* The Grumman F4F Wildcat was a stubby, tough little carrier-based naval fighter that not only helped save the day for the US Navy in the difficult early days of World War II, but gave outstanding service through the rest of the war with the navies of both America and Britain. This document gives a history and description of the Wildcat.

* Near the end of 1935, the US Navy issued a request for a new high-performance carrier-based fighter. The Grumman company, which was working on the biplane F3F "Flying Barrel" fighter at the time, responded with the "Model G-16" -- another biplane design, but with a more powerful engine -- either a Wright XR-1670 radial with 595 kW (800 HP) or a P&W XR-1535 radial with 650 kW (875 HP). Top speed of the G-16 was projected as being about 425 KPH (265 MPH).

The Navy issued Grumman a contract for a prototype, to be designated the "XF4F-1". However, while the company was trying to get the prototype out the door, the USN ordered a prototype of a competing design, the "XF2A-1", from the Brewster Company. The Brewster offering was a monoplane and was seen as more modern in configuration. Grumman's chief designers, Dick Hutton and Bill Schwendler, saw the light and quickly converted their biplane design to a mid-wing monoplane configuration, with the Navy agreeing to the change in July 1936. The new design was designated the "Model G-18" and was given the Navy designation "XF4F-2".

The XF4F-2 performed its initial flight on 2 September 1937, with company test pilot Robert L. Hall at the controls. The XF4F-2 was a mid-wing monoplane with non-folding wings; a P&W R-1830-66 air-cooled 14-cylinder two-row Twin Wasp radial engine with 785 kW (1,050 HP) driving a Hamilton Standard three-bladed variable-pitch prop; and retractable landing gear in a taildragger configuration, with the main gear tucking into the fuselage and a fixed, swiveling tailwheel. Armament consisted of twin 7.62-millimeter (0.30-caliber) Browning machine guns mounted in the top of the engine cowling and firing through the propeller arc, and a 12.7-millimeter (0.50-caliber) Browning in each wing, for a total of four guns.

* Full naval trials pitting the Grumman and Brewster designs against each other took place at NAS Anacostia, in the Washington DC area, in early 1938. The Grumman offering suffered from engine overheating, and in fact an engine failure on 11 April 1938 led to a rough landing in a farm field that flipped the aircraft over onto its back. The pilot, a Navy lieutenant named Gurney, was not seriously hurt, but the machine was badly damaged and had to be sent back to the factory for repairs.

Due to engine and other problems with the XF4F-2, the competing Brewster design was selected for production in June 1938 under the name "Buffalo". The Buffalo was the Navy's first fully operational monoplane fighter, though it would have a generally infamous combat career later. Fortunately, there were those in the Navy procurement bureaucracy who were skeptical of the Buffalo's potential, and so Grumman was awarded a contract in October 1938 to rebuild their prototype into an improved configuration, the "Model G-36" or "XF4F-3".

The XF4F-3 first flew on 12 February 1939, once again with Bob Hall at the controls. It featured an XR-1830-76 Twin Wasp engine with 895 kW (1,200 HP) and a two-stage supercharger; fuselage modifications; a bigger wing, with square instead of rounded wingtips; and a modified tailfin. Additional modifications were added after evaluation flights, such as a further redesigned tailfin with a forward extension and the tailplane moved up onto the tailfin. Experiments were performed with an oversized prop spinner to improve aerodynamics, that being something of a "fad" in aircraft design at the time -- but as was the case with most of these exercises, the spinners turned out to be little more than dead weight and were abandoned.

Performance was excellent, the Navy was impressed, and Grumman was awarded a production contract for 78 "F4F-3s" in August 1939, with the first production aircraft flying in February 1940, followed by formal Navy acceptance in January 1941. The type would be officially given the name "Wildcat" in the fall of 1941, before Pearl Harbor. It is unclear if this name was in unofficial use before that time, but for simplicity the name "Wildcat" is used throughout this document.

BACK_TO_TOP* As the F4F-3 emerged, it was a stubby, barrel-like aircraft, with mid-mounted square-tipped wings and a sliding frame-style canopy. There was also a small window on each side of the floor of the cockpit to give a pilot better downward visibility -- though in practice, the belly windows proved nearly useless. Cockpit armor was added after the first few production aircraft. An inflatable life raft was carried in the fuselage behind the cockpit and could be ejected on ditching, but it was later deleted in favor of a raft in the pilot's survival pack. Inflatable flotation bags were fitted under the wings for ditching at sea, but after the bags spontaneously inflated in flight a few times, leading to crashes, they were abandoned. Electronics included a radio and, at least eventually, a radio direction finder and an identification friend or foe (IFF) unit.

Two 12.7-millimeter Browning machine guns were mounted on each wing, for a total of four guns. The guns were mounted inboard, close together on each wing, with the inner gun staggered forward slightly. Ammunition capacity was 450 rounds per gun. The first two production machines had twin 7.62-millimeter Brownings in the engine cowling and a single 12.7-millimeter M2 Browning in each wing as per the prototypes, but that armament was seen as too light, and no full production Wildcat had cowling guns. The Browning guns would prove prone to jamming when the Wildcat finally found itself in combat, even though such problems hadn't been observed during trials. As it turned out, the trials hadn't been conducted with full ammunition loads, and when a full supply of ammunition was provided the ammo belts would shift around in their ammo cases during combat maneuvers, leading to jams. Spacers were quickly fabricated and inserted into the ammo cases, solving the problem.

