to be low-cost, but also to have much better air-to-air combat capabilities than the Jaguar or Harrier. In addition, the British wanted jumpjet capabilities like those of the Harrier, or at least good short / rough field performance. The British had become used to working with international collaborations to develop new combat aircraft, and cast about for partners. In the meantime, the British also conducted a series of small-scale technology-demonstration programs to help develop useful subsystems for such a new aircraft.

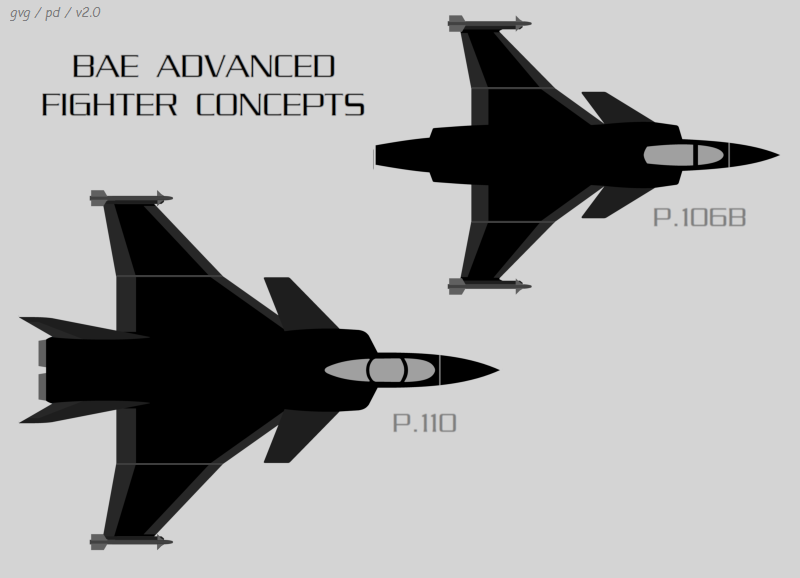

The British rethought their priorities after analysis showed their requirements were too ambitious for a single aircraft. They then specified two different aircraft, including a Jaguar replacement with good air-to-air combat capabilities, designated the "Air Staff Target (AST) 403"; and a short-takeoff Harrier replacement, designated the "AST 409". The AST 409 requirement would lead to purchase of the improved US-designed Harrier II and, eventually, towards the US F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, but that's another story. The AST 403 specification led BAE through a number of design concepts, including the heavyweight twin-engine "P.110" and the lightweight single-engine "P.106B", with the P.106B being preferred.

In the meantime, Messerschmitt-Boelkow-Blohm (MBB) in Germany was considering a number of different concepts for an air-superiority fighter under the Luftwaffe's "Taktisches Kampfflugzeur 1990 (TKF-90 / Tactical Combat Aircraft 1990)" requirement. BAE and MBB then began to discuss a collaboration, resulting in 1979 in a proposed design for a "European Collaborative Fighter (ECF)", later the "European Combat Aircraft (ECA)". The ECA resembled the MBB TKF-90 design.

Dassault of France was also generating a number of advanced fighter designs, but did little to tell anyone else about them; the French position was that if they were going to be in an international collaboration, they would be in the driver's seat. The French attitude led to the collapse of intergovernmental talks on collaboration in 1980. The British government canceled AST 403 in 1981, while the West German government showed no interest in funding development of the TKF-90. That might have been the end of the whole thing, but BAE management realized that European air forces would need a new fighter sooner or later, and pressed on. BAE had been working on an export fighter-bomber design, the "P.110", basically a follow-on from the P.106B concept with ECF influence, but couldn't find a buyer to fund production.

However, BAE was able to inspire the Anglo-German-Italian Panavia consortium, which had built the Tornado multi-role combat aircraft, to collaborate on another machine, the "Agile Combat Aircraft (ACA)", which was based on TKF-90 and P.110 concepts. The Italians were very interested in the ACA, since they had an urgent need for a replacement for their F-104 Starfighters. A mockup of the ACA was displayed at the Farnborough Air Show in the UK in 1982 and at the Paris Air Show in 1983.

