* One of the great dreams of a number of aircraft designers of the 1940s was the "flying wing", an aircraft that consisted only of a wing, providing pure aerodynamic efficiency. The most famous of the flying wings was the series of test machines and heavy bomber prototypes built by Jack Northrop. This document provides a history and description of the Northrop flying wings, as well as the German Horten flying wings. A list of illustration credits is given at the end.

* John Knudson "Jack" Northrop was born in Newark, New Jersey, on 10 November 1895. His family decided to move West, and spent time in Nebraska, which Jack regarded as "dreary", being too flat, too cold or too hot, and dull -- before moving on to Santa Barbara in South California.

In 1916, Jack Northrop began to visit a local automotive shop run by the brothers Allan and Malcolm Loughead (pronounced "Lockheed"). The Loughead brothers were also tinkering with building airplanes in their shop, and Northrop was interested enough in what they were doing to be hired on. The Loughead brothers had very little formal education, and Northrop's knowledge of algebra and physics made him useful.

After America declared war on Germany in 1917 Northrop enlisted, but the Army put him to work helping build flying boats instead of sending him into action. He mustered out in 1918, went back to working for the Loughead brothers at their plant in Burbank, California, in the Los Angeles area. He also married his high-school sweetheart.

Northrop was intrigued when he learned that the German Albatros fighter had a fuselage made of molded plywood, instead of the wood-and-canvas frame common to aircraft at the time. As a result, Northrop's first airplane, the "Loughead S-1", was built using plywood that had been soaked and forced into a concrete mold with a balloon, resulting in smooth curves instead of the boxy lines of most contemporary aircraft. However, the market for new aircraft was lousy, and the Loughead company closed its doors in 1920.

Jack Northrop worked for his father's building company for three years as an architectural draftsman, but that company folded, too. He then worked for another little aircraft firm, run by Donald Douglas, helping the company build the World Cruiser Aircraft for the US Army, which would fly it around the globe in the spring and summer of 1924.

The World Cruiser Aircraft was of entirely conventional design. Northrop had a strong innovative streak and wanted to do more, coming up with ideas for a streamlined aircraft with a single wing. There was no way it would happen at Douglas, but Northrop was still in touch with Allan Loughead. Loughead had gone on to work as a real estate developer but wanted to get back into aviation, and he had potential backing from a Los Angeles venture capitalist named Fred Keeler. With Northrop's design in hand, Loughead was able to get the financial backing from Keeler to start a new company. Keeler, however, not unreasonably insisted that the outfit be named the "Lockheed Aircraft Company" to prevent everyone from stumbling over the pronunciation and spelling of "Loughead".

The new company set up in a rented shop in Hollywood in 1926. The first "Vega", as the new aircraft was called, was ready to fly by mid-1927. It looks quaint today, though still elegant in a classic sort of way, but it was breathtaking then: all smooth curves except for the radial engine up front, fixed landing gear in teardrop-shaped spats, and a solid high-mounted wing. The wing was unbraced, which made Loughead very nervous, feeling that nobody would think the aircraft was safe. He tried to push Northrop into adding struts, but Northrop stubbornly held out.

* Northrop proved right: the good looks and superior performance of the Vega made it a runaway success. It won air races; it was used by aerial superstars such as Amelia Earhart and Wiley Post to set records; and, more practically, it was a neat and fast six-passenger airliner. Through 1928 and 1929, the Lockheed Company could hardly keep up with orders.

Northrop had plenty of clout in the company, and was thinking of improved derivatives of the Vega with aluminum instead of wood construction, refined streamlining, and other new features. However, he had a bigger vision in mind as well: a flying wing. He had grown up in Santa Barbara watching seagulls and similar soaring seabirds glide through the sky, and found an inspiration in their configuration: mostly wing, a minimal body. What could be more efficient than an airplane that consisted of nothing but a wing? It would be capable of great range and load capability, since there would be nothing in the design of its airframe that would not contribute to lift. If seagulls could more or less do it, so could he.

Hugo Junkers in Germany was also interested in the concept of the flying wing and was struggling with designing one that could fly and be controlled. Allan Loughead, unfortunately, was not a believer, and the company had also hired on a manager who didn't give Northrop a free leash. Northrop only put up with that awkward arrangement for a few weeks and then quit.

George Hearst, son of publishing baron William Randolph Hearst, had bought a Vega, and the senior Hearst proved perfectly willing to back Northrop in his proposed ventures. Northrop established his own company, the Avion Corporation, sited in Burbank, and went ahead with his ideas for a flying wing, and for a Vega follow-on built of aluminum named the "Alpha" -- in that order.