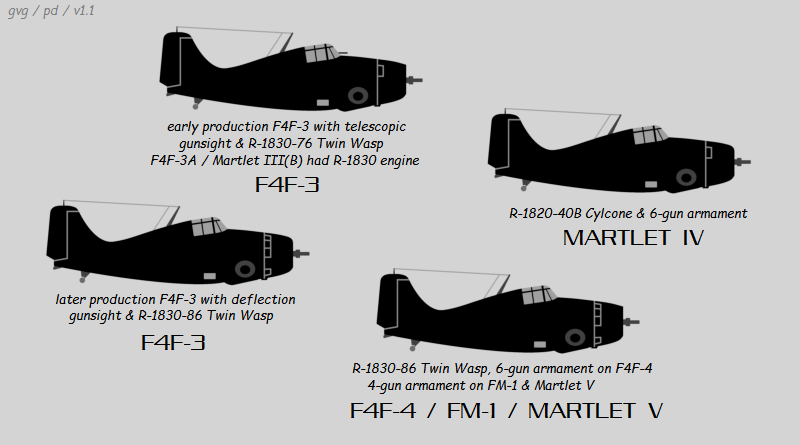

Early production aircraft had a 1930s telescopic-style gunsight, but in 1941 production shifted to a deflection-type sight. An armor glass windscreen and self-sealing fuel tanks were also added later. The self-sealing tanks led to some problems early on, since they could shed particles of their lining, leading to clogged fuel lines and aircraft losses. There was a stores rack under each outer wing for a 45-kilogram (100-pound) bomb.

Early production aircraft also used a P&W R-1830-76 Twin Wasp with a two-stage supercharger, while later production used the R-1830-86 Twin Wasp, which was much the same but had some modifications to improve reliability. Fit of the later engine variant was accompanied by a modified cowling, which eliminated an air scoop in the upper lip, and replaced one wide cowling flap on the upper rear of each side of the cowling with a set of three flaps near the top and a single flap near the bottom -- in sum, replacing two flaps with eight. The Twin Wasp engine drove a three-blade variable-pitch Curtiss Electric propeller. Engine cooling problems during evaluation led to the fit of "cuffs" at the base of the propeller blades to increase airflow to the engine, with production aircraft retaining the cuffs.

The square-tipped wings were fixed and could not be folded. The flight surface arrangement was conventional, with ailerons outboard on each wing, a one-piece wide-span flap under each inner wing, and a tail assembly with elevators and rudder. The main landing gear retracted into the fuselage, and a stinger-type arresting hook extended backward from the tail. The landing gear was manually retracted, with the pilot turning a crank 29 times to tuck the gear into the fuselage. As a result, Wildcats tended to wobble on take-off, since it was hard for a pilot to keep a steady grip on the stick with one hand while spinning the crank with the other.

Pilots were not enthusiastic about the manual landing gear. It was not only laborious -- but if a pilot's hand slipped off the crank it would spin around wildly, possibly injuring the pilot's wrist in the process. The narrow "roller skate" track of the main landing gear was also a problem. It generally didn't cause too much trouble on carrier landings since the arresting cable caught the aircraft before it could wander far, but ground looping was common when landing on airstrips. Pilots were also not happy with the cramped cockpit, which provided poor visibility, and were very unhappy at the lack of a simple mechanism for discarding the canopy so they could get out in a hurry when things got difficult.

However, the F4F-3 had good performance, by the standards of the time, and was built very rugged, establishing Grumman's reputation with pilots as the "Iron Works". The Grumman motto was: "Make it strong, make it work, make it simple." Engineers were encouraged to overdesign the machines, ensuring they exceeded Navy requirements by what was called a "Schwendler factor". The USN liked the F4F-3, ultimately buying a total of 285.

* The subject of Wildcat variants is confusing, since most Wildcat models looked much alike, and the changes followed an irregular pattern. Even before the Wildcat had reached formal US Navy service, both the French Navy and the British Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm (FAA) had ordered the Wildcat, specifying their own unique configurations:

That was the plan, but wasn't exactly how things turned out. Trials of the French G-36A began on 11 May 1940, but France fell to the Nazis that month and the French never saw these machines. The British took over the order and the machines were delivered to the FAA beginning in late July 1940 under the designation of "Martlet Mark I" -- a "martlet" being a legendary bird, like a swallow but without feet, that never came out of the sky to roost. The ten spares sets were actually provided as finished aircraft; ten of the Martlet Is were lost when the freighter carrying them was torpedoed, and so the FAA received a total of 81. They were delivered with four 12.7-millimeter Browning guns in the wings.

The FAA had originally expected to obtain their G-36Bs with fixed wings, but Grumman was working on a wing-folding scheme at the time, which would allow a carrier to handle a substantially larger complement of aircraft. The British amended the contract to specify the folding wings, but the first ten of the order had already been built with fixed wings, arriving in the UK beginning in April 1941. Deliveries of the folding-wing G-36Bs began in August, with 36 shipped to Britain and 54 shipped to the Far East; they were designated "Martlet Mark II", with the ten fixed-wing aircraft then designated "Martlet Mark III".