As an answer to the ACA initiative, the French committed to develop a fourth-generation fighter of their own, under the "Avion de Combate Experimentale (ACX)" program, which would become the Dassault Rafale. The British were perfectly happy to have the French go their own way, since the French had shown a clear tendency to short-change the British in other aircraft collaborations. The West German government, however, was very keen on political alignment with the French, the British being seen as too heavily tilted to the American point of view for Continental tastes, and the Germans had misgivings about the ACA program.

In any case, ACA went ahead for the moment, with plans generated for the production of two demonstrators under the "Experimental Aircraft Programme (EAP)" -- if building a new fighter seemed to be taking time, production of acronyms was at full steam. On 26 May 1983, the British Ministry of Defense awarded BAE and Aeritalia, the Italian partner, a contract for one of the EAPs, and the expectation was that the Germans would quickly commit to construction of the second demonstrator.

BACK_TO_TOP* MBB wanted to go ahead with the second demonstrator, but the West German government had no interest in funding it. They didn't want to antagonize the French by throwing their lot in with the British and Italians; similarly did not want to antagonize the British and Italians by throwing in with the French; and accordingly decided that sitting on their hands the best option for the moment. That effectively killed the ACA program as such, but BAE resolutely went ahead with the construction of their EAP demonstrator. The demonstrator was built with help from Aeritalia and some low-key assistance from MBB, which was still interested in the project even if the West German government wasn't keen.

As it emerged, the EAP demonstrator featured the cranked-delta / canard-delta configuration of the various concepts that led up to it, but differed from them in having a single tailfin instead of twin tailfins. That was because MBB had been expected to provide the rear fuselage elements of the EAP, but when their funding was cut, BAE simply used the rear section of a Tornado, including the tailfin. The EAP also used the Tornado's twin TurboUnion RB.199 afterburning bypass jet engines. The intakes were placed under the belly, and had a hinged panel on the lower lip that could be dropped open to ensure airflow at high angles of attack.

This rear section was made mostly of aircraft alloys, but the rest was mostly graphite-epoxy composite assemblies, leading jokers to call it the "plastic plane". It also incorporated a quadruple-redundant fly-by-wire (FBW) flight control system (FCS) -- which was a necessity, since the EAP demonstrator was "dynamically unstable", meaning it would quickly go out of control unless computers performed tiny flight adjustments at all times. Dynamic instability helped give the aircraft high agility, though it required many lines of tricky software.

The EAP demonstrator featured a "glass cockpit", with three Smiths Industries "multifunction displays (MFDs)" using color picture tubes; a GEC-Marconi wide-angle "head-up display (HUD)"; and center-mounted "hands on throttle and stick (HOTAS)" controls. BAE also included a voice-warning system, and the company tinkered with a "direct voice input (DVI)" command system. Test pilots had been part of the design team for the cockpit layout, and the result was regarded as outstanding.

The EAP demonstrator performed its first flight on 8 August 1986 and conducted 259 test flights up to its retirement on 1 May 1991. Pilots were wildly enthusiastic about the machine, one of them saying: "It goes like a ferret with a firework up its bum!" It was fast, it was agile, and it was great fun to fly.

There was comment at the time and afterward that Britain should have simply picked up the EAP demonstrator and run with it, and in fact BAE had been promoting an operational fighter that leveraged off the demonstrator to the British Royal Air Force (RAF). However, it simply wasn't going to happen. The British government made it perfectly clear they didn't want to pick up the entire tab for a new fighter, and so any such new aircraft would have to be produced by an international collaboration. In fact, such discussions had led to decisions on collaboration even before the first flight of the EAP demonstrator. In hindsight, it remains an open question, one very hard to answer, as to whether the UK would have been better off to go it alone.