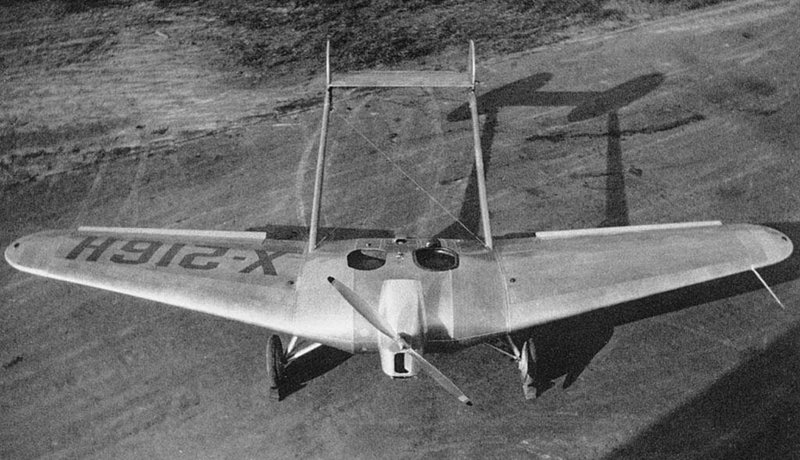

Northrop's first shot at a flying wing had a wingspan of 9.15 meters (30 feet) and a single engine with 65 kW (90 HP). "The Wing", as it was known, was built of metal, had fixed "reverse tricycle" landing gear, and twin open cockpits, though the right cockpit was usually faired over; the pilot didn't have a windscreen, the belief being that it would interfere with streamlining. Northrop quickly realized that he was in unfamiliar territory and that the flying wing was nearly uncontrollable, so he added a twin-boom tail. It was powered by a Menasco Pirate four-cylinder inverted inline air-cooled engine providing 67 kW (90 HP), originally driving a fixed two-blade pusher propeller through a driveshaft. The prop was later moved to the nose.

First flight was in 1929, with freelance pilot Eddie Bellande at the controls; the take-off was from Burbank airport, but the landing was at Muroc Dry Lake, in the California desert. The aircraft was never given a formal name, being known as the "Northrop 1929 Flying Wing". Apparently it was scrapped.

That taken care of -- at least for the moment -- Northrop then turned out the Alpha, which performed its first flight in March 1930. It was sold as a mail carrier, and there were few buyers; only 17 were built, since the Depression was setting in and things were difficult. Northrop considered a partnership with an aircraft firm in Kansas City, though he was very reluctant to move back to the Great Plains, and decided instead to cut a deal with Donald Douglas to set up a "Northrop" subsidiary of Douglas Aircraft in 1932. He helped Douglas create the groundbreaking DC-2 and DC-3 airliners.

That was a satisfying accomplishment, and Northrop should have been happy with his life. His home life with his wife and three kids was stable and comfortable, and he was respected in his work, both for his clear abilities and for his modest and conscientious management style. However, he still wanted more, wanted to be his own boss. Douglas bought out Northrop's share in the Douglas Company in 1938, turning the Northrop subsidiary into the Douglas El Segundo Division. Northrop decided to strike out completely on his own, using the cash and some additional backing from financier LaMotte Cohu to establish Northrop Aircraft INC in 1939. With war coming, business was good, with Northrop winning foreign aircraft sales and contracts to build subassemblies for other aircraft manufacturers.

BACK_TO_TOP* Northrop's real focus in his own company was the flying wing. Working with Theodore von Karman of Caltech, arguable the most prestigious aerodynamics expert in the US, in 1940 Northrop flew his first true flying wing, the "N-1M", with "M" standing for "Mockup". Its initial flight was on 3 July 1940, with freelance test pilot Vance Breese at the controls.

The "Jeep", as the N-1M was nicknamed, was made of steel tubing and sheathing so it could be easily modified, and in fact its airframe configuration could be altered to an extent by ground crew adjustments. It had retractable tricycle landing gear -- all single wheels, the nose gear retracting backward and the main gear retracting from the wings in toward the fuselage -- and was powered by twin Lycoming O-145 flat-four air-cooled engines with 48 kW (65 HP) each, driving three-bladed variable-pitch pusher propellers. The aircraft was fitted with a small fixed tailwheel assembly to keep the proptips from scraping the runway on take-off. There was no tailfin. The Jeep originally had downturned wingtips, but it was later modified with straight wingtips,

The aircraft, in maturity, featured a wingtip control assembly variously known as a "rudderon", "deceleron", or "split flap drag rudder". It was a control surface on the rear of the wing near the wingtip that could be deflected up, down, or split top and bottom to be deflected both ways. When one was opened up, it caused the aircraft to turn; when they were both opened up, they acted as airbrakes. The Jeep still had "elevon" control surfaces inboard of the rudderons to provide climb and dive (elevator) or roll (aileron) control.

The N-1M had a length of 5.46 meters (17 feet 11 inches) and a span of 11.8 meters (38 feet 9 inches), with a weight of about 1,800 kilograms (4,000 pounds). It was painted bright chrome yellow. It proved underpowered, and so the Lycoming engines were replaced by Franklin 0-300 flat-six air-cooled engines with 87 kw (117 HP) each, driving three-bladed propellers. It helped give Jack Northrop a handle on how to build a more practical flying wing. The N-1M still survives, on display at the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum in Washington DC.

* By the end of 1941, America was at war and Northrop was building more conventional aircraft to support the war effort. The most significant contribution of the company to the war effort was the big twin-engine P-61 Black Widow night fighter, a capable machine though it arrived too late in the conflict to have a significant influence on the course of events.

Northrop hadn't given up on the flying wing. Even before America entered the war, the military had given thought to a bomber that could fly across the Atlantic, drop its bombload, and fly back again. If Britain fell to the Nazis, such a weapon would be a necessity. The slogan was simple: "10,000 pounds of bombs for 10,000 miles" -- 4,500 kilograms for 16,000 kilometers.

Contracts were let to Consolidated Aircraft for the huge "B-36", which would be of more or less conventional configuration and be powered by six huge piston engines buried in the wings, driving pusher propellers. Northrop also got a contract for the "B-35", which would be a flying wing powered by four large piston engines driving pusher propellers. Ultimately, Northrop would receive orders for two "XB-35" prototypes, 13 "YB-35" evaluation machines, and 200 production B-35 bombers.