The ten Martlet IIIs were apparently later refitted with folding wings; it is unclear if they were then redesignated Martlet Mark IIs. They are informally referred to here with the designation "Martlet III(A)" for convenience, since there would be another set of machines with a different configuration that were also known as Martlet IIIs. Nobody actually used the "(A)" suffix in practice, however.

* In the meantime, the Navy was concerned with engine development, worrying that the P&W R-1830-76 engine with a two-stage supercharger might run into development problems. Grumman built two "XF4F-5" test prototypes with the Wright R-1820-40 Cyclone radial as something of an "insurance policy"; the Navy also took out another "insurance policy" by ordering one more test prototype, the "XF4F-6", powered by a P&W R-1830-90 Twin Wasp with a single-stage two-speed supercharger. All three of these prototypes were evaluated in late 1940. Not surprisingly, the XF4F-6 suffered a loss of power at higher altitudes, but the Navy still ordered 95 of them under the designation of "F4F-3A". Except for the engine, the F4F-3A was effectively identical to the early production F4F-3, using the cowling with the air scoop and twin cowling flaps, and the cuffed Curtiss Electric propeller.

30 F4F-3As were to be provided to the Greeks and were being shipped when the Nazis overran Greece. They were taken over by the British in Gibraltar, to also be given the designation of "Martlet Mark III". They are informally referred to here as "Martlet Mark III(B)" to distinguish them from the fixed-wing G-36B Martlet Mark III(A) machines.

In summary, the tangle of deliveries of early mark Martlets ran like this:

The FAA would become an enthusiastic user of the Wildcat, with the type ultimately equipping a total of eleven squadrons.

BACK_TO_TOP* The folding wing used on the Martlet II had been in the works since March 1940, when the US Navy awarded Grumman a contract to modify the last production F4F-3 with folding wings. Designing the wings so they folded straight up would have been relatively straightforward, but that made demands on the height of carrier hangar decks, and so Grumman came up with an ingenious scheme in which the wings were folded back along the fuselage. The "span" of the folded wings was only 4.37 meters (14 feet 4 inches). According to company legend, the concept had been dreamed up by Leroy Grumman using a paperclip and a pink gum eraser.

The modified Wildcat, designated the "XF4F-4", performed its first flight on 14 April 1941, and was handed over to the Navy in May. It proved overweight, partly because it was fitted with a relatively cumbersome hydraulic wing-folding scheme. Grumman proposed a manual wing-folding scheme to cut weight, and the Navy authorized production of the variant with this feature as the "F4F-4", which reached line service after the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942.

The wing-folding mechanism was actuated by a crank inserted into a socket and turned by the deck crew team chief, with the rest of the team helping the wings along to folded position. Once folded, struts were attached between the wingtips and the tailplane to keep the wings in place. The F4F-4 also featured improvements as dictated by British combat experience, such as more armor and self-sealing tanks.

As per British requirements, it was fitted with six 12.7-millimeter Browning machine guns in the wings. Somewhat surprisingly, the increased armament was not popular with US Navy and Marine fliers, since the ammunition load was only 240 rounds per gun, resulting in a total ammunition load 360 rounds less than that of the F4F-3, which many felt was a bad trade. The two outboard guns could be fired separately from the four inboard guns, and many pilots would only use the four inboard guns, retaining the outboard guns as an emergency reserve.

Other changes included a modified pitot tube, moved from the leading edge of the wing to an L-style mount under the wing, and a simplified windscreen that eliminated a brace. The cowling was much like that of late production F4F-3s, with the eight rear cowling flaps, but an airscoop for the carburetor intake was mounted on the upper lip of the cowling.

Once in service, some ingenious mechanics improvised a mount on the centerline for a 159-liter (45 US gallon) external tank; a Grumman engineer named Carl Anderson came up with a better scheme, in which a 220-liter (58 US gallon) external tank was carried inboard on each wing on a somewhat cluttered bracket arrangement. The external tank scheme raised the weight of the aircraft, but the stretched range made it worthwhile. Anderson's scheme was incorporated into Wildcat production, and upgrade kits were provided for Wildcats already in service.

The USN obtained 1,169 F4F-4s. The FAA obtained 220 "Martlet IVs" that were based on the F4F-4 but had substantial differences, most particularly the fit of a Wright R-1820-40B Cyclone in a distinctly more rounded and compact cowling, with a single double-wide flap on each side of the rear and no lip intake. These machines were also referred to as "F4F-4Bs" for contractual purposes. At least one Martlet IV was modified by Blackburn Aircraft with six launch rails for "60-pounder" rockets, but the fit was not adopted operationally -- likely because the cluttered launch rails cut into performance too much.

___________________________________________________________________

GRUMMAN F4F-4 WILDCAT:

___________________________________________________________________

wingspan:

11.58 meters (38 feet)

wing area:

24.15 sq_meters (260 sq_feet)

length:

8.76 meters (28 feet 9 inches)

height:

2.81 meters (9 feet 2 inches)

empty weight:

2,610 kilograms (5,755 pounds)

max loaded weight:

3,610 kilograms (7,950 pounds)

maximum speed:

510 KPH (320 MPH / 280 KT)

service ceiling:

12,000 meters (39,400 feet)

range:

1,240 kilometers (770 MI / 670 NMI)

___________________________________________________________________

* The Wildcat was so important to the Allied war effort that General Motors (GM) was enlisted as a second-source. The war had idled five of GM's plants on the East Coast, and they were converted to aircraft production as the "Eastern Aircraft Division". A massive order for Wildcats was placed with Eastern Aircraft on 18 April 1942. The GM-built Wildcat was designated the "FM-1", and was similar to the F4F-2 but went back to the older armament configuration of four machine guns instead of six and a larger ammunition supply. Grumman hadn't really wanted the six-gun fit on the F4F-4 in the first place, but compatibility with British requirements had forced the company to comply. With new Wildcat production lines opening up, compatibility was no longer an issue, and so the old four-gun armament was reinstated.