BACK_TO_TOP* Beginning in late 1983, the air staffs of five European nations -- Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain -- began to work together to define specifications for a common fourth-generation fighter aircraft, to go into service in the mid-1990s. By early 1985, Britain, West Germany, Italy, and Spain had settled on a design along the lines of the EAP demonstrator, in construction at the time, while the French were insisting on an aircraft derived from the "Rafale A" demonstrator. The French position was just as blunt as it had been before: France would be in the driver's seat, the aircraft would be a French design, built by a consortium with Dassault at the head and France as the absolute majority partner. Dassault would essentially parcel out such subcontracts as deemed necessary.

The friction may have been at least partly due to miscommunication. Nobody could have objected much if the French said they were working on a program of their own and invited risk-sharing partners to sign on; modern international aircraft programs are often organized in such a way. However, if everyone else was thinking in terms of a collaboration in which they had a more or less equal say, the French attitude was a non-starter, to put it mildly. A British official dryly commented: "One wonders what France would have demanded had it not been interested in collaboration and had it simply wanted to put us off the idea." Over the course of the last half of 1985, the French and the other nations involved in the discussions parted ways, though the West Germans were not happy about dropping the French from the proposed partnership.

Although Britain and Spain wanted a multi-role fighter, West Germany and Italy were only interested in an air-superiority machine. The group managed to hammer out their differences, with a general agreement on specifications reached in December 1985. A formal specification for the "EFA (European Fighter Aircraft)" was released in September 1987, with production expected to begin in 1992. As it turned out, this was short of the mark by a decade.

* The EFA was focused on air superiority, but could perform ground attack as a secondary mission. It was to have high performance, high maneuverability, and have docile handling characteristics. It was also to have a low "radar cross-section (RCS)" and be capable of operating from short forward airstrips. A formal development contract was awarded to the "Eurofighter" consortium on 23 November 1988, specifying delivery of eight prototypes.

The principal manufacturers in the consortium were, in order of workshare: BAE Systems of the UK (33%); MBB (later DASA) of Germany (33%), Aeritalia of Italy (21%); and CASA of Spain (13%). DASA and CASA later became part of the EADS aerospace group, now the Airbus group, while Alenia eventually became a component of the Leonardo group.

The "EJ.200" engine for the new fighter was to be developed by the parallel "EuroJet" group, which includes Rolls-Royce, MTU, Fiat Avio (now part of Leonardo), and SENER (now ITP) of Spain. The EJ.200 is an evolution of the RB.199, derived from the Rolls-Royce "XG40" demonstrator engine built in the early days of the Eurofighter program. The EJ.200 was to provide better performance and feature 30% fewer parts than the RB.199.

Despite these decisions, the program remained muddled. The West Germans raised a number of major objections, for example proposing that the new fighter use an improved version of the AN/APG-65 radar used on the US F/A-18 Hornet instead of a European solution; and suggesting, for reasons nobody else could understand, that early development aircraft use General Electric F404 engines instead of the TurboUnion RB.199. The manufacturers involved with the program didn't begin "cutting metal" for the initial prototypes until 1989.

* By 1991, everything finally seemed to be going smoothly, leading a BAE official to comment: "We are now comfortable in bed with Italy, Spain, and even Germany. It's not a bed of roses, but France isn't even in the boudoir, so we have a sporting chance of making it work."

Then everything went to hell again. The Cold War was over, Germany was re-united. The threat that the Eurofighter had been originally intended to meet had evaporated, though as it would turn out new threats would raise their ugly heads only too soon, and German reunification was proving painfully expensive. 1992 was an election year in Germany and many of the voters were pacifistic, with a strong aversion to weapons programs.

The Eurofighter became politically controversial, with the German government teetering on the edge of pulling out of the project. The Germans raised such a fuss -- forcing the consortium to go in circles to find cost-saving design changes for the aircraft -- that the other partners seriously considered just telling them to go, and be done with it. However, though German politicians were making hostile noises about the Eurofighter, Luftwaffe brass insisted that they needed the aircraft, and that it was the aircraft they needed.