Northrop built four more small experimental flying wings under the designation of "N-9M" to validate design concepts for the XB-35. The N-9Ms had a general similarity to the N-1M -- all-wing configuration; twin pusher engines; retractable landing gear, adding a long-arm retractable tailwheel to protect against ground strikes -- but were much bigger, more refined, and more elegant. Each was given a slightly different designation, in the sequence:

They had a tandem canopy for a pilot and an observer. The first two were painted all yellow; the third was blue on top and yellow underneath; the fourth was yellow on top and blue underneath. The first three were powered by Menasco C6S-4 Super Buccaneer six-cylinder air-cooled inverted inline engines with 205 kW (275 HP) each while the fourth, the N-9MB, was powered by Franklin flat-eight air-cooled X/O-540-7 engines with 225 kW (300 HP) each. In all cases, they drove two-bladed Hamilton Standard variable-pitch propellers.

___________________________________________________________________

NORTHROP N-9M:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

18.3 meters (60 feet)

wing area:

45.6 sq_meters (490 sq_feet)

length:

5.41 meters (17 feet 9 inches)

height:

2.0 meters (6 feet 7 inches)

normal loaded weight:

2,828 kilograms (6,326 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

415 KPH (258 MPH / 224 KT)

service ceiling:

5,945 meters (19,500 feet)

range:

800 kilometers (500 MI / 435 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

There were minor variations between each N-9M -- for example, the N-9MA had a prominent fixed slot near the outer leading edge of the wing not present in the previous two N-9Ms, with the N-9MB featuring a closeable slot instead. The slot set up turbulence that prevented "airflow separation" from the top of the wing at low speeds and high angles of attack, delaying the onset of a stall. Initial flight of the first N-9M was on 27 December 1942, with test pilot John Myers at the controls. Unfortunately, this machine was lost in March 1943 during stall testing, pilot Max Constant being killed.

Modifications were made to the N-9Ms in the course of their flight trials. The N-9MB ended up in the hands of the Chino Planes of Fame air museum in the Los Angeles, California, area, and in fact was restored to flight status. It was lost in a fatal crash in 2019.

BACK_TO_TOP* While Northrop's main focus was on building the XB-35 bomber, the company also went off on other design paths, including a flying-wing fighter. The original concept was for a rocket-propelled fighter designated the "XP-79" in which the pilot flew in a prone position -- partly for streamlining, partly to handle gee forces, through proper neck support was a difficulty. The XP-79s were to be powered by a liquid-fuel Aerojet rocket engine providing 8.9 kN (905 kgp / 2,000 lbf) thrust, with take-off assisted by twin solid-fuel "jet assisted take-off (JATO)" boosters providing 4.45 kN (450 kgp / 1,000 lbf) thrust each.

Three prototypes were ordered in January 1943, with the concept originally evaluated by unpowered gliders, built of wood with fixed tricycle landing gear -- the nose gear in a spat, the main wheels in underwing fairings -- and a wingspan of 9.75 meters (32 feet). They were given the designation of "MX-334". Although Jack Northrop never liked the idea of cluttering up his clean flying wings with a tailfin, calculations and wind-tunnel work showed there was no way around fitting one. Three were built, being towed into the air by Lockheed P-38 fighters. One was lost when it got caught in the P-38's propwash and stalled, pilot Harry Crosby bailing out successfully.

One was actually fitted with a prototype Aerojet rocket motor and flew as the "MX-324", but engine development proved troublesome and there may have been misgivings about using rocket propulsion anyway -- pure rocket fighters had blazing performance but pathetic endurance and excessive fire hazard, and would prove to be a very bad idea. The decision was made to not build two of the rocket-powered XP-79 prototypes; the third was to be built with twin Westinghouse J30 (19-B) turbojets.

The result was the "XP-79B", definitely one of the most unusual aircraft flown during World War II. It retained the prone pilot position of the gliders, but added retractable landing gear, in a "quadracycle" configuration, four wheels in a "baby buggy" configuration; twin tailfins; and a Westinghouse J30 engine in a nacelle on each side of the cockpit, with each engine providing 6.1 kN (620 kgp / 1,365 lbf) thrust. Wingspan was 11.6 meters (38 feet) and take-off weight was 3,930 kilograms (8,670 pounds).

The XP-79B had a puzzling little inlet on each wingtip, which provided ram air to a bellows to help actuate the rudderons. The pilot flew the aircraft with a crossbar handle and foot pedals. Armament was to be four 12.7-millimeter (0.50-caliber) Browning M2 machine guns in the wing leading edge, though it wasn't fitted in the prototype.

One of the particularly odd features of the XP-79B was the notion that it would be used in ramming attacks on enemy aircraft. The original specification never mentioned the idea, and it was preposterous on the face of it -- trying to execute a ramming attack without damaging the canopy, tailfins, and engines might be very tricky, and there was no sense in getting any closer than needed to a target's defensive armament anyway. Even training to perform such attacks would be problematic, and no pilot would have resorted to ramming as anything but an act of desperation.

However, Jack Northrop himself stated: "It was designed as a projectile, with the thought that it could be used to intercept and knock wings or tails off other airplanes." Where this dubious notion came from is unclear -- the aircraft was built strong and possibly some engineer, maybe Northrop himself, suggested it could be used in ramming attacks, and threw it out as marketing hype. If the concept was taken seriously at Northrop, it seems unlikely that USAAF brass thought much of it.