The first FM-1 flew on 31 August 1942. 838 were supplied to the USN and 312 were supplied to the British. The Fleet Air Arm originally gave them the designation of "Martlet V", but in January 1944, realizing that maintaining a different name led to continuous small but obnoxious confusions, decided to adopt the American names for US-supplied aircraft and redesignated them as the "Wildcat V". The British objections to the four-gun armament were dropped -- though it is unclear if this was because the FAA had also decided that six-gun armament was a bad idea, or if the service was simply taking what it was offered.

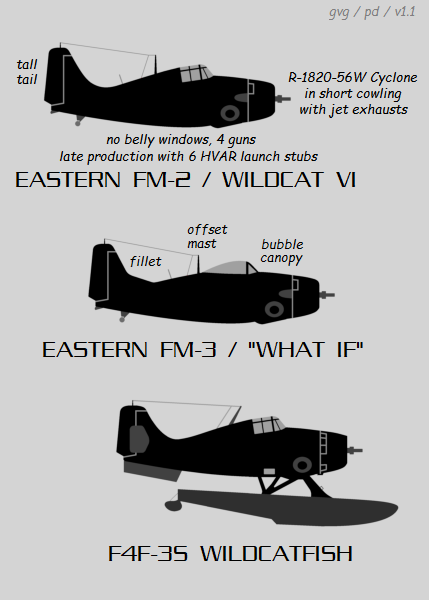

* As is typical with combat aircraft development, refinements of the Wildcat added weight, with its inevitable penalty on performance. To compensate, Grumman decided to fit the Wildcat with the Wright XR-1820-56 Cyclone radial engine with 1,010 kW (1,350 HP) and substantially reduced weight, driving an uncuffed Hamilton Standard propeller. The double exhaust stubs found on the bottom of the cowling on every earlier Wildcat were replaced by jet-style exhaust ports to provide incremental additional propulsion thrust; there were two ports on the bottom and one port on each side of the cowling. This prototype, designated the "XF4F-8", also had a lighter airframe.

Initial flight of the XF4F-8 was on 8 November 1942. The torque of the bigger engine affected handling, so a second prototype was built with a tailfin increased in height by 22 centimeters (8.5 inches). Both prototypes were initially fitted with double slotted flaps, but the old single flap proved more effective, and they were refitted with it.

The changes proved satisfactory, and so the type went into production at GM as the "FM-2" in mid-1943, when Grumman stopped building Wildcats. The FM-2 was fitted with a production R-1820-56W engine featuring water-methanol power boost and driving an uncuffed Curtiss Electric propeller; a gross weight of 3,600 kilograms (7,950 pounds); and a top speed of 535 KPH (330 MPH). The FM-2 wasn't much faster than its predecessors, but it had a much superior rate of climb and a higher ceiling, though since it used a single-stage supercharger its performance degraded seriously at high altitudes. It was also more agile and had longer range; pilots generally regarded it as a fairly peppy little aircraft. Other changes included elimination of the useless belly windows, and fit of a straight-up radio mast, instead of a forward-canted radio mast as fitted to earlier production Wildcat variants. The tall tailfin, lack of belly windows, and vertical radio mast made the FM-2 the easiest of all Wildcat variants to recognize.

The FM-2 became the most heavily produced Wildcat variant, with 4,407 going to the US Navy, plus 370 to the FAA as the "Wildcat VI". The total of FM-2s was actually greater than the total production of all other Wildcat variants combined: ironically, most Wildcats were not built by Grumman. The last 1,400 FM-2s were fitted with three "zero-length" launch stubs under each wing for High Velocity Aircraft Rockets (HVAR), allowing the FM-2 to carry six HVARs. The HVARs were unguided but could be targeted with relative accuracy using the gunsight and tracer fire. The 127-millimeter (5-inch) HVARs gave the FM-2 a hefty punch in the close-support role, as well as for attacks on submarines and other shipping.

BACK_TO_TOP* The Wildcat was in combat with the Axis well before America entered World War II. Two FAA Martlet Is claimed "first blood" with the type on 25 December 1940 with the reported destruction of a German Junkers Ju 88 fast bomber. The Ju 88 had been on a reconnaissance mission over the Royal Navy base at Scapa Flow, in the Orkney Islands in the North Sea.

The FAA took the Martlet on a combat carrier cruise for the first time in July 1941 on the HMS AUDACITY, to be followed by deployment on the HMS ARGUS in August 1941. Both the AUDACITY and the ARGUS were light "escort" carriers, to which the compact Martlet / Wildcat was ideally suited. The Martlets soon found themselves in combat with the German Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Kondor long-range anti-shipping bomber, claiming the destruction of one in September 1941. The AUDACITY was torpedoed and went to the bottom in December 1941, taking its Martlets with it.