In fact, although studies were performed to investigate purchase of a more-or-less "off the shelf" solution for the Luftwaffe, covering the range from the McDonnell Douglas F-15 to the SAAB Gripen to the Mikoyan MiG-29, the studies demonstrated that no other existing aircraft was as cost-effective. That was not too surprising, since the Eurofighter had been originally designed to meet the specifications of the air forces of the member nations. Attempts to define a cheap-and-dirty version of the Eurofighter led to a similar result: a cheaper machine could be built, but it wouldn't do the job.

The insistence of the British and Spanish on a multi-role capability was important to the machine's survival. The fall of the Soviet Union greatly changed the nature of the challenge faced by European nations -- from a sullen Communist monolith to the East, to unpredictable brushfire conflicts that could spring up almost anywhere. A multi-role Eurofighter fit the new challenges well.

* In the end, after a great deal of fuss, Germany stayed in the group. The fighter was redefined somewhat to decrease costs in principle, with some high-budget elements made optional, but the general belief was that the whole squabble had led to a more expensive aircraft, and the "savings" were merely political smoke-and-mirrors. The redefined aircraft was redesignated the "Eurofighter EF2000" as a means of glossing over the fact that the original plan envisioned that it should have been in production in 1992. The delays were painful to the Italians, who desperately needed a replacement for their Starfighters, and as an interim solution they leased 24 Tornado F.3 interceptors from the Panavia group.

The dust settled and work on the prototypes went ahead. The first prototype Eurofighter, designated "DA1", finally flew on 27 March 1994. That prototype was built by DASA, wore Luftwaffe markings, and was flown by German pilot Peter Weger from an airfield at Manching, Germany. There were no doubt some who questioned the justice of letting the Germans have the honor of the first flight -- all the more so because the German government continued to short-change the program, not committing to proper funding until 1995, and waffling on for two more years after that. However, it made sense in terms of keeping a happy home, and in any case both MBB / DASA and the Luftwaffe had been made at least as miserable as everyone else. The Germans didn't give much fanfare to the initial flight, possibly on the judgement that there was no sense in antagonizing their partners further.

BACK_TO_TOP* The eight prototypes originally planned were built, including:

The formal decision to go ahead with production was made in 1997, with production contracts awarded in 1998. In September 1998, the Eurofighter organization announced the aircraft's name of "Typhoon". This name was assigned for export aircraft, and the organization stressed that member nations would be free to name it what they liked. However, Typhoon was a good choice for a name, since it was assigned to historically important British and German aircraft, and the word itself is derived from Japanese and so reflects no linguistic bias among the Eurofighter group member nations. It doesn't appear that any of the users made much of a fuss about the name "Typhoon", and it certainly had a lot more snap than "Eurofighter".

Since the aircraft was still not in production, much less operational service, by the year 2000, the various factions involved in the effort gradually began to refer to the aircraft as simply the "Eurofighter" and not the "Eurofighter EF2000". Despite all the problems and delays -- which were not unique to the Eurofighter among the fourth-generation fighter efforts, and to an extent were inevitable in a multinational collaboration -- the result proved no disappointment.

* As it emerged, the Eurofighter was a canard-delta aircraft, powered by twin Eurojet EJ.200 two-spool afterburning bypass jet engines, with the intakes on the belly of the aircraft under the cockpit. This position helped ensure airflow at high angles of attack. The arrangement was similar to that used on the EAP demonstrator, except that the Eurofighter's intakes curved up across the belly, while the EAP demonstrator's intakes had a straight rectangular cross-section. The hinged lower lip used in the EAP demonstrator was not carried over to the Eurofighter.