The XP-79B was hauled out to Muroc Dry Lake (now Edwards Air Force Base) in June 1945, to perform its first flight on 12 September 1945, with Harry Crosby at the controls. It was also its last: the aircraft flew fine for about 15 minutes, then went into an unrecoverable spin. Crosby managed to get out, but his parachute didn't open fully and he was killed. Although the cause of the accident was determined and was fixable, by that time the USAAF had lost interest in the program and that was the end of it.

While it seems unlikely that the XP-79B would have ever gone to production, even disregarding the tragic death of Harry Crosby it was a pity it didn't go through full trials. Practical or not, no aircraft looked more like a 1940s science-fiction prop, and video footage of the thing flying around would be fascinating.

Northrop also worked on a series of flying-wing cruise missiles, the "JB-1" and "JB-10", using a manned glider (with upright seating this time) as a demonstrator, once again towed into the air by a P-38. This topic is discussed in more detail in a companion document on cruise missiles.

BACK_TO_TOP* Along with the XP-79, Northrop also developed two "tailless" aircraft -- with a fuselage, wings, a tailfin, but no tailplane. The first began with Army Air Corps "Request for Proposal R-40C", issued in 1940, specifying a fast, high-altitude, long-range interceptor, with vendors encouraged to "think out of the box". Northrop engineers had already been thinking out of the box, and returned a proposal for a tailless fighter with a pusher engine; the Air Corps like the proposal, and funded a flight prototype. A second prototype would follow later.

The XP-56 had a short, blunt fuselage, with a pusher prop driven by a Pratt & Whitney R-2800 28-cylinder two-row air-cooled engine providing 1,500 kW (2,000 HP). The prop was contra-rotating, with three variable-pitch blades on each prop stage; the engine intakes were in the wing roots. It was supposed to be powered by the P&W X-1800 24-cylinder H-block liquid-cooled inline engine, but it didn't materialize; using the radial engine meant a bigger fuselage. The aircraft was 8.38 meters (27 feet 6 inches) long, had a wingspan of 12.96 meters (42 feet 6 inches), and an empty weight of 3,955 kilograms (8,700 pounds).

The XP-56 had inverted gull wings, a dorsal tailfin -- in part to keep the prop off the runway -- and a small ventral tailfin. It had the wingtip inlets like the XP-79; they were actually developed for the XP-56. It featured retractable tricycle landing gear, all gear assemblies with single wheels, main gear tucking in from the wings towards the fuselage, nose gear retracting backward. The XP-56 was built of magnesium alloy, apparently out of fear of aluminum shortages. It was to be armed with twin 20-millimeter cannon and four 12.7-millimeter (0.50-caliber) Browning M2 machine guns, but it is not clear if the prototypes were ever fitted with armament.

Initial flight of the first prototype, tailcode 41-786, was on 30 September 1943, with the aircraft demonstrating bad yaw instability; the ventral tailfin was enlarged to about the same size as the dorsal tailfin, solving this problem. The first prototype was damaged beyond repair on 8 October 1943 when a tire blew out during a high-speed taxi run; the pilot, John Myers, survived without serious injury.

The second prototype, tailcode 42-38353, flew on 23 March 1944. It featured some changes in ballasting, a larger ventral tailfin, and modified rudder control. It could not reach design speed and handling was difficult; it only performed ten flights before the decision was made that the XP-56 was unsafe to fly, with the program abandoned a year later. The second prototype ended up in the hands of NASM, but hadn't been restored at last notice.

* Although the XP-56 was a dead end, the USAAF awarded a contract to Northrop in 1946 to build two prototypes of a tailless jet research aircraft, with the first "X-4 Bantam" flying on 15 December 1948 from Muroc Air Force Base in California -- Charles Tucker at the controls. It was a small aircraft of all-metal construction with a stubby fuselage, swept wings, a tailfin, and retractable tricycle landing gear -- all gear with single wheels, the main gear retracting from the wings towards the fuselage, the nose gear retracting backwards.

The X-4 was powered by twin Westinghouse J30-WE-7 / WE-9 turbojets with 7.1 kN (725 kgp / 1600 lbf) thrust each. It had split flaps that also worked as air brakes. The bubble canopy hinged up from the rear. Length was 7.09 meters (23 feet 3 inches), wingspan was 8.18 meters (26 feet 10 inches), and empty weight was 2,500 kilograms (5,510 pounds).

The idea behind the X-4 was that the wing and the tailplane did not play well together at transonic speeds, leading to flight instability, and so it seemed to make sense to get rid of the tailplane. The first prototype turned out to be unreliable, and only flew ten times before it was grounded, to be scavenged for the second prototype. It was flown from 1950 to 1953 by the High-Speed Flight Research Station of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), the principal ancestor of the modern National Aeronautics & Space Administration (NASA).

Early flight tests demonstrated that the X-4 was unstable around all three flight axes and tended to "washboard", oscillating violently, at transonic speeds. Well-known test pilot Scott Crossfield called it "capricious and delicate to handle", saying that at transonic speeds it sounded like a "freight train crossing a steel bridge."

The conclusion of the test program was that the X-4's configuration was unsuitable for high-speed flight. The tailless delta wing configuration, however, was very much suited to supersonic flight, with research in the era leading to the Convair F-106 Delta Dart interceptor and B-58 Hustler bomber. Both X-4 prototypes survived and are now museum displays.