In the meantime, the fixed-wing Martlet III(B)s that the British had taken over from the Greeks were fighting in North Africa from land bases. They were given an appropriate color scheme, unique among Wildcats, of light blue underneath and desert sand on top, in contrast to the general color scheme of maritime Martlets, consisting of two-tone gray on top and light blue on the bottom. Carrier-borne Martlets kept busy, protecting convoys across the Atlantic and to Murmansk in the Soviet north, and providing teeth for Royal Navy strike forces in the Atlantic and the Far East. In the spring of 1942, FAA Martlets supported the occupation of Madagascar under Operation IRONCLAD; and late in the year they also supported the American invasion of North Africa under Operation TORCH, flying in American markings to prevent "friendly fire" losses.

* US Navy Wildcats also participated in TORCH. America had entered the war on the morning of 7 December 1941, when the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) attacked Pearl Harbor, sinking or damaging a good portion of the US Navy's Pacific fleet at anchor. Significantly, by luck of the draw the USN's fleet carriers were at sea at the time and survived the attack. The US Navy and Marines had almost 250 Wildcats in service at that time, and the F4F was in combat with the Japanese from the outset.

On 4 December, Major Paul Putnam had led 12 Wildcats of US Marine Squadron VMF-211 to Wake Island; eight of these aircraft were destroyed by a surprise Japanese bombing raid on 7 December. The four that were left put up a fight that was only too characteristic of a "Wildcat": they claimed the destruction of a Japanese Mitsubishi G4M bomber on 8 December, and on 10 December Marine Captain Henry T. "Baron" Elrod claimed the destruction of two more. That night, the Japanese tried to land on Wake, only to run into stubborn resistance from shore batteries and the Wildcats that sent the invading force back to sea to reconsider their plans. The Wildcats harassed the invaders with machine guns and bombs, with Elrod scoring a direct hit on the destroyer KISARAGI, sinking it.

The Japanese decided to soften up Wake before trying to land again. On 12 December, a formation of G4Ms attacked again, with the last two flyable Wildcats harassing their attacks. On 22 December, the bombers came back with carrier-based fighter escorts -- the agile and well-armed Mitsubishi A6M Zero -- and though the Wildcats claimed a kill on a Zero, they were outclassed and both were destroyed. The Marine fliers fought on as infantry when the Japanese landed on 23 December. Elrod was killed throwing a grenade, and was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

* Although US Navy and Marine Wildcats had been initially painted in a cheery color scheme of bright yellow wings and aluminum fuselage, in the spring of 1941, well before Pearl Harbor, a more warlike overall gray scheme was applied. Soon the red "meatball" in the center of the US star insignia would be painted over in white lest it cause confusion with the Japanese "rising sun", and the red and white striping on the rudder was eliminated as well.

The Americans suffered setback after setback in the early months of the war for the Pacific. US Navy and Marine Wildcat pilots had a steep learning curve to climb in coping with the Imperial Japanese Navy's Zero fighter. The Zero was faster and much more agile than the Wildcat. The only performance advantage the Wildcat had over the Zero was that it could escape combat by going into a dive; more significantly, the Wildcat was very rugged, able to take at least ten times the punishment of lightly-built Zero and go on fighting.

The key to success against the formidable Zero was improved tactics. General Claire Chennault's American Volunteer Group, fighting the Japanese in China on behalf of the Chinese government and flying Curtiss P-40 Warhawks, had encountered the Zero and learned much about its capabilities. Chennault had sent reports back to the US on the enemy fighter, but they ended up mostly gathering dust. Lieutenant Commander John S. "Jimmy" Thach, commander of squadron VF-3 on board the carrier USS SARATOGA, had been one of the few to take them seriously, and concluded that the standard fighter tactics used by the US Navy and Marines were ineffective. Procedure was to fly Wildcats in tight groups of three, which limited the Wildcat's maneuverability and left it at a disadvantage against the Zero.

Thach played aerial "war games" using matchsticks on a table and came up with a new concept. Wildcats would fly in loose groups of four, organized as two pairs of fighters, with each pair flying in parallel. If one of the two Wildcats got a Zero on his tail, the Wildcats would break and cross each other's line of flight. That would hopefully distract the pilot of the Zero and disrupt his aim; more importantly, the Wildcats would then curve back to a nose-on course, and the Zero would find itself in a head-on confrontation with an aircraft that was more or less as well armed as the A6M but could take far more punishment -- a game the Japanese fighter was likely to lose.

Thach's pilots had experimented with the tactic in aerial exercises but the Navy, with traditional military conservatism, was reluctant to adopt the new approach. However, with a hot war on and American fliers pressed to the wall, the "Thach weave" would be used in action, proving as successful as expected, and was eventually adopted as doctrine. The trick was also adopted by other Allied air forces.

BACK_TO_TOP* By early 1942, the US Navy was taking the first baby steps towards bringing the war back to the Japanese, with carriers conducting raids against Japanese installations in the central Pacific. The raids were too small to inflict any real damage, but they could hopefully distract the Japanese, give experience in conducting more earnest operations later, and help keep up morale. At the beginning of February, planes from the carriers ENTERPRISE and YORKTOWN struck targets in the Japanese-held Marshall Islands. The ENTERPRISE lost 13 aircraft, though the USN also claimed destruction of five G4M bombers and a big Kawanishi H6K flying boat.