Each EJ.200 engine provided 60.0 kN (6,120 kgp / 13,490 lbf) dry thrust and 90.1 kN (9,185 kgp / 20,250 lbf) afterburning thrust. The first two prototypes were initially powered by RB.199 engines. The Eurofighter was also fitted with an auxiliary power unit (APU) for self-starting and ground power.

Unlike the EAP demonstrator, which had a compound-delta wing, the Eurofighter had a simpler cropped-delta wing. The trailing edge was straight and featured full-span split "flaperons (flap-ailerons)". There were small strakes on the fuselage below the cockpit, as well as above and behind the canard fins to make sure that airflow over the wing remained effective at high angles of attack. The canard fins were of "all-moving" configuration and had a strong anhedral droop. The straight-edged tailfin also differed from the curved Tornado tailfin used on the EAP demonstrator. There was a large dorsal airbrake behind the cockpit.

The landing gear featured a nosewheel mounted under the air intakes and retracting backwards, and main gear pivoting from the wings to retract into the fuselage. All gear had single wheels. A brake parachute was stored in a housing at the base of the tail, and there was a retractable inflight refueling probe on the right side of the nose.

The airframe was built of about 50% composite materials by weight and about 70% by surface area, with substantial use of titanium and lithium-aluminum alloys elsewhere. Although comparable in dimensions to the Panavia Tornado, the Eurofighter had an empty weight only about 70% as great, while being more capable in almost all regards. The advanced construction techniques also reduced the parts count of the airframe, with the Eurofighter having about 16,000 structural elements to 36,000 for the Tornado. Maintenance was greatly reduced as well, with the cost of maintenance for the Typhoon estimated at 25% of total life-cycle cost, compared to almost 50% for the Tornado.

The Eurofighter had a greater RCS than the US F-22 or F-35, though radar-absorbent material was used in the inlets and around the cockpit, and the composite assemblies were designed with an eye towards reducing RCS.

___________________________________________________________________

EUROFIGHTER TYPHOON:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

10.95 meters (35 feet 11 inches)

wing area:

50.0 sq_meters (538.2 sq_feet)

canard wing area:

2.40 sq_meters (25.83 sq_feet)

length:

15.96 meters (52 feet 4 inches)

height:

5.28 meters (17 feet 4 inches)

empty weight:

10,995 kilograms (24,245 pounds)

loaded weight:

23,000 kilograms (50,715 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

Mach 2+

service ceiling:

16,765 meters (55,000 feet)

take-off run:

700 meters (2,300 feet)

combat radius:

1,390 kilometers (865 MI / 750 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

Of course, the Eurofighter featured a modern "glass cockpit", with color flat-panel MFDs; a wide-angle HUD; and HOTAS flight controls. The pilot sat on a Martin-Baker Mark 16A "zero-zero (zero altitude, zero speed escape)" ejection seat, under a frameless clamshell canopy. The back-seater in the two-seat version sued the same control layout as the pilot, but with a "HUD repeater" instead of a HUD, and of course sat on the same type of ejection seat.

The Eurofighter had a built-in 27-millimeter Mauser cannon on the right side of the belly of the aircraft, with 150 rounds of ammunition. The RAF originally chose to ignore the cannon, not stockpiling ammunition nor using in training, but eventually decided it was useful after all. The aircraft had four semi-recessed fuselage stations for air-to-air missiles (AAM), plus a centerline stores pylon and four stores pylons under each wing, for a total of nine stores pylons. The centerline pylon and a single pylon under each wing were "wet", permitting carriage of external fuel tanks.

Maximum external stores load was a hefty 8,000 kilograms (17,640 pounds). In practice, combat aircraft do not as a rule carry anywhere near their maximum stores load in operational service; one might guess that a representative stores load for a Eurofighter might be about half that. Possible stores included:

The Eurofighter's combat avionics were built around the "Captor" (previously ECR-90) pulse-Doppler multimode radar. This radar was selected after the long debate with the Germans on whether to use a European radar design, or an improved version of the US Hughes AN/APG-65. Captor was developed by the "EuroRadar" consortium, which had a varied and evolving membership that defies useful description.