BACK_TO_TOP* Work on the XB-35 flying-wing bomber continued through World War II, if at a slow pace. The payload-range requirement in the original USAAF request was unreasonable -- it would be hard to do even today -- and as the war turned against the Axis, the need for a trans-Atlantic bomber faded. However, the project didn't die out.

The first XB-35 prototype performed its initial flight on 25 June 1946. The first rival "XB-36" followed in August, and appeared less promising. It did not appear capable of meeting its design goals, and Convair -- as Consolidated had become after merging with Vultee during the war -- found getting the aircraft on track difficult.

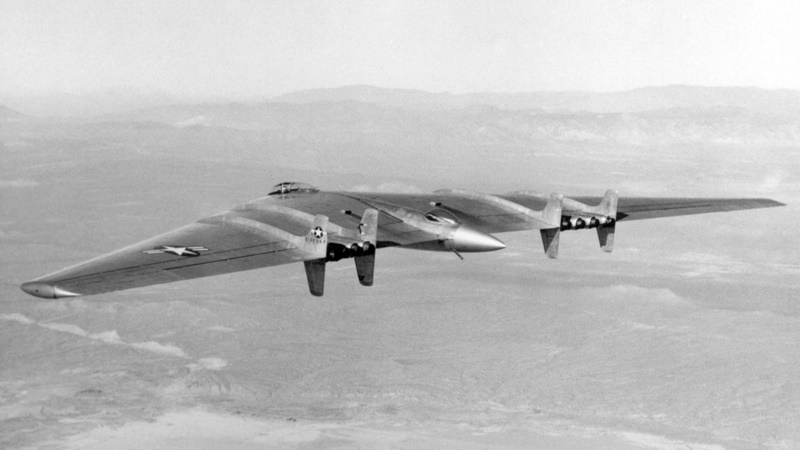

The second XB-35 prototype performed its initial flight on 26 June 1947. As the XB-35 emerged, it was a huge flying wing, built mostly of aircraft aluminum and driven by four Pratt & Whitney (P&W) R-4360 air-cooled, four-row, 28-cylinder radial engines, each driving a pusher propeller through a driveshaft and providing a maximum of 2,240 kW (3,000 HP). The Hamilton-Standard propellers were of contra-rotating configuration, with each stage featuring four blades. There were wide slot engine intakes in the leading edge of the wing.

The wing featured rudderons at the tips, a flap on each wing between the engines, a wider "elevon" control surface outboard of the engines, and a slot in the outer front top of the wing that closed or opened automatically. Controls were actuated using a dual-hydraulic system; an "artificial feel" system monitored the elevons to give the pilot feedback. There were no tailfins. Landing gear was of tricycle configuration, all electrically actuated, with twin-wheel main gear in the wing between the inboard and outboard engines retracting forward, and single-wheel nose gear retracting sideways to the left.

Normal crew was nine, including a pilot, copilot, bombardier, navigator, engineer, radio operator, and three gunners. There were folding bunks to the rear for six relief crew for long missions. The pilot sat in a bubble canopy offset to the left of the aircraft's centerline, with the copilot sitting within the wing to the right, seeing out through glazing in the wing leading edge. The bombardier sat to the right of the copilot, aiming through a glazing beneath the wing. Radio operator, flight engineer, and navigator were in a compartment to the rear, with an astrodome on top for the navigator to take sextant readings.

Defensive armament consisted of 20 guns in seven remote-control positions -- a two-gun turret above and below each wing, a four-gun turret above and below the center section, and a four-gun tail stinger. The guns were all Browning M2 machine guns, though apparently there was consideration of using 20-millimeter cannon in production. There were crew sighting bubbles on the rear fuselage for the guns, though neither XB-35 was ever armed. There were four separate bomb bays in each wing -- three inboard of the main gear well and one outboard -- with a maximum total bombload of 23,675 kilograms (52,200 pounds).

___________________________________________________________________

NORTHROP XB-35:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

52.4 meters (172 feet)

wing area:

371.8 sq_meters (4,000 sq_feet)

length:

16.18 meters (53 feet 1 inch)

height:

6.1 meters (20 feet)

normal loaded weight:

73,470 kilograms (162,000 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

630 KPH (390 MPH / 340 KT)

service ceiling:

12,195 meters (40,000 feet)

range:

12,075 kilometers (7,500 MI / 6,520 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

The two XB-35s were built, but they proved unsatisfactory. The contraprops and the drive system were very unreliable, leading to their grounding by September 1947. They were refitted with ordinary four-bladed propellers and returned to the air in early 1948. The new props helped a lot with the mechanical problems -- but the props couldn't provide adequate power transfer, and performance suffered. Only one YB-35 was completed, performing its initial flight on 15 May 1948. Unlike the XB-35s, it was fitted with defensive armament.