Later in the month, the carrier LEXINGTON attempted to launch a strike on Rabaul, the Japanese stronghold far to the south on the island of New Britain. The Japanese discovered the carrier group before the strike could be launched, forcing cancellation of the attack, but in air battles with Japanese aircraft on 20 February 1942, the Wildcats claimed a good number of kills. Jimmy Thach and his crew were on the LEXINGTON, the SARATOGA being laid up for repairs after being torpedoed on 11 January; his and five other Wildcats in his group shot down a Kawanishi H6K flying boat and claimed destruction of seven twin-engine Mitsubishi G4M bombers out of a flight of nine, with another intruder shot down by the LEXINGTON's anti-aircraft guns.

During the fighting, another group of four Wildcats, under Lieutenant Edward "Butch" O'Hare, intercepted another group of nine G4Ms. In a wild fight, O'Hare shot down five, and his wingmen claimed three more. Only two Wildcats were lost in the fighting that day, with one pilot killed. The G4M was a notoriously vulnerable aircraft; Jimmy Thach later calculated that O'Hare had only used 60 rounds to kill each bomber. The photogenic O'Hare, the Navy's very first air ace, was played up as a hero in the press, and awarded the Medal of Honor. After a stateside tour, O'Hare would return to air combat in late 1943, scoring two more kills, to be then be killed himself in confused circumstances during a night action. The city of Chicago would name its airport after him.

* These and other pinprick raids did little to slow down the Japanese steamroller as it swept over the South Pacific to threaten Australia. The first real confrontation between the carrier forces of the IJN and the USN took place on 7:8 May 1942, when a Japanese invasion fleet headed for Port Moresby in southern New Guinea was confronted by a US Navy carrier task force built around the LEXINGTON and YORKTOWN. The Americans had cracked Japanese codes and were ready; they drew first blood, sinking the light carrier SHOUHOU, resulting in the widely-publicized radio report: "Scratch one flattop!"

However, in the wild fighting that followed, the LEXINGTON was sunk and the YORKTOWN lightly damaged. The IJN carrier SHOUKAKU was hit but would be quickly repaired. Wildcats were in the thick of the fighting, taking losses and claiming kills. In the end, the US Navy had got the worst of it in the Battle of the Coral Sea. On the positive side, the Navy had halted the Japanese drive on Port Moresby, and more significantly, the US Navy had for the first time slugged it out head-on with the IJN, both taking and handing out punishment, which did much to improve morale for further confrontations. The next one would be the real test.

* In late May, an IJN carrier task force steamed to attack Midway Island, in hopes of luring the US Navy's carriers into a "decisive battle" that would settle the issue between the two navies. American codebreakers were well ahead of the Japanese plans, and again the US Navy was ready, spotting the Japanese fleet on 4 June 1942. There were air battles all day, with aircraft from the ENTERPRISE, YORKTOWN, HORNET, and Midway itself suffering until mid-morning, when the Japanese, confused by the continuous action and a futile torpedo-bombing attack by antiquated Douglas Devastator torpedo bombers, were caught flat-footed by Douglas Dauntless dive bombers that screamed down on the carriers KAGA, AKAGI, and SOURYUU. The three vessels were all cluttered with aircraft being loaded up with munitions for an attack, and they were shattered by secondary explosions. All three would sink, leaving only the HIRYUU unscathed.

While the dive bombers scored hits, the Wildcats above them tangled with Zeroes. Jimmy Thach and five of his wingmen were in the thick of it, using the Thach weave with good effect. A Zero got on the tail of Ensign Robert Dibb; Dibb led his pursuer around in a weave to a head-on attack by Thach, who, as he reported later, waited until the Zero "got fairly close, and we both opened up together, almost colliding. In the nick of time, he lifted his left wing and just slid over one side of my fuselage. I got a glance at the belly of his plane, and it was smoking, with red flames coming out. He'd missed me." Thach lost one of his pilots, but claimed destruction of six Zeroes.

The fighting continued through the day. Aircraft from the HIRYUU swept down on the YORKTOWN in mid-afternoon, and though Wildcats shot down half of the attackers a few got through, badly damaging the vessel. Dauntlesses had their revenge late that afternoon, pounding the HIRYUU, which would also go to the bottom. All the Japanese carriers in the attack fleet had been lost, and the operation was called off in the dark hours of the next morning. The US Navy harassed the fleeing Japanese the next day, hitting the heavy cruiser MOGAMI and sinking the heavy cruiser MIKUMA before the Japanese fleet was able to make its escape.

The YORKTOWN appeared likely to survive, but the carrier was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine on the afternoon of 5 June, and went down on the morning of 7 June. It was a painful loss; the only other American ship that went down was a destroyer that was hit by a torpedo in the same attack. Overall, however, the Battle of Midway was the greatest upset victory in American naval history, with a US Navy task force centered around three carriers confronting a Japanese task force built around four, and sinking all the enemy carriers though a combination of good intelligence, skill, courage, and sheer luck.

The Wildcats had held their own in the fight, with several aces emerging from the battle, but Navy and Marine pilots in Brewster Buffalos were simply massacred. The Buffalo was quickly pulled from first-line service. The real hero of the action was the Dauntless, an aircraft that in retrospect was on the edge of outdated, but which had tipped the naval battle in the Pacific in favor of the Americans.