Captor was derived from the "Blue Vixen" radar fitted to the BAE Sea Harrier FA.2. It featured a mechanically-scanned antenna -- leading to the label of "Captor-M" when derivative variants were introduced -- and its capabilities included:

The radar was complemented by an "infrared search and track / forward-looking infrared (IRST / FLIR)" sensor, mounted just to the left of the front of the cockpit. This sensor was designated the "Passive Infra-Red Airborne Tracking Equipment (PIRATE)", and was a very capable piece of gear. As an IRST, it could scan while tracking and ranging multiple targets, and as a FLIR, it provided a selectable wide-angle or narrow-angle field of view, with the optics directed by the pilot's helmet-mounted sight. A full PIRATE implementation was not provided in initial production, with early machines updated later.

The Eurofighter included a "Defensive Aids Sub-System (DASS)" built by the "EuroDASS" consortium. The Germans pulled out of the consortium due to significant cost increases in DASS, and for a time Luftwaffe Eurofighters weren't even going to have a countermeasures suite. That was an impractical decision, driven entirely by politics, and the Germans rejoined in 2001.

As with PIRATE, a complete DASS was not available in early production. In full development, DASS featured threat-warning systems and active countermeasures; it was fully automated, allowing it to detect, identify, and prioritize threats, as well as take countermeasures automatically. DASS was fully integrated with the Eurofighter's avionics systems. DASS elements included:

Finally, the Eurofighter was fitted with the "Link 16 Multifunctional Information System (MIDS)" datalink, though again this item wasn't available at the outset. All avionics were integrated by six digital buses, including two fiber-optic buses. The digital flight control system was designed in levels, with early Eurofighters featuring simple functionality, and improved functionality added in stages.

BACK_TO_TOP* The first production standard Eurofighter, a two-seater, performed its initial flight on 5 April 2002, and was followed within days by two more production aircraft. Initial delivery of a production aircraft (to Spain) was in September 2003. An experienced RAF pilot summed up the reaction to the machine: "When I was introduced to the F-15 [Eagle], it represented a quantum leap forward from my beloved [English Electric] Lightning -- but the quantum leap I experienced going from Lightning to Eagle was repeated when I began my involvement with Typhoon."

Pilots reported that the Typhoon was not merely fast and powerful, it was also incredibly agile. Despite the agility and inherent instability, it was not all that challenging to fly, due to the very intelligent FCS -- which also provided automatic spin and stall recovery capabilities. The cockpit layout was very intelligent as well, a clean sci-fi arrangement with rationalized displays and control inputs, a far cry from the era of "steam plant" fighter instrument panels of the Lightning and its contemporaries. As a Luftwaffe pilot commented:

BEGIN_QUOTE:

[The Typhoon] is the most powerful combat aircraft in Europe, and its carefree flight handling characteristics are brilliant. The flight control system makes sure the aircraft can't be put outside of its envelope, so I can concentrate 100% on operating it as a weapons system.

END_QUOTE

The Eurofighter is now in service with all four Eurofighter member nations. Each air force is obtaining aircraft from local manufacture:

Although each nation's Eurofighters are being delivered from a different manufacturer, in fact the construction of sub-assemblies is parceled out between the different companies. It was recognized in earlier cooperative programs that full duplication of production at manufacturing sites in each member nation was absurdly wasteful. In essence, factories in each Eurofighter member nation provide parts for a "kit", in the form of major sub-assemblies; each factory then obtains all the sub-assemblies and fits them together. The sub-assemblies are designed in a modular fashion to ensure that they can be pieced together with relative ease.

* There have been sales outside of the "Big Four":

Other deals didn't pan out. The Dutch also considered the Eurofighter, but went with the US F-35 instead; the Eurofighter lost out in a South Korean competition against the Boeing F-15K; and Singapore dropped the Eurofighter from a competition for a heavy fighter, leaving the Rafale and F-15 to fight it out, with the F-15 winning in the end.