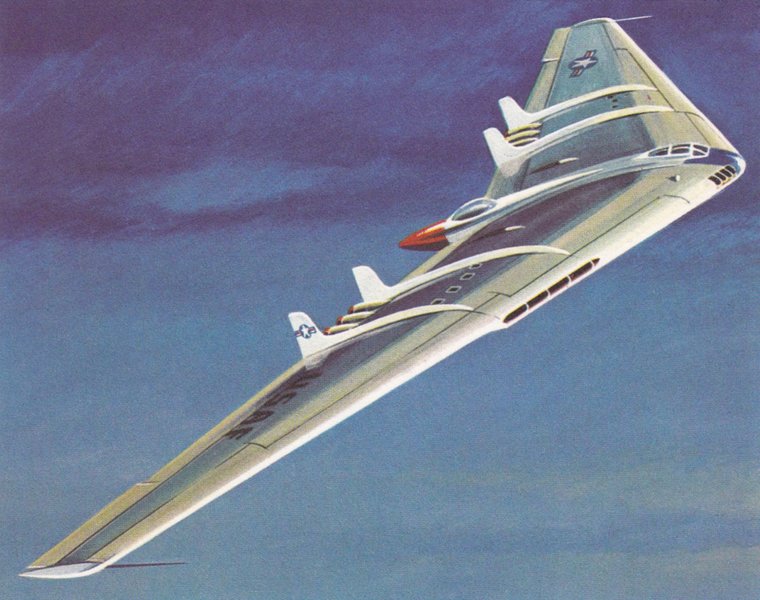

BACK_TO_TOP* Along with two XB-35s and the single YB-35, 12 more B-35-type flying wings were planned, though none would fly as B-35s. The USAAF was losing interest in piston bombers, jet aircraft being clearly seen as the way of the future. In late 1944, Northrop had proposed a jet derivative of the B-35, to be designated the "B-49". Two of the planned flying wings were accordingly built as "YB-49" prototypes -- originally to be designated "YB-35B" -- the first performing its initial flight on 24 October 1947. It was followed by a second YB-49, which performed its initial flight on 13 January 1948.

The general dimensions of the YB-49 were of course identical to those of the XB-35. It was powered by eight Allison J-35A turbojet engines, with the engines arranged in parallel quads in each wing and intakes in a slot in the front of the wing. Yaw stability was more of a problem with the YB-49 than it was for the XB-35, and so the jet flying wing had four tailfins, protruding above and below the wing, with a tailfin inboard and outboard of each engine array, and a long "fence" in front of each tailfin on the top of the wing. All the defensive armament except the tail stinger was deleted. The fuel-hungry jet engines cut range, and warload was reduced to 14,510 kilograms (32,000 pounds).

___________________________________________________________________

NORTHROP XB-49:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

52.4 meters (172 feet)

wing area:

371.8 sq_meters (4,000 sq_feet)

length:

16.18 meters (53 feet 1 inch)

height:

4.63 meters (15 feet 2 inches)

normal loaded weight:

87,955 kilograms (193,940 pounds)

max speed at altitude:

795 KPH (495 MPH / 430 KT)

service ceiling:

12,410 meters (40,700 feet)

range:

5,080 kilometers (3,155 MI / 2,745 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

Some sources claim that pilots found the YB-49 elegant to fly -- though other sources point to its instability, it being too much like a boomerang to fly very straight. The public found the flying wing design fascinating and popular science magazines played it up as the "aircraft of the future". Unfortunately, the second YB-49 was lost in a crash on 5 June 1948, all the crew being killed. It turned out the aircraft had suffered a structural failure in a dive test. Muroc AFB was subsequently renamed "Edwards AFB" after the late pilot, Captain Glenn Edwards.

* Despite the accident, the flying wing did seem to have a very promising future. Late in June 1948, Jack Northrop was visited by US Air Force General Joseph McNarney, a big cheese in the USAF procurement hierarchy, and gave him an order for 30 "RB-49A" reconnaissance machines. McNarney assured Northrop that large numbers of orders would follow. A single "YRB-49A" machine was built, differing from the YB-49s in having no tail stinger, and reducing the number of engines to six -- with four in the wing itself and two mounted under the wing on pylons. Jack Northrop hated tacking on the engines under the wing, but it freed up space in the wing for fuel tanks, particularly by trimming back on the complicated wing ducting. It performed its initial flight on 4 May 1950.

By that time, the program had run into fatal turbulence. Since Northrop didn't have production facilities adequate to build the RB-49A in quantity, it was to be built in the Convair plant in Fort Worth, Texas, which was owned by the government. It might have been satisfying for Northrop to realize that his rival, Convair, would not only lose the contest but would have to support flying wing production, but that blade cut both ways. Coming to an agreement with Convair on production proved troublesome; and then on 16 July 1948, Secretary of the Air Force Stuart Symington bluntly told Northrop that his company had to merge with Convair.

The two companies couldn't agree on a merger either, and then things began to go from bad to worse for Jack Northrop. The B-36 was finally demonstrating most of the range and payload for which it had been designed. The flying wing, in contrast, was still not meeting its range specifications, and its thick wing ensured that its performance would always be limited. The Air Force had only turned to the flying wing when the B-36 program appeared to be close to collapse; when it revived, the B-49 didn't have a chance.

In early 1949, Symington ordered increased production of the B-36. Since money was tight, that meant killing other projects. On 11 January 1949, the flying wing was canceled. There was something of a scandal over the decision, with critics charging that Symington's actions were part of a plot to build an aviation super-company that he would eventually lead. There were hearings over the matter in August 1949. There was no evidence to support any of the charges and the issue was dismissed, permanently.

Jack Northrop continued to insist that Symington had been up to no good, cancelling the RB-49A when Northrop didn't go through with the merger with Convair. There was no evidence to support this accusation, and in fact in March 1949 the Air Force had given Northrop a big contract to build the F-89 Scorpion all-weather interceptor. With the Cold War slowly brewing up, Symington needed to improve America's strategic defense posture as quickly as possible, and if that meant stepping on the toes of people like Jack Northrop, that was just too bad. In any case, the Air Force was already acquiring much faster bombers like the Boeing B-47, capable of speeds that the B-49 could never touch.