* The Americans took the initiative within a month, landing a force of Marines on Guadalcanal, at the southeast end of the Solomons island chain in the South Pacific, on 7 August 1942 under Operation WATCHTOWER. The Japanese had been building an airstrip there, which would have allowed them to intercept Allied shipping to Australia. The Marines quickly captured the airstrip, which was named Henderson Field.

The landing on Guadalcanal led to a wild sequence of vicious land and sea battles for the rest of the year. The Japanese were at a disadvantage, since Guadalcanal was distant from their main base at Rabaul, giving them a long supply line that would prove painfully vulnerable to attack, as well as stretching the range of their ground-based aircraft to the limit.

The Japanese were almost always aggressive, however, and were quick to contest the landing with air power. There were three days of furious air battles starting the day of the landing. Wildcats put up a stiff fight. The Thach weave proved effective, since most of the Japanese pilots weren't wise to the trick and didn't see the "sucker punch" coming; the Japanese found that the Wildcat could take an extraordinary beating and still keep fighting; and they discovered that there were some outstanding pilots among the Americans.

Famed Japanese ace Sakai Saburou was astounded by one dogfight: "A single Wildcat pursued three Zero fighters, firing in short bursts at the frantic Japanese planes. All four planes were in a wild dogfight, flying tight left spirals. The Zeros should have been able to take the lone Grumman without any trouble, but every time a Zero caught the Wildcat before its guns, the enemy plane flipped away wildly and came out again on the tail of a Zero. I had never seen such flying before." Given that the Wildcat's agility was unarguably inferior to that of a Zero, the pilot must have been extraordinarily skillful. The three days of air fighting cost the Americans 11 Wildcats plus a Dauntless, while the Japanese lost 42 planes -- many of them simply because they ran out of fuel on the way back to Rabaul.

The Americans were badly pressed at first, but the Marines had an ace in the hole, an "unsinkable aircraft carrier" in the form of Henderson Field, which was completed in mid-August. It wasn't much to look at, being "a bowl of black dust or a quagmire of mud", but although the Japanese repeatedly tried to knock it out, they never quite succeeded. Marine Wildcat pilots flying from the field contested Japanese air attacks and, in cooperation with US Army Bell Airacobras, performed attacks on Japanese vessels and troop concentrations. Since Guadalcanal was codenamed "Cactus", the flight contingent there was known as the "Cactus Air Force". The Cactus Air Force suffered a long seesaw battle of its own -- gradually suffering cycles of attrition, only to be relieved by new infusions of pilots and aircraft at the eleventh hour.

Guadalcanal would produce the top three Wildcat aces. Captain Joe Foss, later governor of South Dakota, would take first place, with a total of 26 kills. Major John L. Smith was second place, credited with a total of 19 kills; Captain Marion Carl was third, credited with a total of 18, including two kills at Midway and two kills later in the war in a Vought Corsair. Foss and Smith would win the Medal of Honor; Carl would become a famous test pilot after the war.

Over the months of fighting, the Americans were able to pour resources into the fight at an increasing rate, while the overstretched Japanese attempts to retake the island gradually ground down in blood, mud, and exhaustion. In December 1942, the Japanese high command gave up on the battle, and the survivors of the Imperial Japanese Army force on Guadalcanal were withdrawn in early 1943.

* By that time, the Wildcat was beginning to be replaced by the Grumman F6F Hellcat, basically a "bigger and badder" Wildcat, built along much the same lines but with better performance, more armament, and a more reasonable landing gear arrangement. It was a welcome improvement: Wildcat pilots were painfully aware of the type's limitations, with Jimmy Thach saying later that its successes against the Zero were mainly due to poor marksmanship and "stupid mistakes" on the part of the enemy, and good piloting skills plus teamwork on the part of the Americans. Oddly enough, Japanese pilots were very highly trained, put through a harsh physical regimen reminiscent of commando training, but their training doctrines were not as effective as expected. The excessively high standards of Japanese pilot training also limited their ability to "produce" pilots, which would become a critical weakness later.

By mid-1943, the Hellcat had completely replaced the Wildcat in first-line fighter service, but the F4F remained an important asset, flying off small escort or "jeep" carriers to protect convoys from anti-shipping aircraft, help pin down enemy submarines, or support amphibious operations. Wildcats operating on antisubmarine patrol in the Atlantic were generally painted in a neat color scheme, featuring white on the bottom and a light "gull gray" on top. Late in the war, US Navy and Marine Wildcats sported a tidy overall dark blue color scheme.

Although these might have been "second string" duties, the Wildcat still kept busy up to the end, scoring hundreds more aerial victories. In February 1945, FAA Wildcats flying off the HMS VINDEX in support of a Murmansk convoy shot down three Ju 88s, and on 25 March 1945 Wildcats of FAA Squadron Number 882 got into a tangle with German Bf 109Gs off of Norway and shot down four of them. This was said to have been the last air-to-air combat of FAA Wildcats. Rocket-armed FM-2s provided valuable close support during the invasions of the Philippines and Okinawa. One Wildcat claimed destruction of a Japanese Yokosuka P1Y bomber on 5 August 1945, the type's last "kill" of the war.