The first combat action of the Typhoon took place in 2011, with the NATO intervention in the Libyan Revolution that ousted Libyan dictator Moammar Qaddaffi. Typhoons cooperated with RAF Tornados in air strikes against Libyan loyalist forces, with the Tornados performing "buddy designation" of targets for the Typhoons -- the Typhoon force not being quite up to speed on self-designation at that time. From late 2015, RAF -- and Saudi -- Typhoons participated in strikes against Islamic State insurgents in Syria. Saudi Typhoons also performed strikes in the course of the country's war in Yemen.

From 2012, Typhoons have participated in large-scale North American training exercises such as RED FLAG, with the Eurofighter demonstrating a clear edge over F-15 and F-16 fighters, and at least matching the US Air Force's premier F-22 Raptor. The 400th Typhoon was delivered in late 2013, with the program continuing to advance -- after its protracted and rocky start.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Eurofighter was originally introduced with minimal capabilities, to be updated in a series of block revisions. The blocks were segments in a set of production "Tranches":

The Saudi Eurofighters were based on Tranche 2. Tranche 1 machines could not be brought up to full Tranche 2 standard, but they were updated via the "R2" program to the extent it was possible to do so. The RAF, as mentioned, obtained a strike capability for their Tranche 1 machines.

A total of 148 Tranche 1 machines was delivered:

In 2017 the Austrians, having found their Eurofighters unsatisfactory, announced they would be phased out from 2020. They claimed their Tranche 1 machines were too limited and difficult to upgrade; they went so far as to sue the consortium in 2017 for fraud in the sale of the aircraft. Consortium officials replied that the Austrians had obtained the aircraft stripped of significant systems to cut costs, and so it was ironic that the Austrians then complained they didn't have everything they wanted. They added that Tranche 1 Eurofighters were reasonably upgradeable, and were perfectly adequate for the air-defense role -- which is what the Austrians obtained them for. The RAF had considered early retirement of their Tranche 1 machines and decided they were worth hanging on to. An Austrian appeals court dismissed the lawsuit in 2020, saying in effect that the Austrian government didn't have a case.

A total of 299 Tranche 2 machines was delivered:

Of course, following Tranche 2, work began on a "Tranche 3". Difficulties in coming up with a solid definition led to splitting Tranche 3 into "Tranche 3A" and "Tranche 3B". First flight of a Tranche 3A machine was in late 2013, with final deliveries in 2020. Elements included:

The Kuwaiti, Omani, and Qatari machines were in Tranche 3A configuration, giving deliveries and orders for 176 Tranche 3A machines:

The Kuwaiti and Qatari Typhoons were delivered with the Captor-E ECRS Mark 0 AESA radar. The Kuwaitis also ordered Lockheed Martin Sniper targeting pods for their Typhoons, these being the first Typhoons to carry that item.

Tranche 3B was effectively abandoned -- but in 2020, the German government decided to sell off the Luftwaffe Tranche 1 machines and buy 38 new Eurofighters under the "Quadriga" program. Of course, they will be up to the latest spec, with the "Captor-E ECRS Mark 1" radar, an improved Mark 0. Airbus, after thinking it over for a while, decided to call them "Tranche 4" machines. Spain also decided to buy 20 Tranche 4 machines -- following that up in 2023 with an intent to buy 25 more, either in Tranche 4 or a possible "Tranche 5" configuration. That gave total deliveries and orders to date of 148 + 299 + 176 + 83 == 705 Typhoons:

That is well lower than what was envisioned at the outset, quantities being gradually reduced all through the program. However, more Eurofighters will be built. The Germans have a requirement for a new Electronic Combat Reconnaissance (ECR) / Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD) to replace their Panavia Tornado ECR machines, with an ECR-SEAD version of the Eurofighter seen as a possible solution. However, this was complicated by the fact that the Tornados were a nuclear strike asset -- Germany has nukes under a dual-key arrangement with the USA -- and the Eurofighter is not qualified for nuclear strike.