Nine unfinished flying wings -- most of which were to be completed to RB-49A spec, with a few to be used for trials -- were scrapped, as were the survivors of the six that flew. Tragically, none of them ended up in an air museum. The whole fiasco took the wind out of Northrop. In November 1949, all 11 of the flying wing bombers that had been built were scrapped -- except for the first YB-49, which had been destroyed in a fire after a ground accident on 15 March 1950. Tragically, none of the flying wing bombers went to air museums. He divorced his wife, and in 1952 he resigned from the company even though he was only 57 and business was good.

* Jack Northrop would, in the end, receive some vindication. In April 1980, after he had been left mute by a stroke, he was driven to a secret office at Northrop and shown plans for a new aircraft in the works: the B-2 stealth flying wing bomber, to be built by Northrop. He died some months later and never got to see it fly, but it was a satisfaction to know that his work hadn't been forgotten after all.

BACK_TO_TOP* The flying wing configuration was very attractive to aircraft designers in the 1940s. It seemed to promise a highly efficient aircraft, since the form of the aircraft included little that did not provide lift.

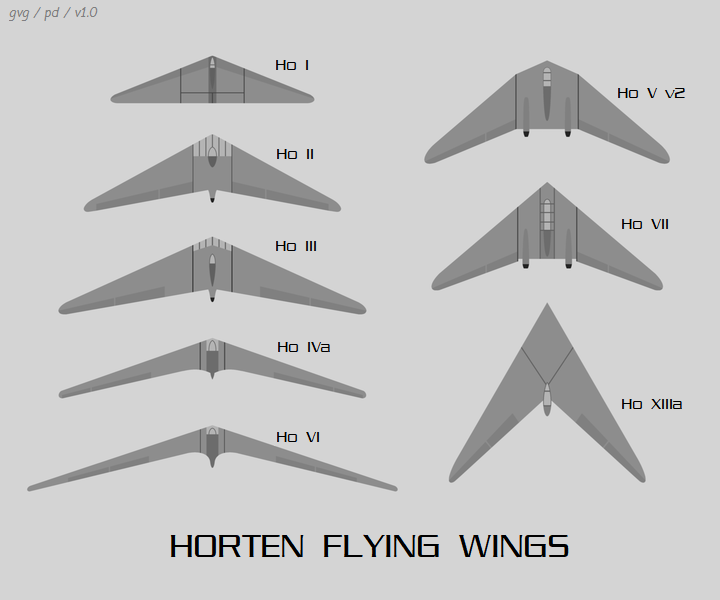

Jack Northrop's German counterparts were the Horten brothers, Reimar and Walter. They developed a series of gliders and powered aircraft to test their flying wing concepts, including:

From 1936, the Hortens were both Luftwaffe officers, in which capacity they continued their interest in flying wings. In 1942, they came up with a concept for a flying-wing jet fighter. They began by building a trainer, the "Ho VII", which had dual controls and two 180 kW (240 HP) Argus air-cooled inverted-vee As-10 piston engines, driving pusher propellers. Two were built. Since the Hortens were performing this development on their own initiative and without RLM approval, they formally described the Ho VII as a "research aircraft", which had enough truth in it to be not quite a complete lie. Incidentally, the Hortens also worked on an "Ho VIII", with ambiguous descriptions in the literature, but in any case it wasn't flown.

The actual fighter design was designated the "Ho IX". The Hortens had shown drawings of their flying-wing fighter to Reichsmarshall Hermann Goering, and they had his personal backing for the project. The first prototype of the Ho-IX, the Ho IX V1, was originally built as an unpowered glider, first flying in 1 March 1944. By May, the potential of the Ho IX was apparent, and the RLM had authorized development, ordering more prototypes and 20 production aircraft. Manufacturing was assigned to the Gotha company, and the production fighter was to be designated the "Gotha Go 229".

Some sources claim the Ho IX V1 was later fitted with twin BMW 003 engines, but in any case it was lost in a crash later in 1944. Work on the second prototype, the powered Ho IX V2, was delayed because the required Junkers Jumo 004B engines were not available, and the Ho IX V2 did not fly until just before Christmas, 1944. It only logged two hours of flight time before it crashed on 18 February 1945.

Work on the Ho IX V3, which was closer to production spec, moved slowly due to economic dislocations caused by Germany's military collapse. While the engines of the Ho IX V2 were smoothly buried in the wings, the engines on the Ho-IX-V3 protruded up through fairings on top of the wing.

The Ho IX V3 was almost complete when US forces occupied the factory, and was shipped to the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum, where it resides today. The V4 and V5 prototypes were intended for development of a two-seat night-fighter variant that was not built. The V6 prototype was the production prototype for the Go 229 day fighter variant, with much external resemblance to the V3, but considerable re-engineering under the skin.

The Go 229 was a pure flying wings. The center section was framed with steel tubing, the wings were of wooden construction, and the entire aircraft was skinned in plywood. Some components were made out of a wood composite named "Formholz", which was something like particle board molded to specific shapes under pressure. The Go 229 featured tricycle landing gear, and the cockpit was fitted with a crude ejection seat. It was to be armed with four MK 103 or MK 108 30-millimeter cannon and would be able to carry two 1,000-kilogram (2,200-pound) bombs.