Wildcat production ceased in May 1945, when the war in the Europe ended. It was in the twilight of its career at that time and its service life was very short in the postwar period. Unlike other famous World War II warbirds, the F4F did not have a significant postwar career in the air forces or navies of smaller nations. There is a tale that, following the war, Grumman flew a Wildcat as an "executive transport", with two passenger seats below and behind the cockpit, plus two windows on each side. One suspects it was cramped. Many Wildcats survive as static displays and a number, mostly FM-2s, remain airworthy as airshow "warbirds".

BACK_TO_TOP* A number of special Wildcat variants were built. In the fall of 1942, one F4F-3 was converted to a floatplane configuration, using twin Edo floats. The landing gear sockets were faired over, the tailwheel was deleted, and small vertical finlets were added to improve yaw stability; a ventral fin was also added after early trials. The conversion was at least informally known as the "F4F-3S Wildcatfish" and performed its first flight on 28 February 1943, with Grumman test pilot F. Hank Kurt at the controls.

The motivation behind the scheme was that the Japanese had introduced a float version of the Zero, the Nakajima A6M2-N, and that a floatplane fighter would be able to operate out of protected harbors where airstrips were not available. However, the Wildcat was never noted for blazing performance, and the floats drastically cut the aircraft's speed. In addition, US Navy Construction Battalions ("CBs" or "SeaBees") proved highly competent at carving out airstrips under the worst conditions in a short period of time. Although a batch of 100 Wildcatfish had been ordered, the order was canceled and the aircraft were built as conventional F4F-3s.

At least ten F4F-3s were field-converted to a reconnaissance specification by installing a vertical camera in the rear fuselage. The fits tended to vary, but all these machines retained armament; they were designated "F4F-3P". Of course, a number of F4F-4s were similarly modified and designated as "F4F-4P". Reconnaissance Wildcats served in the South Pacific and in the invasion of North Africa.

In early 1941, Grumman began work on an ultra-long-range photo-reconnaissance version of the Wildcat. An F4F-4 was extensively modified to this configuration, with nonfolding "wet" wings and distinctive twin "tailpipes" that were actually used for dumping excess fuel to lighten the aircraft for carrier deck landings. A single camera was installed behind the cockpit, an autopilot was fitted for long missions, and the armament and gunsight were deleted. The first such "F4F-7" performed its first flight on 30 December 1941.

The F4F-7 could carry a load of 2,596 liters (685 US gallons) of fuel, giving it a range of 5,950 kilometers (3,700 miles). A hundred were ordered but only 21 were delivered. In 1942, one flew across the US, coast to coast nonstop, in eleven hours. When the flight plan was filed, an Army air traffic controller called the Navy and said it looked as though there was a mistake. A Navy man replied: "The flight plan is correct. All Navy fighters have a 3,000-mile range." It was a record flight, but the F4F-7 was a secret, and so the record wasn't claimed.

The F4F-7s served in the Solomons, but the actual need for an extremely long range reconnaissance fighter was slight. Those F4F-7s that were delivered were used for spares hulks, with some possibly modified back to a fighter specification.

There were trials in which Wildcats were towed by bombers such as the B-17 to give them longer range. These experiments were said to have worked out fairly well from a technical point of view, but the scheme did not go into service.

* The following list summarizes Wildcat production:

That gave total production of F4Fs (as such) of 1,602 aircraft.

That gave total Eastern Wildcat production of 5,928 aircraft.

That gave total Martlet production as 531 aircraft, for 8,061 Wildcats built in all.

BACK_TO_TOP* There were, as always, a number of small discrepancies between sources concerning the Wildcat. For example, some said Wildcat production ended in August 1945, though it seems hard enough to believe that it lasted as long as May 1945 since the type was clearly on the way out even then. Apparently quite a few of them were simply dumped in the drink at the end of the war.

I got to chatting with a UK correspondent who liked the Wildcat and speculated about improvements such as a bubble canopy. The idea appealed to me; since the Wildcat stayed in production so long, a final make-over in its twilight days seemed plausible enough. I drew up an illustration of the imaginary "FM-3 / Wildcat VII / Super Wildcat", adding a fin fillet since fitting the bubble canopy to other American fighters like the Mustang and Thunderbolt created yaw instability that led to fit of a fillet on those aircraft.

He also suggested that the landing gear be provided with electric drive -- yeah, OK -- or that the aircraft be redesigned with a more adequate landing gear scheme. I balked at that; it was too much like reinventing the Hellcat. The bubble canopy was pushing it enough, though it didn't seem to have been too difficult to fit it to the Mustang and Thunderbolt. Whether anyone ever actually thought of building such a machine is another good question.

* Sources include:

* Illustrations credits:

* Revision history:

v1.0.0 / 01 oct 04 v1.0.1 / 01 nov 04 / Added HORNET to battle of Midway. v1.0.2 / 01 nov 06 / Review & polish. v1.0.3 / 01 jul 07 / Added "Super Wildcat". v1.0.4 / 01 jun 09 / Review & polish. v1.0.5 / 01 apr 11 / Review & polish. v1.0.6 / 01 mar 13 / Review & polish. v1.0.7 / 01 feb 15 / Review & polish. v1.0.8 / 01 jan 17 / Review & polish. v1.0.9 / 01 dec 18 / Review & polish. v1.1.0 / 01 jan 20 / Illustrations update. v1.1.1 / 01 jan 23 / Review & polish. v1.1.2 / 01 jan 25 / Review & polish. (*)BACK_TO_TOP