Nonetheless, in 2022 the Germans indicated they were moving ahead on the Eurofighter ECR / SEAD variant, which was labeled the "Eurofighter Elektronischer Kampf (EK)", or rendered in English as "Eurofighter Electronic Warfare (EW)". As far as the nuclear strike role goes, the Germans would like to acquire F-35s.

Incidentally, Britain's RAF has a set of designations for their Eurofighters:

The Spanish have given their Typhoons the designation of "C.16".

* Typhoons in service are being continually upgraded. They get ongoing tweaky "Performance Enhancements (PE)", particularly in software. Both Germany and Spain plan to update their Typhoons with the Captor-E Mark 1 radar fitted to their Tranche 4 machines, while the British RAF wants to obtain a new "Captor-E ECRS Mark 2" radar for their Typhoon, well more sophisticated and powerful than the ECRS Mark 0/1. Italy is collaborating with Britain on the ECRS Mark 2; in-service date is expected to be 2030.

Eurofighter users are working to expand the Typhoon's weapons capabilities, the British effort being known as "Project Centurion", known as the "Phase 3 Enhancement (P3E)" effort to the Eurofighter group. All RAF Typhoons were brought up to P3U standard, able to employ Brimstone, Storm Shadow, Paveway IV, and BVRAAM, along with support for the Litening targeting pod; a triple-store rack was eventually developed for Brimstone carriage. Those single-seat Typhoons more or less dedicated to the strike mission became FGR4s. Other users, who have adopted different stores, are pursuing their own qualifications, though obviously there is some leverage between them.

The British and French are now collaborating on a "Future Cruise / Anti-Ship Weapon (FC-ASW)" to replace the British Storm Shadow standoff missile and SCALP, its French counterpart, as well as Harpoon and Exocet antiship missiles in British and French service respectively. It will be carried on British Typhoons and French Rafales, and will also be adapted to surface launch. It is still in early development, with no schedule available yet.

In May 2019, the Eurofighter consortium began the Eurofighter "Long-Term Evolution (LTE)" program to enhance the airframe and engines. It will feature smarter and more capable electronic warfare systems; improved datalink connectivity; updated cockpit environment, with a large central display; flexible power and cooling technology; and EJ200 engines with more thrust, reliability, serviceability, and survivability.

LTE also involves an "Aerodynamic Modification Kit (AMK)", with tweaks such as strakes and improved trailing-edge flaps to improve agility, with the enhancements easily retrofitted to older machines. Another enhancement is an increase in the loadout of AAMs, previously limited to eight, by adding dual stores racks.

BACK_TO_TOP* Early versions of this document tried to give a blow-by-blow description of the gradual level of upgrades to the Typhoon in service, but that turned out to be both confusing and very hard to nail down. I finally decided just to give general descriptions of the tranches, and not worry about the incremental block evolution of each tranche. I took a similarly broad-brush approach to upgrades.

* Sources include:

The Eurofighter website was also consulted for current news items.

* Illustrations credits:

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 aug 02 v1.0.1 / 01 aug 04 / Review & polish. v1.0.2 / 01 jul 06 / Review & polish. v1.0.3 / 01 nov 06 / Review & polish. v1.0.4 / 01 nov 08 / Review & polish. v1.0.5 / 01 oct 10 / Simplified tranche comments. v1.0.6 / 01 sep 12 / Combat in Libya. v1.1.0 / 01 jan 14 / Clarifications on tranches & production quantities. v1.1.1 / 01 dec 15 / Review & polish. v1.1.2 / 01 nov 17 / Review & polish. v1.1.3 / 01 oct 19 / Review & polish. v1.2.0 / 01 sep 21 / Review & polish. v1.3.0 / 01 sep 23 / Review, update, & polish. (**)BACK_TO_TOP