The Go 229 was to have a wingspan of 16.8 meters (55 feet), a length of 7.47 meters (24 feet 6 inches), an empty weight of 4,600 kilograms (10,140 pounds) and a fully loaded weight of 8,100 kilograms (17,860 pounds). Performance was estimated at 970 KPH (600 MPH) at 11,900 meters (39,000 feet). Range was expected to be a remarkable 1,900 kilometers (1,180 miles) without drop tanks, or 3,170 kilometers (1,970 miles) with drop tanks.

* The Hortens considered a supersonic delta rocket-jet fighter, the "Ho X", but only got as far as building a pusher-prop demonstrator that was never completed. They did fly a single demonstrator glider, the "Ho XIII", to evaluate a highly-swept flying wing configuration, with a pilot's gondola tacked on under the rear of the wing.

In addition, they drew up designs for a huge bomber flying wing, the "Ho XVIII", with enough range to fly to America, hit New York or Washington with 4 tonnes (4.4 tons) of bombs, and return to Germany. The RLM issued a requirement for an "Amerika Bomber" in 1944, with five companies providing designs, none of which were acceptable. The Hortens weren't invited to submit a design, the perception being that they were focused on fighters, but when they learned about the Amerika Bomber competition very late in 1944, they came up with a proposal for a big flying wing designated "Ho XVIIIA", made mostly of nonstrategic materials and powered by various engine arrangements, such as eight Jumo 004B turbojets buried in the center of the wing.

The flying wing configuration promised aerodynamic efficiency and lots of space for fuel tanks, making it possible for a jet-powered aircraft to meet the range requirement in an era when jet engines were notorious fuel hogs. The Hortens pitched their design to the RLM in February 1945 and RLM officials were very interested -- but they then handed the design over to a committee of aircraft designers from other firms, who added such things as a tailfin and moved the engines beneath the wing.

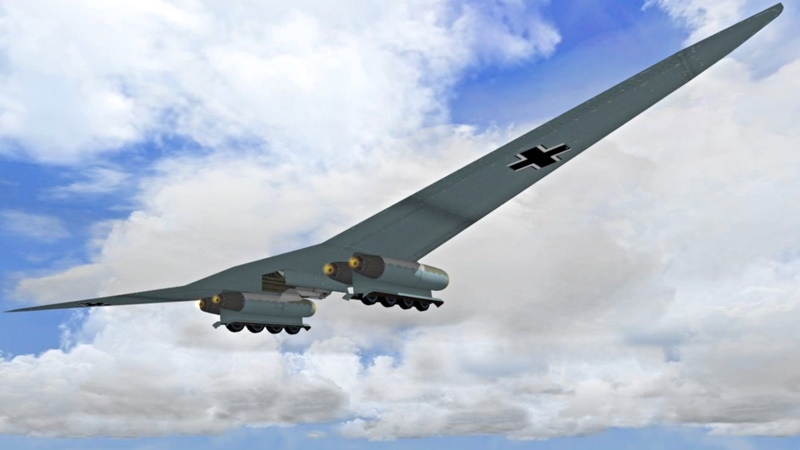

The Hortens were appalled since such changes reduced the aerodynamic efficiency of the aircraft, and came up with their own "Ho XVIIIB" design that swallowed some of the concerns of the RLM to give a solution more on the Horten's own terms. The Ho XVIIIB was to be a flying wing with fixed landing gear in the form of a pylon-like fairing under each wing that featured four wheels in series; the wheels were covered by aerodynamic doors in flight. A single Heinkel-Hirth HeS 011 turbojet was fitted on each side of both landing gear fairings, giving a total of four engines.

The three crew sat under a single bubble canopy in a pressurized cockpit. There was to be no defensive armament, the aircraft obtaining protection from speed and altitude -- even if a fighter could reach its altitude, the flying wing, with its huge wing area, would be easily able to outmaneuver it. The Hortens did provide variant designs with defensive armament in case the RLM insisted.

As envisioned, the Ho XVIIIB was to have a loaded weight of about 35 tonnes (38.5 tons), a span of 40 meters (131 feet 4 inches), a top speed of 850 KPH (528 MPH), a ceiling of 16,000 meters (52,500 feet), and a range of 11,000 kilometers (6,835 miles). It was an impressive idea, but like many of Germany's last-gasp weapons, was nothing more than a paper fantasy. Other German aircraft manufacturers considered flying-wing designs, but none of them ever came to anything, either.

* Reimar Horten emigrated to Argentina after the war, where he continued to design gliders and powered aircraft. He died there in 1994. Walter stayed in Germany, becoming an officer in the revived Luftwaffe, and died there in 1998. The Hortens have acquired something of a legendary status, as visionaries far ahead of their time -- with many comments about the "stealthiness" of their designs, just as with Jack Northrop. In reality, while they were ingenious, in practice they were tinkerers, who made no major contributions to aircraft design.

BACK_TO_TOP* Neither the Northrop nor Horten flying wings amounted to much, but the flying wing is alive and well in the 21st -- most spectacularly in the form of the B-2 Stealth bomber and its follow-on B-21 Raider bomber. It is also common among drones, and efforts are currently under way to develop "blended-wing body" aircraft that are clearly evolved from flying wings. Flying wings have become more practical because of improved aerodynamic knowledge, advanced airframe materials, and in particular very smart fly-by-wire control systems. However, modern flying wings are another story.

* Sources include:

* Illustration credits:

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 mar 23 / gvgBACK_TO_TOP